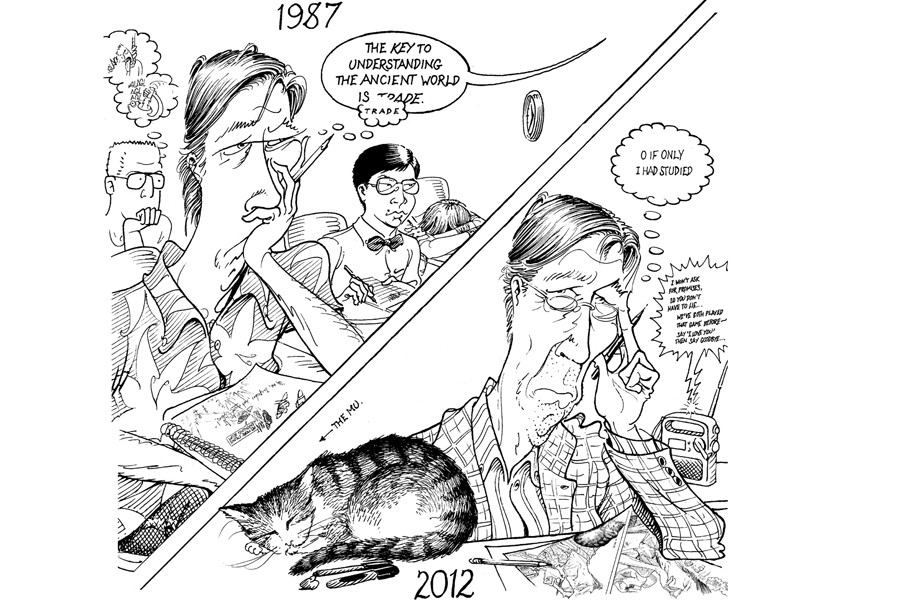

It is simplistic but not entirely inaccurate to say that essayist Tim Kreider drank his way through his 20s, drew his way through his 30s, and has been writing his way through his 40s. As a drinker in his 20s he was, by his own testimony, depressed, though by his friends' testimony still fun to be around. As a misanthropic cartoonist in his 30s he was an adept caricaturist whose drawings were frequently obscene and savagely funny, unless you count yourself among the right wing of the Republican Party, in which case you probably regard them as filthy, blasphemous, treasonous, and worth collecting just in case the day comes when he can be prosecuted.

As a writer, however, Kreider, A&S '88, reveals himself to be well-read, smart, and a fundamentally decent and kind man possessed of rare candor, a pitiless sense of his own shortcomings, and a gift for friendship that makes you wish your number were stored in his cellphone. This summer, Kreider published We Learn Nothing, a collection of 14 essays the author describes as mostly thoughts about friendship and loss. There is indeed much about friends he still sees and friends who have drifted out of touch or cut him off, eccentric friends, and friends who were flat-out nuts. There is also an account of the author trying to feel some empathy for people he despises at a Tea Party rally, his discovery in his 40s of two half-sisters he did not know he had, and a lovely, fond remembrance of a deceased friend who was beloved for the elaborate lies he told. There are rueful tales of Kreider's hopeless love life; a tough and unsparing account of an uncle who died in prison; and yet another version of what he describes as the story he cannot escape telling and retelling, about the time he was nearly murdered in Crete. The book provides substantial evidence that while Kreider is a fine cartoonist, he is a superb essayist, a funny and fluent storyteller who wears his cultural literacy lightly, capable of references, in the same paragraph, to Friedrich Nietzsche, The Dude from The Big Lebowski, and writer Rebecca Solnit, all without affectation. To read "The Creature Walks Among Us," "The Czar's Daughter," "Escape from Pony Island," or "An Insult to the Brain" is to appreciate a mordant but affectionate observer of life's rich pageant, and a craftsman who almost never puts a word wrong.

For example, here he is on the sudden recognition of falling in love: "Someone shows you the rabbit's foot she just bought, explaining, 'It was the last green one,' or simply reaches out and takes your lapel to steady herself as the subway decelerates into the station, and you realize: Uh-oh." On political intolerance: "One reason we rush so quickly to the vulgar satisfactions of judgment, and love to revel in our righteous outrage, is that it spares us from the impotent pain of empathy, and the harder, messier work of understanding." On embarrassment, derived from observing a man with a very bad toupee: "Each of us has a Soul Toupee. The Soul Toupee is that thing about ourselves we are most deeply embarrassed by and like to think we have cunningly concealed from the world but which is, in fact, pitifully obvious to everybody who knows us. Contemplating one's own Soul Toupee is not an exercise for the fainthearted." On friendship: "This is one of the things we rely on our friends for: to think better of us than we think of ourselves. It makes us feel better, but it also makes us be better; we try to be the person they believe we are."

Kreider splits time between an apartment in New York and a cabin in Maryland that he often calls the Undisclosed Location. Off a back path off a back road, the cabin is hard to find even after he has disclosed its location. Formerly used by his family as a vacation house, it is a ramshackle A-frame that as a habitable structure may be approaching its expiration date. Kreider shares it with stacks of books, an increasingly fitful well pump, and his 18-year-old feline companion, who is formally known as The Quetzal but is more often called simply "the cat" or, in deference to her age, "Mrs. Cat." He has been known to rent goats to keep the weeds surrounding the cabin in check. Much of We Learn Nothing was written here.

He says he's never done an honest day's work in his life. That's not true, but it is true that rather than pursue a writing career, he pretty much sat back and let a writing career come to him. For more than a decade, he earned a few thousand dollars a year as a cartoonist—emphasis on few—and was going nowhere professionally, supported year after year by money from his parents, living in friends' apartments when the weather turned too cold for comfort in the drafty Undisclosed Location. He wrote brief essays to accompany the drawings in his three cartoon collections published by Fantagraphics Books (The Pain: When Will It End?, Why Do They Kill Me?, and Twilight of the Assholes), plus the occasional piece of detailed film criticism (Kreider is a film buff), but he did not think of himself as a writer. Then, in 2009, the New York Times started a blog called Proof, devoted to writers musing on the consumption of alcohol, something Kreider knew. He sent an unsolicited piece that the Times titled "Time and the Bottle," about his extended youthful dissipation and the temperance he had eased into as he grew older: "I don't drink like that anymore. My old drinking buddies fell victim to the usual tragedies: careers, marriage, mortgages, children. As my metabolism started to slow down the fun-to-hangover ratio became increasingly unfavorable. I was scandalized to learn that alcohol is a depressant. And I don't miss passing out sitting up with a drink in my hand, or having to be told how much fun I had, or feeling enervated and wretched for days. Being clearheaded is such a peculiar novelty that it's almost like being on some subtle, intriguing new drug."

A literary agent named Meg Thompson read the piece. "I too was getting a little bit older and drinking was becoming not as fun, or rather a little more painful the next day," she recalls. "The way he articulated that, and that sort of state of arrested development, I thought it was beautifully put. I just sort of knew he was a star the minute I read that piece." She got in touch with him—"We met for drinks, of course"—and suggested he put together a proposal for a book of essays. He did, Simon & Schuster liked it for its Free Press imprint, and one day he found himself in New York signing an author's contract, which he describes as one of his life's better moments.

The adult portion of that life, in Kreider's telling, has included a lot of fun but not as much happiness. His childhood sounds sunnier. He grew up in Maryland, first in Baltimore County and then on a 70-acre farm near Churchville in Harford County, as the adopted son of Sidney and Mildred Kreider. Sidney was a physician who for a time was chief of staff health at Johns Hopkins Hospital; Mildred taught nursing at the University of Maryland. "He was an interesting kid," says his younger sister, Mary, who was also adopted and now is a physician in Philadelphia. "He always had a fantastic imagination. He and I would play these elaborate make-believe games together which were his creation—I was always along for the ride." One of those creations was Rabbit Country, an imaginary world populated by superheroes and villains and the evil Skeleton Brothers. When the family moved to the farm, Rabbit Country moved to the barn, where Kreider and his sister played out elaborate adventures that tended to involve saving an imperiled universe. "He always had these fantastic Halloween costumes that involved fake blood," she remembers. She also recalls the time he took a pen and secretly put two red dots on the neck of her Raggedy Ann doll—mark of the vampire.

Kreider recalls that he liked to sketch comic book figures, sometimes inventing his own with the combined features of various characters—for example, Captain America, Pruneface, and Satan in one sketchbook mashup. In middle school, he and a friend would amuse each other by competing to draw the most hideous faces they could imagine. After Star Wars appeared in 1976, he devoted himself to elaborate, detailed renderings of space battles. His dad nudged him into summer art classes at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and after watching him use the family movie camera to make little animated films, his parents bought a more sophisticated Bell & Howell Super 8 with single-frame capability that was better suited to animation. In high school, he used the camera to make short films with his buddies. "These were not good movies," he recalls. "They were much influenced by the humor of Pink Panther films—detective films about bumbling detectives—and I remember we did a slapstick parody of the duel between Hector and Achilles. That was for English class credit, and it got us out of a lot of classes. My dorky friends and I drove around filming ourselves in dorky costumes. That's what I did instead of dating girls. My parents were really good about not expecting me to turn out to be anybody in particular but recognizing my aptitudes and encouraging those. They could tell this was the stuff I was interested in and were very open-minded and kind about it. Most artists are not so lucky. They get the stern patriarchal talking to about how you need a real job."

When he was 14, young Tim drew up a list, a projected time line of his future life. Age 15 through 18, he planned to publish his first book and start selling paintings. Age 19, enroll at Johns Hopkins. Six years later, launch a science fiction saga by writing and illustrating a book he called The Fields of Truniei. Age 29: "Get thrown into a sanatarium." Of that one, Kreider says, "I think that was a ploy. I was going to get thrown into an asylum and then write about it. That was the plan. Not yet accomplished, though there's always time." The life list includes purchase of a home in Montana, the writing of numerous books, a run for the U.S. presidency, and finally, at 94, "Die of natural causes in sleep."

By the time he finished high school, Kreider had that plan on paper but not much else in the way of direction. What he most wanted was to be left alone to draw, write stories, and listen to music. Until the last minute, the only decision about college he could make was that he wanted to study writing. "I just did not want to deal with the hassle and decision of choosing a college," he says. "I still remember that awful period of my life when my parents would say, 'Did you get a chance to look at those college brochures yet?'" He'd already taken writing classes at Johns Hopkins as part of the Center for Talented Youth, so he applied there and was admitted. "I don't know what it's like now, but Hopkins in the '80s seemed like a very tense and joyless place. There were a lot of people there who were premed or prelaw because their parents had decided that's what they were going to do and they weren't the kind of people to whom it had ever occurred to second-guess their parents' ambitions for them. There were people who I would genuinely want to be my primary care physician when they finally got through med school, they were good people, but Hopkins was very much a sink-or-swim kind of place. Nobody was taking you under their wing." He studied in the Writing Seminars with John Barth, Mark Crispin Miller, and Jim Boylan, who is now Jennifer Boylan (Kreider wrote a searching and very funny essay for We Learn Nothing about accompanying Boylan to Wisconsin for her gender reassignment surgery). "For decorum's sake we had to pretend that we worked as hard as everyone else, and we certainly did not," Kreider says. "I was not a good student. I was a goof-off. They weren't optimal learning years for me, or at least not optimal scholarship years, let's say. But I did make friends there, and some of them are still my best friends."

After he graduated in 1988—thanks to an assortment of college credits he'd accumulated in high school, the goof-off graduated from Johns Hopkins in three years—Kreider worked a few years for Maryland Clean Water Action and the Center for Talented Youth and tried to write fiction. He also drew comics. He was getting nowhere with his writing—"I was basically never any good at fiction"—when the Baltimore alternative newspaper City Paper began buying his comics and eventually signed him up as a political cartoonist at wages of $15 per week. "I thought, OK, I guess I'm a cartoonist, because like most people, I keep doing the thing I get positive reinforcement for, no matter how meager that reinforcement might be. My earnings plateaued at $20 a week. But when you're young, just getting published and having an audience means so much to you, you'll work for $15, happily."

When he talks about the decade after Johns Hopkins, "happily" doesn't appear much in his stories. "The 20s aren't a great decade for most people. They were pretty unhappy years for me." He wrote short stories that no one wanted. He flirted with graduate school but can't remember now if he ever applied. He read a lot of Nietzsche, "which is a very 20s-guy thing to read." He went to Europe and nearly got himself killed in Crete, creating that story he'll be telling the rest of his life. During this time his parents subsidized him—he would not approach financial self-sufficiency until a few years ago when he signed his book contract—and let him live for free in the A-frame. He loved a series of women without finding a partner; some of these affairs were not exactly healthy. (He wrote in We Learn Nothing, "There's a fine line between the bold romantic gesture and stalking. . . . Often you don't know whether you're the hero of a romantic comedy or the villain on a Lifetime special until the restraining order arrives.") In 1991, his father died at age 56 from colon cancer, depressing Kreider more than he realized at the time. And he was drinking, apparently quite a lot. He figures he came through the inebrious years unscathed but for the squandered time, and despite the day he and a friend were drinking on the roof of a four-story Baltimore row house and impulsively chased a bottle that was rolling down the pitch: "We were like, 'Whew! Almost lost the Jägermeister!' It didn't occur to me until years later to be relieved that I hadn't fallen to my stupid death."

Though he made no money at it, cartooning for him was important. "Having a thing I could tell people I was—being able to say, 'I'm a cartoonist'—meant a lot to me." For a while, the target of his drawings was mostly the absurdity of men's lives, including his own. Then George W. Bush became president and, appalled by the administration, Kreider had his subject for the next eight years. Looking back at that time in one of his essays, Kreider writes, "I was professionally furious every week for eight years." Boyd White, a senior program manager at the Center for Talented Youth and a longtime friend, says, "Tim would acknowledge that while he was drawing cartoons he spent a lot of that time drinking and being depressed, and a lot of time being very angry, and you can't spend your entire life that way. I think he reached that point where you realize staying that angry is counterproductive and you can't spend all your time drinking and not feel the cost of that."

In 2009, the primary subject of Kreider's political cartooning left office. Fortunately for the cartoonist, later that year he began to find a market for his writing through the New York Times, not necessarily the place you'd expect to embrace someone whose last book was titled Twilight of the Assholes. The 45-year-old essayist can sound wistful about the dirty-minded cartoonist he used to be. He told the writer Noah Brand, "The guy who drew all those cartoons often seems to me now like my younger, drunker, unhappier, more hilarious brother." But his present sober, more responsible life has its merits. Comparing his current state of affairs to that list he made as a teenager, he says, "My 14-year-old self would be ecstatic. My 45-year-old self is pretty happy, too."

Though he does find himself unexpectedly and alarmingly busy these days, what with having one book to promote and another book to write and editors calling to request magazine pieces. Kreider lives within the tension that comes from being a loner who loves and values friendship, and an ambitious artist who often begrudges ambition's demands. He wants readers and book contracts and the opportunity to finally make some money, but prefers an empty day planner. Actually, no day planner. He attracted a good bit of attention last June with an essay in the Times titled "The 'Busy' Trap," in which he wrote: "My own resolute idleness has mostly been a luxury rather than a virtue, but I did make a conscious decision, a long time ago, to choose time over money, since I've always understood that the best investment of my limited time on earth was to spend it with people I love. I suppose it's possible I'll lie on my deathbed regretting that I didn't work harder and say everything I had to say, but I think what I'll really wish is that I could have one more beer with Chris, another long talk with Megan, one last good hard laugh with Boyd. Life is too short to be busy."

Kreider is not sure yet what the next book will be about. "I had 40 years of material to put in book one, and I fear I've used the best stuff and now I got nothing," he says. "But maybe I'm mistaken in imagining that the way I came up with the first book has to be the way that I come up with the second. You don't necessarily have to get stabbed in the throat every time." He's thinking the second book may have more to do with women and the "difficulty of finding something worth loving and committing yourself to." A friend came up with a title that he likes: I Wrote This Book Because I Love You. He's working on a book proposal first because a proposal will generate an advance, a framework, and a deadline. "When I was on my book tour, I went out for a drink with a girl who I guess is in her 20s," he says. "She is mostly a photographer but not quite sure what kind of artist she wants to be, and she confessed to me, after a pitcher or two, that she really wasn't sure she wanted to be an artist. She just didn't want to get a job. And I said, 'That's what an artist is!' We pinky-swore not to reveal that to the public. It's a trade secret."

Friends of his talk about reading early drafts of the essays in We Learn Nothing and finding stories that, in some respects, Kreider has been sorting out for years in letters and conversation. The cartoonist Megan Kelso, who met him in 1998, says, "We started corresponding soon after we met, and I quickly realized that for him letter writing was the sort of early stages of ideas and thoughts for future pieces of writing. He wasn't just dashing off a note. The letter writing was part of his working process." In a four-page cartoon in his book, Kreider lampoons the development, through many retellings over many years, of the tale of his near-fatal stabbing in Crete. Part of the cartoon's text says, "There's a crucial phase early in the telling of a story when it's still fluid; it hasn't yet coalesced into its canonical form. You're still fixing the best details, eliding certain boring or inconvenient facts, learning how to structure and time it for effect." In one panel of that cartoon, Kreider notes, "After a few years, I realized that I was never going to be done telling this story. As long as I kept meeting people, I would always have to tell it again."

He is probably right. So here, as a coda, is the story—honed, polished, and recited by request on a late fall afternoon at the Undisclosed Location: "I had just turned 28 and I was on the island of Crete. I was walking a belligerent drunk girl back from a bar to a youth hostel. She was a belligerent but attractive drunk. On our walk back to the youth hostel we were accosted by someone else who was belligerently drunk. He was from Macedonia and he started yelling at us in Greek, which I don't really speak, but I'd spent enough time in the bars of Baltimore to know the universal language of belligerent drunks—he was trying to pick a fight with us.

"I don't know, maybe he misapprehended the situation and thought that I was forcing her somewhere against her will, which indeed I was but without depraved intentions. I wanted quite honorably to take her home and put her to bed and then resume peaceably drinking myself. So she got into it with him and was flailing out of my grasp, sitting down in the middle of the road and refusing to get up. I finally convinced her that the situation was authentically dangerous and hustled her out of there. I got us to an old mosque from the days of Moorish occupation of Crete, where there was a concert letting out. I figured we were safe. But I guess that guy got away from his friend and ran up behind me and stabbed me in the throat with a stiletto and then ran off. I never even saw him. It felt like getting hit by lightning. There was a very scary 10 or 15 minutes where it certainly looked like I was going to bleed to death. Then an ambulance showed up and I felt a lot better once professionals turned up at the scene and I thought, 'OK, I kept myself alive up to now, now it's in their hands and it's not my fault if I die.' They did surgery on me and I was out for a day or two and then I woke up and was fine. I was pleased to discover that I was still alive. It was a pretty quick existential scare and I was significantly cheered up for a time after that."

That stiletto-induced euphoria lasted only about a year, but Kreider cannot find much to complain about with his present existence. "Life happens the way it does," he says. "I don't think life happens for a reason. It's all a big mess and you just try to make sense of it later. But I think things have worked out about as well as could be hoped. Much of my life has been contingent. You know, I was adopted, and it was a crapshoot who I went home with from the adoption agency, and that worked out awfully well. I think of all the alternative-universe me's, I'm probably near the top. I may not be the winner, but I'm one of the runners-up. Things are going OK in this universe."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged writing seminars, tim kreider