Peter Achinstein recalls that he was "driving 70 mph down the highway" one day in 2014, when his daughter Sharon called from the UK to say she was considering a job at Johns Hopkins.

"I was shocked," Achinstein says. "It was hard to keep the car going."

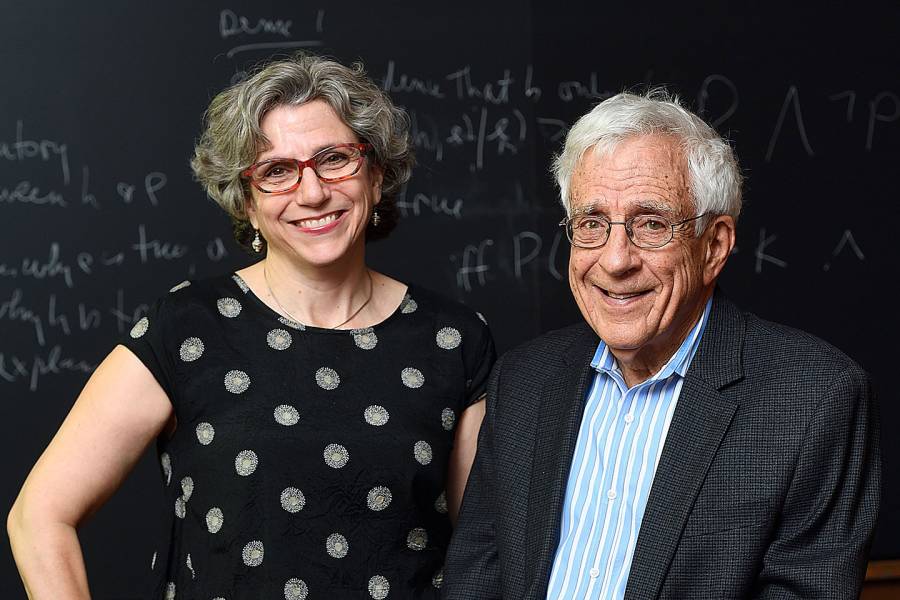

Achinstein, a celebrated analytic philosopher, had been a professor at Hopkins for nearly five decades at that point. Although his daughter Sharon Achinstein had followed him down the path to academia—pursuing her own interests in early modern literature—the two never expected their careers to intersect so directly.

Sharon was teaching at Oxford University when Hopkins offered her the position of Sir William Osler Professor of English. It began to seem like an ideal fit: a return to her hometown of Baltimore, joining a department she respected—"plus my dad was here," she says.

The two Krieger School professors, father and daughter, sat down with Hub at Work recently to talk about their Hopkins history and the past five years of sharing an academic home.

Q: Peter, how did you first arrive at Hopkins?

Peter: In 1962, I got a call from Hopkins for an interview. When I came down, I remember parking on Charles Street—it was much less crowded then—and some guy coming over, asking, "Do you know where I can get a job?" And I told him, "I'm trying to get one myself."

Two months later, I got the offer from Hopkins and accepted it—and I've been here ever since, aside from visiting appointments.

My family first lived in a little rowhouse in Northwood. My son, Jonathan, was an infant then, and Sharon and her sister, Betty, came next—both of them born at Johns Hopkins Hospital. I was very close to my parents, and one advantage to Hopkins was I could visit them almost every weekend, in Bethesda, Maryland. My father, Asher Achinstein, was on President Eisenhower's Council of Economic Advisers.

Sharon: My grandfather was a PhD in economics from Columbia, so our family has three generations of academics. In his will, my grandfather left the endowment for two lecture series at Hopkins, one for the Department of Near Eastern Studies and the other for my father's Center for History and Philosophy of Science, so [to her dad] he was obviously committed to Hopkins and proud of you as a professor.

Q: Sharon, growing up, what do you remember about Hopkins?

Sharon: Sometimes I'd come with my dad on campus Saturday mornings and sit in the secretary's office drawing while he worked. It was a treat. I remember my father's colleague Dr. Kingsley Price, who was blind, would ask, "Is that Sharon or Betty?"—he could tell a little girl was there.

And we'd go to picnics and fairs at Hopkins. I also remember the Vietnam protests on campus.

Peter: That was huge. I was on the Academic Council at the time, which was at one point invaded by angry protesters who took over parts of the campus.

Q: How did you begin to understand your father's work as a philosopher?

Sharon: My father would sometimes bring home philosophical questions to the dinner table. So I remember, for example, "the raven paradox."

Peter: It's a puzzle about the nature of evidence—a paradox because you start with assumptions that seem obvious and end up with a conclusion that is absurd.

Sharon: So I knew philosophy as a temperament and a quizzical habit of argument and interrogation. I honestly didn't know until I was in high school that my father was looking for the truth—and that appealed to me because I was literary and could appreciate a quest for the truth.

Around the time my brother was at Hopkins as an undergrad [Jonathan Achinstein, Class of '83], I remember my father using me as an example in his lectures, teaching something called decision theory.

Peter: Part of my logic courses deal with formal probability, and decision theory gives a way to make decisions based on numerical probabilities and utilities. With Sharon, we used it to explore all the possible consequences of a decision she had to make in high school: "Play lacrosse" or "Don't play lacrosse."

Once we computed everything, our numbers said she should not play. And she said, "Well, I don't like that. It's not to my advantage. Let's change the numbers." So we did it again with new numbers, and she came out the way she wanted. And I used this as an example in my classes to show how decision theory works and how it doesn't always give you the answer you like.

Sharon: Bottom line: I did play lacrosse.

Q: How do you think your father's career affected your own academic path?

Sharon: Well, education and knowledge-seeking were always very valued in our household, and reading books. When I was in high school, my dad somehow got me a library card at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, and that was amazing to me. I wrote my papers there, and I started to appreciate what being in a library could be like. But I didn't know I wanted to be an academic until later, in college.

Q. You two have some other institutions of overlap, beyond Hopkins.

Peter: We both went to Harvard as undergraduates. Sharon was always an outstanding student, Phi Beta Kappa.

Sharon: So were you.

Peter: I also got my PhD at Harvard. During that time I attended Oxford with a traveling fellowship—it was the hottest place to be in philosophy in the early '60s. And Sharon later taught at Oxford.

Sharon: I married a Brit, and my husband and I both got jobs at Oxford. I worked there for 12 years and raised my kids there.

Q. How did it come about that Sharon ended up at Hopkins?

Sharon: I'd left Baltimore at 18 and hadn't really been contemplating moving back to the States. But at some point I saw that the JHU Department of English was looking for a Renaissance scholar, and it seemed like a perfect fit because I knew the city and it was a fantastic department—I didn't even get into graduate school here, so I knew it was good! [Note: She received her PhD from Princeton.] Plus, my dad was here.

Peter: When Sharon was in the review process, I remember getting a call from her saying, "Dad, don't f*** it up." And I thought, that's going to be the title of my new book.

Q: What's it been like working at the same place?

Sharon: When I first started here in 2014, I appreciated the legacy my father had of years of service, and this vision of Hopkins from an earlier time, as the university was starting to expand. I felt reverential about that, and even as Hopkins has changed, I feel continuity with that era. The colleagues of my dad's generation, some of whom are retiring, have had a special bond with me because they feel like it's part of that earlier Hopkins they knew.

Q: Where do your academic interests coincide?

Sharon: We're both in the humanities, and we both enjoy the classroom and love teaching.

Peter: Yes, and that's the main reason I don't want to retire. I enjoy teaching. That and writing keep me questioning and young, or at least feeling young.

Q: How often do you see each other on campus?

Peter: She has her own academic life and she's very busy. But we do make it a point to get together and talk business and family stuff.

Sharon: We'll make a date for lunch. If my kids are on vacation, sometimes I'll bring them to work with me and they'll see grandpa for a surprise visit.

Peter Achinstein, founder and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for History and Philosophy of Science, is the author of eight books including Particles and Waves (winner of the prestigious Lakatos Award in 1993—and dedicated to Sharon) and his latest, 2018's Speculation: Within and About Science. In 2011, Oxford University Press published a festschrift in his honor, with 20 essays on his work by distinguished scholars in his field, and his replies to each.

Sharon Achinstein's scholarship explores the intersection of literature and political communication in the early modern period, focusing on issues of tolerance, religious dissent, and women's participation. She specializes in John Milton and is currently completing an edition of the poet's prose works while teaching a freshman seminar called How Not to Be Afraid of Poetry.

Posted in News+Info

Tagged family snapshots