Midafternoon, mid-December at the Johns Hopkins varsity pool and George Kennedy Jr. watches a swimmer cleave the water of Lane 1. Kennedy is head coach of the men's and women's swim teams at Hopkins. The swimmer is Taylor Kitayama, a 5-foot-3 powerhouse sprinter who has won Kennedy's respect and affection by coming to the pool every day with purpose and focus on every detail of the day's workout. That focus has paid off. At this point in the 2012-13 season, she has swum the 100- and 200-yard backstroke and 100-yard butterfly faster than anyone else on the women's team. At a November meet alliteratively named the Gettysburg Final Fall Fast Festival, Kitayama set five pool records. As a sophomore at last year's NCAA national championships, she placed eighth in the 100 back and ninth in the 200 back. Her first two years on the team, she was All-American, and she has already qualified for this year's NCAA nationals.

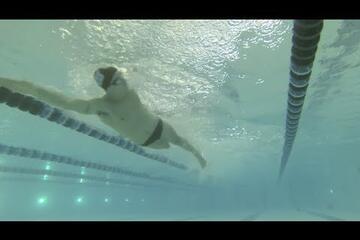

Kennedy watches her complete a lap of the pool, make the turn, and resume her stroke with grace and precision and power—"she moves a lot of water" in the coach's parlance. He nods his head toward me and then toward the pool and rises on his toes, arms stretched overhead, to make a point. "A really good swimmer looks connected from fingertips to toes," he says, and that well describes Kitayama. Aquatic verbs and adjectives apply: She flows through the water with a fluid stroke and though her arms and legs generate tremendous power there is a liquid quality to her limbs. Fast swimmers are compared to dolphins for good reason.

Though dolphins do not have to think to swim fast. Humans do. During a race, thinking most likely will ruin any chance of winning. But in training, there is much to think about. Off the starting block are you entering the water at the optimal angle and sliding through the smallest possible hole? Is your stroke efficient or are you beginning to spin your arms faster with no gain in speed? Is your shoulder rotation proper? What is the position of your hand as you pull back through the water? Are you breathing into the turn or right out of the turn? The former will slow you down. Does your kick take advantage of your flexible ankles and hyperextended knees, if you have been blessed with both?

As he paces the pool deck Kennedy keeps an eye on the other swimmers, too. They are in the water for their second workout of the day. The first had taken place at 6:30 in the morning. From time to time Kennedy calls out instructions or observations, and he has to shout to be heard over the sound of churning water and the pulsating music that pounds through a poolside loudspeaker. Kennedy is tall and lean and loose- limbed, typically dressed for work in jeans or shorts and a faded shirt. Too many hours at outdoor pools and not enough sunblock have left their mark on his scalp; he has been treated several times for skin cancer. That does not seem to bother him, but then little seems to bother him. Varsity collegiate coaching in all sports often seems populated by tense, driven, humorless men and women with clenched jaws and glaring eyes and belligerent voices. That does not describe Kennedy, who at any hour of the day is unrelentingly cheerful and good-humored. He conveys the impression of a man who cannot think of anything he would rather do than coach swimmers, which is pretty much how he feels.

He has been coaching them at Johns Hopkins for 28 seasons. When he coaches a meet at the Hopkins pool, the score is kept on the Coach George Kennedy Scoreboard. The school named it after him in 2010. On the wall outside his cramped poolside office there is a plaque dedicated to his late father, George Kennedy Sr., "Loyal Fan of Johns Hopkins Swimming." The plaque was given to him by his swimmers. The athletic department mounted it on the wall. Such markers of respect and esteem derive from his results in the pool. Thirty-nine of his men's and women's teams have finished the NCAA national championships in the top 10; 14 of those finished in the top five. He has produced 12 individual NCAA champions, and three times his men's teams have finished second in the nation. Six times he has been NCAA Division III national coach of the year. For a month last fall, both the Hopkins men's and women's teams were ranked No. 1 in the country, and they have remained in the top five all season.

Kennedy's swimmers follow detailed and color-coded training schedules that change every day and are based on continuous monitoring of the latest sports training research, what other programs are doing, and new ideas discussed on Internet swim sites and discussion boards. Kennedy and his assistant, Nikki Kett, gather data on lap times and stroke rates and race tempos, and forward those data to the swimmers. To swim fast requires strength and endurance, strong muscles and hearts and lungs. But Kennedy will tell you that what matters more is what is in the the athletes' heads. Were he to name his method that name could be Head First. Essential to turning a talented high school kid into a fast collegiate swimmer is convincing him or her to believe in Kennedy's method. Follow the program and listen to the coaches and you will go faster. "To me, the whole person steps up to race," he says. "I think the emotional part might be the most important thing. If someone really thinks they're going to go fast, 90 percent of the time they will."

Nikki Kett is in her first year as Kennedy's assistant coach. An All-American swimmer when she was at Kenyon College in Ohio, she now works from a closet-sized office stuffed with technology. Outside her window, the day's practice is under way and a junior freestyler named Sarah Rinsma, who finished fourth in the 200-yard free at the 2012 NCAA nationals, is swimming in Lane 4. She is the Jays' fastest in that event despite what Kett describes as a stroke that could be more efficient. Kett demonstrates how Rinsma's hand enters the water in line with her head instead of in line with her shoulder. "You want to enter with a high elbow in front of your shoulder and pull straight back," she explains. She cues up video of Rinsma, shot underwater by a teammate who was on the bottom of the pool holding her breath. "See how her right hand sculls out every time?" Kett asks. "She's wasting a lot of time doing that and not catching as much water as she could." In practice when she can slow down and concentrate on her stroke, Kett says, Rinsma does better. When she moves up to race pace, the bad habit tends to creep back in.

Swimmers sign up to have teammates film their strokes or their turns or their starts, as a training aid. When they see errors, they work on them in practice. Eleanor Gardner is a senior freestyler from Bermuda who says her stroke tends to be too short, with not enough shoulder rotation. The insufficient rotation in her shoulder is what shortens her stroke. On request she demonstrates: "First your elbow begins catching water as your arm enters and pulls back. Your elbow and your shoulder and your forearm and your hand all need to catch water or you will not be fast enough." That makes it sound simple but it is not, as any of the swimmers is quick to note. Carter Gisriel is swimming his last season for Hopkins. Kennedy likes to call the 5-foot-8, 150-pound senior sprinter Pound for Pound, "because pound for pound he's the best swimmer on the team." Says Gisriel, "You're swimming 6,000 yards per practice—doing something for 6,000 yards—and at the end they say, 'You're doing that wrong.' As soon as you try to change it, your stroke feels totally weird." The trick is to so integrate what feels totally weird in practice that you can do it in a race without having to think about it. A thinking racer is a slow racer.

Kett gathers data from each race meet and from practice and posts it to a Johns Hopkins swim team Google Group so the athletes can analyze it. She will time each swimmer's stroke cycle to determine the tempo, which is the number of seconds it takes the swimmer to make a designated number of strokes (in the case of freestyle, for example, five strokes with each arm). Tempo is an important measure of efficiency. Kett shows me data from one practice that she posted for Hannah Benn, a sophomore freestyler and backstroker. As instructed by the day's workout sheet, Benn had swum a lap at 90 percent of race pace, and another lap at 95 percent. She took 11.53 seconds to swim the 90 percent lap, but 11.69 seconds for the 95 percent lap, which meant she had swum slower when working harder, which would seem not to make sense. A second set of numbers—Benn's tempo—tells the story of why. On the faster lap, she had taken 5.1 seconds for a cycle of five strokes; on the slower lap, 4.8 seconds. That is counterintuitive, but the thing to understand is that a faster stroke cycle is not an indication of speed, but of inefficiency, which produced Benn's slower lap. "They don't ever think that way," Kett says of the swimmers. "They think, 'If I try harder, I'll go faster.' It's good for them to see the data."

"A Hopkins swimmer really relates to anything that is scientific," Kennedy says. There is a preponderance of rigorous technical majors on both the men's and women's teams—chemical engineering, behaviorial biology, neuroscience. Of the 37 varsity swimmers this year with declared majors, 31 are in either engineering or science. Gardner will be a Rhodes scholar next year. She grins and says, "We have a very smart team." Kennedy likes to tell the story of his first encounter with their braininess, and their cockiness. The day before his first competition as head coach in 1985, an away meet at Washington and Lee University, he wanted to impress his new team with how organized he was. So he posted on the team bulletin board a detailed itinerary. "I came in the next day and the whole thing had been edited in red ink."

Swimmers look ultrafit, with little discernible body fat and strikingly broad and full shoulders and upper backs. But they do not have the bulky musculature of a wrestler or football player, bodies that say really really strong. Nevertheless, once they start grinding through sets of presses, squats, curls, and pull-ups in a predawn workout in the varsity weight room, it is apparent how strong they are. The exertion required to maintain that strength requires a lot of calories, and Kennedy can tell stories about how much they eat. Each year the team takes a January trip to train and compete in Florida. Last year they came upon a McDonald's that offered a special—buy one Big Mac, get another for a penny. That day, 20 swimmers consumed 119 Big Macs, stacking the boxes in a pyramid for a photo posted on Facebook. The champ was breaststroker Gideon Hou, who put away nine and a half. "Yeah," Hou says. "It was pretty gross."

Kennedy plugs in the music, hands out individualized weight routines, and watches them work, encouraging this one, teasing that one, asking a third if he's feeling better than he has the last few days. That Kennedy now makes his living coaching swimmers owes something to his older sister's collarbone. There were four Kennedy kids growing up in Moorestown, New Jersey, three girls and George Jr., and their parents had been physical education majors at Ursinus College, so the family was active. When Kennedy's sister broke her clavicle playing tackle football as a 6-year-old, a doctor prescribed swimming to rehabilitate the injury, which led to the Kennedy brood joining a summer swim team. Young George, age 5, loved everything about it—the water, the games, the other kids at the small-town pool. He began racing the next year and by high school was good enough to earn a spot on a varsity squad that won three state championships in his four years. He swam on some of the champion relay teams, and though he says his best times would not be good enough for him to swim for Johns Hopkins now, they were good enough then to earn a partial scholarship at the University of North Carolina. He began as a history major but switched to physical education when he got the idea of someday becoming a swim coach.

At 25, after earning a master's degree in education, he became head coach at Gettysburg College. His responsibilities included teaching several phys ed classes and managing the school's six-lane bowling alley, which was located one floor beneath the pool. "I'm the least mechanical person you would ever want to meet. The other phys ed instructors would come up to my office at the pool and say, 'Lane 4 is down.' I'd go down and act like I was fixing it. Before you knew it, there'd be four or five more lanes down. Eventually they took that part of the job away from me."

No record exists of the long-ago day when someone first figured out, maybe from observing animals, that a human could move arms and legs in the water so as not to drown. But swimming appears in The Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, and Beowulf. In 1595, Christofer Middleton noted in his book A Short Introduction for to Learne to Swimme that a man could swim on his back, "a gift which thee hath denied even to the watrie inhabitants of the sea," and recommended that he learn this "after he hath learned to perfectly swim to and fro on his bellie." A translation of M. Thévenot's The Art of Swimming, Illustrated by Proper Figures with Advice for Bathing appeared in London in 1699, and offered, "It must be acknowledged that the Art of Swimming may be of no small Importance to the greatest Personages and most elevated conditions of life."

There is also no record of the day when someone, great Personage or not, first hit on the idea that not only could you swim to and fro on bellie or back, you could race. There is record of a 40-yard racing exhibition in 1844 between British swimmers and a pair of North American Ojibwa Indians, in which Europe may have gotten its first look at the competitive stroke we now call freestyle. The British, who employed the breaststroke, were unimpressed by the Indians' method, which one observer dismissed as "grotesque antics" and the April 22 edition of The London Times called "un-European." This may have been sour grapes because in the race, according to eyewitness accounts, the un-European Ojibwas smoked the Brits.

Racing, whenever it began, begat the need for learning how to swim faster. There is now a voluminous literature on how to train swimmers, as well as a long list of websites and uncounted YouTube videos of various techniques. The Journal of Swimming Research publishes articles like "Asymmetries in Swimming: Where Do They Come From?" and "The Effect of Intermittent Hypoxic Exposure Plus Sea Level Swimming Training on Anaerobic Swimming Performance." Kennedy likes to downplay his intellectual capabilities compared to the students he coaches, but he studies the sport constantly and can speak fluently about the best way to build aerobic base, or the emphasis in the last 10 years on improving the kick, and explain, "If they're taking 10 strokes per length and they're up to a really good tempo, the combination of distance-per-stroke times the stroke rate is what's going to give them velocity in the water."

Johns Hopkins swimmers learn that one constant of their coach is his willingness to try anything new that might make them faster. "I'm 57 years old, and the athletes are 18, 19, 20, so there's a natural disconnect," Kennedy says. "If we coach by doing the same stuff all the time, they'll start to question, because there are new things going on all the time." The swimmers quickly learn that nothing they do is exempt from his tinkering. Kennedy has a sort of motto: "If it's not broken, break it anyhow to go from good to great." Kitayama says this can take getting used to. "If something works, I don't want to change it, even if I know that I can be better," she says. "What has gotten me through all the changes is knowing that, when it comes right down to it, Coach really does know what he's doing."

At 6:15 a.m., bleary and yawning young men and women mill at the start end of the pool, adjusting their swim caps and goggles with perhaps a little extra care because no one is eager to make that cold plunge into the water. Finally they start diving into the pool. One woman yelps when a teammate splashes her. Kennedy observes them and chuckles. "The boys always warm up on one side of the pool and the girls on the other. It's like an eighth-grade dance." On a Monday, he can pick out who had a long and lively weekend by how they look in the water—"lethargic, like they've got mono."

Much of the time he observes in silence. He's not much of a shouter. "I don't have to worry too much about the women," he says. "It's the guys. I don't like to yell, but I've learned that if I give the guys a little tough love once in a while, they tend to understand that." Workouts are meticulously planned and if Kennedy spots the swimmers not doing something precisely right, he will make them start the sequence over, no matter how deep into it they might be. He has a knack, the swimmers say, for figuring out how best to spur each one. "He can press my buttons and know he can get away with it and make me swim faster," Gisriel says. "Since I've been at Hopkins I've dropped 1.3 seconds in the 50, which is like four body lengths, which is absurd. In the 100 fly I've dropped 3 and a half seconds, which is, again, absurd. That's unheard of. If you trust what he has planned for you, you'll do well. I've trusted him from day one." Says Kennedy, "Our job is to help them find a way to be successful. If we can find that, they start believing in everything they do."

On this morning, the teams are working with various pieces of apparatus. For designated laps some float on kickboards and propel themselves only by their legs, working on their kicks. Other laps they wear mesh bags that strap to their ankles and force them to work against increased drag. In one regimen, a swimmer wears a belt attached to a long elastic cord, like a bungee cord, while a teammate stands on the pool deck and holds the other end, forcing the swimmer to work against resistance as the cord stretches out. On the return lap, the teammate on deck pulls the cord in as fast as possible. The magnified speed makes even small bad habits apparent to the swimmer. "You can feel every little thing that you're doing wrong," Gisriel says.

Intercollegiate swimming is a team sport, but the goal each season is not to win all the racing meets. The goal is to qualify as many swimmers as possible for the season-ending conference and NCAA championships. Entire teams do not earn invitations to the national championship as in, say, basketball or lacrosse. Instead, individual swimmers qualify by posting race times through the season that meet the qualification standards. So regular season meets serve in effect as NCAA qualification heats and one more form of race training. (They are also fun. Racers like to race.) "The end-of-year championship planning really begins the first day of practice," Kennedy says. Twelve men and 11 women from this season's teams have made the 2013 NCAA grade, which means he expects Hopkins to make another strong showing at nationals in late March.

That means week by week the pressure builds on athletes already enduring the pressures of being Johns Hopkins undergraduates. Kennedy frequently encounters the high expectations of kids who are used to life as overachieving fast learners. "Skill acquisition means repetition and repetition and repetition and repetition," he says. "It depends on everyone's patience. Hopkins kids want to be good yesterday." He and Kett try to check in with each swimmer individually at least every other day. "I'll ask, 'How you doing?'" Kennedy says. "'Oh, I'm fine.' 'OK. How you really doing?' And then sometimes you see the tears coming up." When he spots a kid who is starting to look physically and emotionally spent, he will pull him or her aside and grant a day off. "Sometimes I question my own sanity," Gardner says. "Why do I enjoy this so much? But I've been swimming since I was 6. I don't think I know how to live without that kind of physical release. It's really exciting to see how far you can push yourself."

As a varsity swimmer at North Carolina, Kennedy ate his meals at the athletes' training table and observed that when the Carolina football team won, the players got steak and lobster for dinner. If they lost, they came into the dining hall and found plates with a single slice of bologna and a single slice of cheese. So before that first competition at Washington and Lee 28 years ago, Kennedy told his swimmers the story and promised that if they won, he'd make sure the bus stopped for a steak dinner on the way home; if they lost, they were stopping at a deli for lunch meat. Late in the meet when it was apparent that Hopkins was going to win, Kennedy's swimmers began to chant, "We don't eat baloney, hey! We don't eat baloney, hey!" He says, "At that moment, I made the decision that this has got to be fun. If you're a student at Johns Hopkins, doing what they do, if swimming's not fun a lot of them won't want to do it."

During one of their last workouts before the holiday break, he gathers all the women together near the end of practice. He wants them to divide into teams and race each other in a set of medley relays. The winners will get to eat dinner first when the team trains in Florida. Kennedy blows his whistle and the lead swimmers dive into the water. The others shout and cheer. One by one, they swim their legs of the relay, and at the end the four members of the winning team thrust their arms in the air and dance. No medals, no trophies, no pool records, but they've got bragging rights and in a few weeks they will be first in the food line. They are young, smart, strong, and exuberant, and they believe in their coach. Life is good.