Anyone who grew up with the World Book encyclopedia knows what a medical illustration looks like. Open Volume H to "heart" and find an entire page of full-color drawings of the muscular organ, sketches that do not resemble a Valentine's Day card.

Encyclopedias, however, have long been out of sight and fashion in American families, done in by the global search engine. If Wikipedia helped bury Encyclopedia Britannica—which ceased print editions in 2010 after two-and-a-half centuries—has the computer not also sidelined the medical illustrator?

Associate Professor Lydia Gregg, an illustrator specializing in neurovascular anatomy 3D visualization in the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, gets asked about it all the time. She is also an associate professor in the Department of Radiology.

"It's common for those unfamiliar with our field to assume that we're being replaced by the computer," says Gregg, who is a former chair of the board of governors of the Association of Medical Illustrators. "We actually embrace and utilize technological innovations in visualization; we don't fight against them.

"A lot of the fun is keeping up with" technology, adds the Michigan native and Ellicott City resident who likes to sketch when traveling (medieval hospitals, sculptures, specimens in museums of anatomy) and enjoys hiking, graphic novels, and studying the brain and spinal cord.

"Software has not replaced our field's complex creative process, which is backed by medical knowledge. The computer is a tool, much like the pencil. It's still me using the computer."

Hub at Work recently sat down with Gregg to find out how she became a medical illustrator, how her work is used, and why she thinks that drawing the brain and spinal cord is fun.

What led to your life's work?

My mother was a clinical laboratory science lecturer and had been using illustrations in medical textbooks to teach in her own courses. She noticed that I was constantly drawing as a child and loved playing around with science projects as well. My mother suggested medical illustration as a potential career, and I was immediately hooked.

My undergraduate degree is from the University of Michigan [2005]; I studied scientific illustration and figurative sculpture with a minor in biology.

After graduation, I moved to Baltimore for my master's in medical and biological illustration at Johns Hopkins [2007]. I now teach at this graduate degree program, which combines pre-clinical courses from the School of Medicine with illustration, animation, and interactive media courses.

Much of your work involves creating illustrations and 3D models for doctors and researchers. What is the process from getting the assignment to finished product?

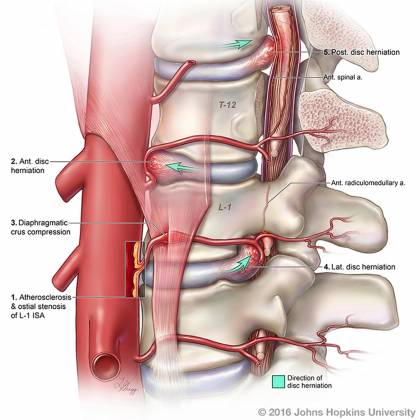

Before I begin to sketch, the first and most important step is to fully understand the subject matter. I typically begin with small pencil drawings and try to integrate information from pathological specimens and 3D radiological scans as I draw.

To make illustrations useful as teaching tools, I design them with scientific learning theories in mind. Before starting the final piece, I communicate with the doctor or scientist I'm working with to make it as accurate as possible.

Image caption: Cord ischemia illustration by Lydia Gregg

I then complete the work in a variety of ways, sometimes coloring the work in Adobe Photoshop, sometimes creating the piece entirely within 3D software like Zbrush or Cinema 4D. If the piece is a 3D print, then I extract 3D models from radiological scans, like MRI data, using Osirix or 3D Slicer.

You also do animation projects.

Yes, I recently completed an animation for the [Johns Hopkins] Lyme Disease Research Center. Prior to this project, there was no comprehensive animation about Lyme disease transmission and treatment online that offered accurate information for patients.

[Editor's note: The Lyme Disease Animation: Infection, Immune System Evasion & Progression won an Award of Excellence in August from the Association of Medical Illustrators.]

You start with a script [which Gregg also helped write], then you add images to create a storyboard, which depicts important moments in the animation and serves as a guide for discussions with clients.

The draft looks like a comic book—it's a narrative with heroes and villains. I'll receive questions like "Can you add more spirochetes near the tick's mouthparts?" Spirochetes are the bacteria, the villains of a Lyme disease narrative.

You are part of a team given a JHU Discovery Award this year for a project intended to help opioid abusers remain drug-free. Can you explain?

Dr. Seun Falade-Nwulia is leading our effort to develop and assess a mobile health app for people with opioid use disorder.

When patients are hospitalized for an overdose and separated from daily social influences, there is a window to start medication-assisted treatment, which uses medications, counseling, and therapy to reduce opioid use and improve quality of life.

I'll be designing and creating the visuals for the app and helping create visual stories to enhance engagement of patients with their recovery plan. We're working directly with counselors, patients, and other health care professionals to develop the app.

This research is truly patient-centered, so I don't know exactly what I'll be creating yet. The patients and their peer counselors will lead in describing what they think will work best, based on their own experiences.

What's so fun about drawing the brain and spinal cord?

It's an area of anatomy where new ideas are constantly being published, whether it's new classifications of neurons, precise pathways for forming memories in the hippocampus, or novel procedures for treating problems with the blood vessels in the brain. I try to offer new ways of understanding these topics through visual communication.

Posted in News+Info

Tagged who does that?