The only biography of Johns Hopkins is Johns Hopkins: A Silhouette, a 125-page profile written in 1929 by his grandniece Helen Hopkins Thom. No biography of more length and depth has ever been written because Hopkins destroyed most of his personal papers. Yet one fascinating clue to Hopkins' personality—and influence—can be found in the Library of Congress' online collection of Abraham Lincoln's correspondence. It is a letter from Hopkins to Lincoln offering some advice in 1862.

Baltimore, home to many Southern sympathizers, had been the site of the Civil War's first bloodshed. On April 19, 1861, a week after South Carolinian forces had fired upon Charleston's Fort Sumter, starting the war but inflicting no casualties, a large brick-throwing and gun-toting Baltimore mob had attacked federal troops passing through town. Four soldiers and 12 civilians were killed and dozens wounded. Lincoln put Baltimore under military control and in June 1862, Maj. Gen. John E. Wool became commander of the Department of Maryland, and thus de facto commander of Baltimore.

Wool was a tough customer. A veteran of the War of 1812, he was 78 years old—the oldest commander in active service on either side of the Civil War. In October 1862, he learned of a petition by supposed pro-Unionists who charged that he was incompetent and possibly senile. The petition urged Lincoln to replace him. On October 27, 1862, Wool ordered the arrest of everyone who had signed it.

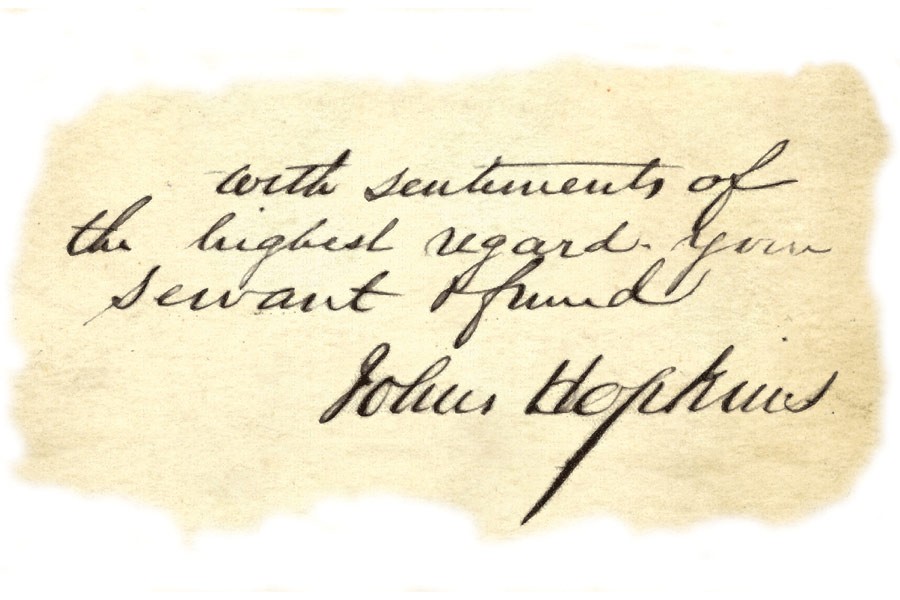

Hopkins believed that Wool merited support. On October 30, 1862, he took a piece of plain, lined note paper and wrote to Lincoln:

Sir, When I had last the pleasure of seeing you, I press'd on you the importance of retaining Genl Wool in his present position here, looking to the preservation of the peace of the city, and the cause of the Union.

Present events which have renewed the efforts of certain parties to remove him, only confirm me in my former convictions; and my object in now addressing you is to throw what weight I can into the scale in favour of his being retained—I am of the opinion that no one whom you could put in his place, could better serve the purposes of the government, in a city whose peace and tranquility at this time are in great measure owing to his judgement and discretion.

With sentiments of the highest regard—your Servant & friend

Johns Hopkins

The letter provides tantalizing hints about Hopkins' relationship to Lincoln. Clearly they had met previously—Hopkins wrote, "when I had last the pleasure of seeing you" (emphasis added). It also shows that Hopkins was not only a firm supporter of the Union [1] but an admirer of Lincoln, signing the letter "your Servant & friend."

Hopkins, indeed, was staunchly pro-Union in a city that had a large pro-Confederate population. He and his good friend John Work Garrett, president of the B&O Railroad, overcame the opposition of pro-Southern members of the railroad's board to ensure that B&O trains and tracks served the Union cause.

Lincoln followed Hopkins' advice on Wool—briefly. In December 1862, he replaced Wool but did not fire him. Instead, he transferred the old warrior to the command of New York City. In July 1863, the septuagenarian Wool commanded federal forces that responded to the racially charged, three-day anti-draft riots there. At least 120 were killed. Within weeks of that riot, Wool retired from the Army—apparently not voluntarily. He did not have the equivalent of Johns Hopkins in New York to urge Lincoln to keep him on.

[1] Previously adopted accounts portray Johns Hopkins as an early abolitionist whose father had freed the family's enslaved people in the early 1800s, but recently discovered records offer strong evidence that Johns Hopkins held enslaved people in his home until at least the mid-1800s. Additional information about the university's investigation of this history is available on the Hopkins Retrospective website.

Posted in Politics+Society