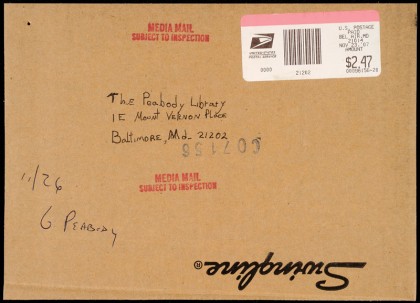

When a slip in Paul Espinosa's mailbox informed him that he had a package, the George Peabody Library rare books assistant had no idea what the small box contained. It had been addressed simply to the Peabody Library and bore no return address. The cancellation read "Bel Air, Md."

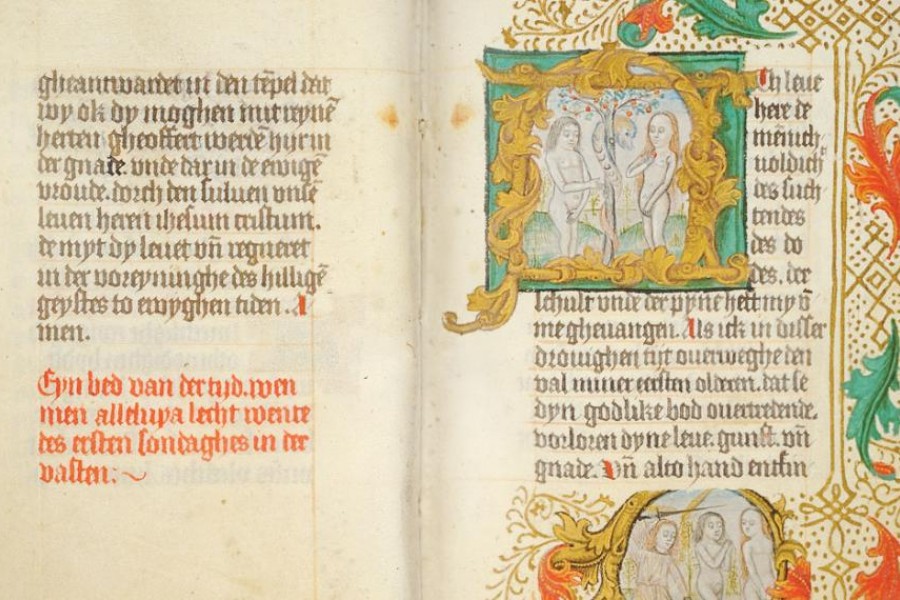

"I opened it up and said, 'Well, this is strange,'" Espinosa recalls. Inside the box was a gorgeous illuminated manuscript, dated 1492. There was no indication that it belonged to the library, but when the library's rare books curator looked at it and recalled something about a manuscript that had gone missing, Espinosa wondered: Is somebody returning this? Just happy to have the book in their possession, they photographed it and assigned it to a shelf. And thus, five years ago, began the convoluted saga of what has come to be known as the Prayer Book of Hans Luneborch, in Low German.

It would eventually take a pair of American and German experts to finally piece together its story, but the process was started by a curious student. In summer 2009, Stacey Lambrow, a graduate student in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences' Master of Liberal Arts program, contacted Espinosa about an internship. She was already interning at the Walters Art Museum across the street and mentioned her interest in its illuminated manuscript collection. Espinosa thought of the returned book. Would she like to work on it as a project?

She would. And the first thing she did was contact James Marrow, a Princeton University professor emeritus of art history and one of the leading experts on Dutch illuminated manuscripts. (The Peabody rare books staff had speculated that the book was of Dutch origin.) Lambrow emailed Marrow with a brief description of the book and a few scans of its pages. The scholar responded almost immediately. As it turned out, Marrow had first inquired about the manuscript more than 40 years prior, when he was a Columbia University graduate student studying the Walters' illuminated manuscripts, then maintained by Dorothy Miner. The 1935 Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada contained a lone entry for the Peabody Library, but that entry was noteworthy because it said the manuscript contained 41 miniatures — a large number for this era. "So I said, 'Dorothy, this manuscript in the Peabody Institute, all those miniatures, is it important?'" recalls Marrow. "And she said, 'Oh dear, don't bother — that manuscript's gone missing.'"

Over ensuing decades, Marrow and other European colleagues contacted or visited the Peabody Library, inquiring about the manuscript, only to be told that it was "not located" and finally just "lost." The academic community gave up on ever seeing it. "It was just a missing manuscript, probably stolen, and it wasn't going to be found," Marrow says. "So I was absolutely floored when I got an email from Stacey Lambrow with a couple of scans of this manuscript. Lo and behold, it was that manuscript."

Soon after, Marrow came down to inspect the book himself and started researching its provenance. Working with Rolf Hammel-Kiesow, deputy head of the Department of History of the Hanseatic League and the Balticregion for the city of Lübeck, Germany, they pieced together a remarkably detailed portrait of the book and the man for whom it was created.

In 1492, Hans Luneborch, a patrician in Lübeck, a northern port city, had commissioned a Dutch artist to illuminate his prayer book for private devotion. Lübeck at this time was a major hub in the Hanseatic League trade alliance that stretched from the southern coasts of the Baltic Sea all the way west to Bruges and London on the North Sea. Luneborch was one of seven sons in a prominent family, and their coat of arms adorns the lower left margin of the first page. More than likely, the book had stayed in the family after his death.

It next turned up in an 1899 collection of manuscripts put up for sale at Sotheby's in London by the Royal Museum of Berlin. Along with 90 others, the book was purchased by a bookseller for £22. The manuscript eventually arrived in the possession of Michael Jenkins, a Baltimore railroad and banking magnate and philanthropist. He was also treasurer of the trustees of the Peabody Institute, and in 1909 donated the manuscript to the Peabody Library.

What makes the manuscript such a find is that it is a vernacular prayer book from Lübeck that dates from the Middle Ages, and few from this era survive. (Lübeck was all but leveled by British bombs in 1942.) The illuminations in the manuscript are attributed to Dutch artists known as the Masters of the Dark Eyes, so called for the shadows that adorn their figures' faces. A substantial 2010 monograph about the Masters of the Dark Eyes doesn't include this manuscript.

"We know very little about private piety and vernacular spirituality in Lübeck, and this manuscript came outof nowhere," Marrow says. "It's a major work of art and object from that time and place. It's an extraordinary example of German-Netherlandish trade and artistic movement. For all of those reasons it's of extraordinary interest to students of manuscript illumination, [and] it's an extraordinary document of cultural and spiritual life at the highest echelons of Lübeck in the late Middle Ages. And I would say in that case, almost unique."

Quite a surprise for something that just turned up in the mail. "This is really our one beautiful, unique work of art," Espinosa says. "It was created for one person for private devotion and that's the way I like to think of it. It sort of came full circle. It was created for private devotion. It ended up in a public library where people could see it and appreciate it and use it. But it went missing, so some- body sort of reclaimed its privacy—and fortuitously it came back."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged libraries, literature, history, peabody library, rare books