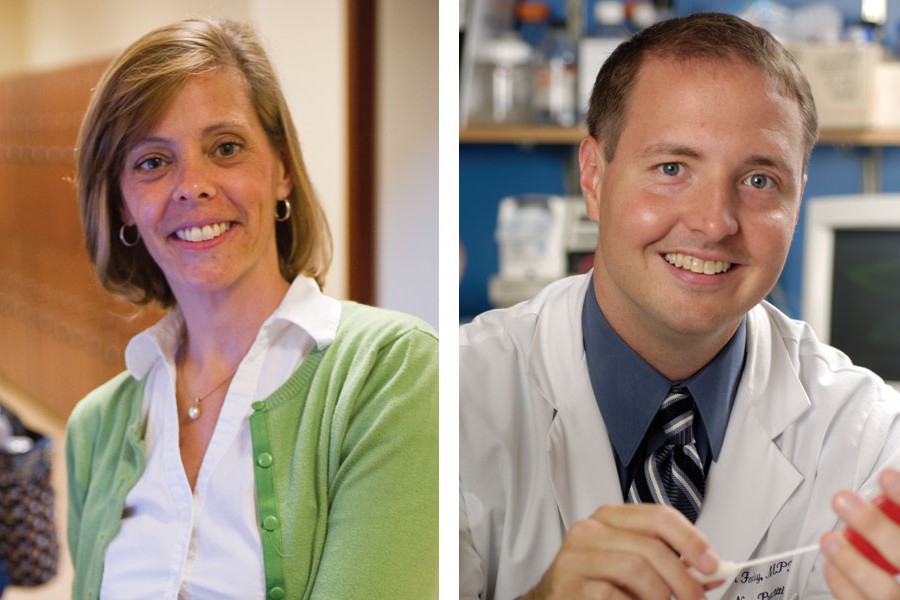

Carrie Tudor, Nurs '08, '12 (PhD), and Jason Farley, Nurs '03 (MS), '08 (PhD), came together over drug-resistant tuberculosis. Tudor, who had 10 years of experience in global health, had come to the School of Nursing to receive a clinical background to augment her master's degree in public health. In the doctoral program, she studied with Farley, an assistant professor in the Department of Community-Public Health. He invited her to work on a study examining nurses' attitudes and practices regarding infection control in 24 South African hospitals that were treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. TB is an enormous health problem in South Africa, where it is the leading cause of death in patients also infected with HIV, and for patients in the developing world, treatment can be prohibitively expensive and lengthy.

Tudor recently began a National Institutes of Health Fogarty Global Health Fellowship, which has taken her back to South Africa, where she'll work on preventing TB and its transmission among health care workers infected with HIV. She will also continue to collaborate with Farley, whose research focuses on the intersection of drug-resistant infections and patients with HIV.

In early September, Farley and Tudor reunited via Skype to discuss their shared dedication to eliminating this curable disease and improving the lot of health care workers. Farley spoke from his office at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, while Tudor called from China, where she was consulting for the International Council of Nurses before heading to South Africa.

Carrie Tuberculosis is everywhere. It's preventable, it's treatable for the most part, and so for me, that's the compelling thing: How do we play a part in preventing the spread of TB, advancing the treatment and cure of TB, and bringing TB down in South Africa? There is such a shortage of health care workers globally, and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. My emphasis is: How do we protect the health care workers that we do have, knowing they can get sick from going to work?In China, I consult for the International Council of Nurses, training nurses on TB. Last year I met a nurse who had been working since 1979 when she graduated from nursing school—30 years working in a TB hospital—and had never received any TB-specific training besides on the job. Doctors get trained; nurses don't.

Jason The work Carrie's doing globally in educating nurses will light a fire that may start as a small flame but pretty soon it's a bonfire. Training nurses in TB is exceptionally important work and she is well-trained to do this. In my own work in infection control during the early 2000s SARS epidemic, I saw how much there is a thirst for education and training from the nursing profession in China. And we see this around the world. It speaks to a lack of recognition of the role that nursing—as a profession primarily of women—plays in many cultures.

C In many countries, especially in China, nurses have a low standing. Everything is very physician-focused, and the nurse is just there to carry out the doctor's orders.

J But I think that we are finally beginning to see countries and organizations understand and recognize the importance of the role that nurses play in a variety of settings—as direct care providers at the bedside as well as direct care prescribers and treatment initiators in primary health care settings.

C Exactly. For example, the training with the International Council of Nurses is called Training for Transformation. It's going on in 16 different countries throughout the world—China, India, Russia, South Africa, Malawi, the Philippines, a few places in West Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda, Swaziland, Lesotho. Our training provides an overview of TB: how it's spread, treatments, multidrug-resistant TB, pediatric TB, infection control, the whole picture. And then the rest of it focuses on best practices and standards for patient care. A lot of it gets nurses to think about the gaps that exist between what they should ideally be doing and their situation. We ask them to think about what they could do in their everyday role as nurses to help close that gap. At the beginning of the training, they think, "I'm just a nurse. What can I do?" But by the end of the week they say, "I am a nurse, and this is what I have to do. If we don't do it, no one else is going to do it." They come in like little lambs and they go out at the end of the week like roaring lions.

J When we go out and do something that might seem like a small training, people, particularly nurses, take that information and run with it. It will trickle down in ways that you could never imagine.

C Yes, they do amazing things. Nurses in China who were trained a few years ago went back and created brochures to share with medical staff in the prisons, educating them on the signs and symptoms of TB, helping them screen for TB and better treat patients with TB. These nurses have gone around to different parts of the province to educate other hospital nurses and include doctors in their training. Several nurses last year did their own research studies; one study has been accepted at a high-level Chinese nursing journal. Another nurse has created a nurse management model that she's testing out for improving patient outcomes with multidrug-resistant TB treatment. We play a very small part—just getting the information in the hands of these nurses so they can go back and institute positive change in their everyday practice, so they can improve best practices for patients with TB, and so they can push their hospital directors and managers to make changes in terms of infection control and other things that will benefit everyone. But there's real potential there to make changes on the ground.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged global health, jason farley, carrie tudor, tuberculosis