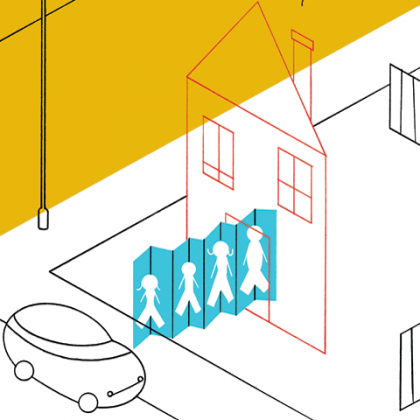

Young adults are living in their parents' homes for much longer or are moving back in with them at alarming rates, the result of economic globalization that has squelched opportunities and wages for young people in the West, says Katherine Newman, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and author of The Accordion Family: Boomerang Kids, Anxious Parents, and the Private Toll of Global Competition (Beacon Press), published in January. Newman, a sociologist, traveled widely to witness how this new living arrangement affects both younger and older generations

Image credit: Laurent Cilluffo

Context

Newman and a cadre of European researchers studied accordion families in Denmark, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, and the United States. Reactions to the accordion-family phenomenon differ from country to country and are highly dependent on each nation's culture. Generally speaking, the Japanese are mortified by the specter of young adults who have not found a meaningful career path in the years following that country's economic "lost decade." Italians are much less concerned and see the new cohabitation arrangements as something that brings families closer together. Spaniards vent their anger at the government and elites for not doing more to help young adults gain a foothold in society. People in Denmark and Sweden, meanwhile, rely on their strong safety-net systems to encourage young adults to live indepen- dently. Middle-class Americans, who in the past may have seen their kids start their own lives after college, seem willing to allow them to stay home longer and gain credentials and exper- ience—advanced degrees, intern- ships—that can help them maintain their middle-class status in the longer term. Newman lives that example: "My son David is 22 and is still living at home. He'll be traveling to Paris to study for his master's degree in international relations. He just finished working 80 hours a week for four months for no money as an intern. He can afford to take an internship because his father and I can support him."

Data

Unemployment figures for young adults have exploded around the world since the 1980s. Nearly 60 percent of Americans 18 to 24 live with their parents — a higher proportion of adult children are living with their parents now than at any time since the 1930s. More than 3 million American parents shared a home with their adult children in 2009, up from 2.1 million in 2000. In Italy, 4 in 10 young men 18 to 35 are living with their parents.

Upshot

"These people aren't slackers, as they were called in the '90s," Newman says. "Young people today are ambitious in general. They're frustrated and disappointed—and they could become embittered. The pathway to adulthood that baby boomers had—a job, independence, living outside their parents' homes, getting married—has been blocked. The whole panoply of the life course has changed. Instead of labor regulations designed to protect workers, we've seen a proliferation of temp and contract work, as well as unpaid internships." And the older generation will long feel the pinch that comes with caring for children well into adult- hood: "We're all involved in this mobility project for the children. For some parents, it will mean they have to work longer because they haven't been able to save for retirement."

Conclusion

"In most of my books, I offer some kind of prescription," Newman says. "But not in this one. I don't know if there's anything we can do. I included Nordic countries because I thought they had the answers to all this. Those countries have high youth unemployment, but they also have free tuition and help young people afford housing outside of their parents' homes. But people worry that they aren't having Sunday dinners together. The question for them has become: If we don't need each other financially, do we really need each other? We like to think that love binds a family together, but economics does, too. There's disconnection between the generations in Denmark and Sweden. They wonder if they love each other enough."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged katherine newman, sociology