Johns Hopkins faculty and staff are a notoriously innovative, curious, and extremely busy cohort. Yet in the midst of an unusually hectic year, they made it a priority to set aside some time to read many good books—sometimes at the suggestion of their colleagues and friends (or even with their friends in at least one case). Here are some of their favorite reads of 2025.

Narges Bajoghli

Associate professor | SAIS

I recommend Jesmyn Ward's Let Us Descend. It is a masterpiece of historical reclamation and lyrical force. Ward transforms the harrowing journey of an enslaved young woman into a mythic epic of spiritual survival, weaving African folklore with stark, breathtaking prose. This novel is devastating yet profoundly beautiful, a necessary meditation on memory, love, and the human spirit's endurance in the face of horror. It is the kind of book that reshapes your understanding—not just of history, but of literature's power to witness and transcend. An unforgettable, essential read.

Sarah Szanton

Dean | Johns Hopkins School of Nursing

SNF Agora Institute director and dear friend, Hahrie Han, coaxed me into reading War and Peace. Over drinks at Dutch Courage, she urged me to read it with companion book Tolstoy Together: 85 Days of War and Peace with Yiyun Li. I'm so glad I did! Reading a timeless novel about non-famous individuals shaping history fortifies me for our country's current turbulence. Some favorite characters were minor in page-space but crucial to plot or illuminated main characters' development. Such a magnificent canvas! And reading alongside the companion book felt like joining a glorious ongoing conversation of perceptive readers.

Amy Lynne Shelton

Executive director | The Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth

I was seeking a literary landmark earlier this year when I visited Sweny's Pharmacy in Dublin, one of numerous sites around the city made famous by James Joyce's novel Ulysses. From my visit I also came away with one of my favorite reads of the year: Can I Have Your Charm Bracelet When You Die?: A Dublin Childhood, by Shelia Hamilton. This memoir is such a beautiful tribute to growing up in Dublin—I am transported there every time I open the book. Hamilton, an artist, barrister, and actress, is a child of the '70s and '80s whose working-class childhood resonated with me, so much so that I am looking forward to reading it again and again.

Mathias Unberath

Director of research, interactive, and embodied AI | Data Science and AI Institute

Recognize the deep frustration of last-minuting material for the thing you said "yes" to months ago without reflecting long enough whether you actually want to do it? In academia—like self-employment—the pressure for advancement is never-ending and thanks to our increasing connectedness, neither is the wealth of opportunities. Realizing this source of frustration in my own habits, I found Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown to provide some interesting thoughts. Like most self-help books, the essence can be summarized compactly: Say "no" more to merely OK opportunities so that you have more bandwidth to nail those "hell yes!" opportunities that ultimately really matter. Let's try, shall we?

Kathleen Barry

Associate director | National Fellowships Program

The best book I read this year was the final installment in Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, a blacksmith's son who rose to become top advisor to Henry VIII, only to be executed in 1540. I read the first two books, Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring Up the Bodies (2012), many years ago, and finally turned to 2020's The Mirror and the Light this year after re-reading the first two. Having trained as a historian, I admire top practitioners of historical fiction who can transport readers to the past and flesh out characters imaginatively in ways evidence-bound historians cannot. For me, Mantel is the master, and I find her intellectual and emotional portrait of Cromwell incredibly compelling. His downfall and death in the final book were no surprise, but saddened me more than I anticipated. The superb two-season BBC adaptation of the Wolf Hall trilogy is a bonus to enjoy after reading.

James Glossman

Lecturer | Undergraduate Program in Theatre Arts & Studies

I've had some very good luck this year with lots of very different works, both new and old: fiction, history, memoir, biography—so it's a real challenge to pick just one title. I think Amanda Vaill's breathtaking book Hotel Florida—about the vast range of major writers and artists (Gellhorn, Hemingway, Capa, Taro, Orwell, Dos Passos, Hughes…) who became involved in reporting, and sometimes fighting in, the Spanish Civil War—truly feels like something new, a fresh and powerful angle on a hinge-point of the 20th century, and thus today. Fast-moving, full of surprises, while at the same time both deeply researched and just as deeply humane. A real page-turner.

Ralph Etienne-Cummings

Professor | Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Ted Chiang's Exhalation is a scientifically and philosophically thought-provoking collection, timely and beautifully written. He weaves complex concepts into elegant storytelling, making the book both illuminating and gripping. The work consists of short stories exploring themes such as an alternate world confronting its demise due to the second law of thermodynamics; the tension between what Yann Martel called "yeast-less factuality," the rigid accuracy of written or video records, versus the fluidity and fragility of oral histories and human memory when serving social purposes; and the question of free will in a universe where timelines diverge based on decisions, yet remain interconnected, allowing outcomes to be known, judged, and even envied. These are just three of the nine stories, which also delve into profound ideas about time, artificial intelligence, and the nature of existence. Think Black Mirror in prose, only far more cerebral.

Emily Riehl

Director of graduate studies | Department of Mathematics

By the time I stopped by the going-out-of-business sale at the Barnes and Noble inside the Johns Hopkins Campus Store late last spring, there were very few titles remaining. I bought the only book I'd heard of, which was Kathryn Schulz's memoir Lost & Found. Now that I've read it, this feels like a very lucky discovery indeed. This felt like a more accessible continuation of the autotheory genre, which I first encountered with Maggie Nelson's The Argonauts. Schulz writes beautifully about the experience of losing her father shortly after finding her life partner and the experience of losing and finding more generally. I cried during the first section, swooned during the second, and recommended the book to several old friends immediately after finishing.

Jerry L. Burgess

Director | Environmental Science and Studies

I just adore woodlands and forests of Eastern North America, so the title of North Woods grabbed my attention right away. However, I was in for a real treat from one of the most genre-defying books I've read in that the central character of this historical fiction book is a place and not a person. This is a magical story about transitions, the ephemeral nature of people, and natural succession in New England from precolonial times through the present day and beyond, from the perspective of a single house in Western Massachusetts. There are vivid descriptions of nature, rich language, and the appearance of ghosts. What is not to like!

Nathan Dennies

Associate director of communications | Fund for Johns Hopkins Medicine

How do you raise a genius? It's one of the questions Helen DeWitt explores in her brilliant, funny, and moving novel, The Last Samurai. The novel follows Sibylla, a polyglot and Oxford dropout, as she raises her brilliant son, Ludo, beginning with Ancient Greek lessons at age 3. You'll be learning alongside Ludo, and part of DeWitt's brilliance is making this fun, even inspiring. But what Ludo really wants to know is the identity of his father, and he sets off on a quest across London to find him. DeWitt's novel resonated with me as a parent. How do we raise our children in a society where literacy rates are declining and critical thinking is outsourced to ChatGPT? On the other hand, what do we deny our children when we obsess over their potential?

Melinda Buntin

Bloomberg Distinguished Professor | Health Policy and Economics

Adam Ross's Playworld was my favorite book of the year, and I read a lot of literary fiction in 2025. When it came out last January, The Washington Post titled its review, "Playworld is so good, it will give readers hope for the year ahead." I'm planning to give it to a few readers on my list this holiday season with that in mind. They won't be people who want a "feel-good" book, though; the protagonist is a child actor in 1980s New York City, and the adults around him are oblivious at best. What will draw them in is the gorgeous prose, the evocative scene-setting, the sharp edge on the nostalgia, and the way the novel spurs us to think about the interplay of culture and politics in America.

Angus Burgin

Associate professor | History

Hernan Diaz's Trust begins as a story about financial markets in the 1920s, and brilliantly shows how the people who are best able to anticipate and manipulate them become imbued with mystical powers, however unremarkable their private lives might be. In itself, that story resonates in our own age of speculative manias and arcane financial instruments. But its narrative then devolves into a tangle of conflicting perspectives—a journalistic takedown, a celebratory autobiography, a secretarial memoir, a lost diary—that form both a riveting puzzle and a reminder that all history is perspectival, and that words can hide as much as they reveal.

Anand Pandian

Professor | Anthropology

The new novel by Megha Majumdar, A Guardian and a Thief, is a real page-turner and also a compelling study of human nature. Majumdar is an alum of our department of anthropology at Johns Hopkins, having graduated with a master of arts degree in 2015. There's a deep ethnographic sensibility to the portraits she sketches in the novel, in her keen eye for detail, and her ability to lend the smallest moments a sense of beauty and poignancy, even in the midst of wrenching impasse. The characters and their dilemmas have stayed with me as companions to think with, relatable others wrestling with the challenges of living and caretaking in an often monstrous and indifferent world.

Elisabeth Long

Dean | Sheridan Libraries and University Museums

A group of college friends and I have been reading our way through all of Shakespeare, and I have been both surprised and delighted to discover the number of plays of his that I had never actually read. One that stands out and that I would recommend is Coriolanus. Little performed, perhaps because the main character is not particularly likable, it is actually a wonderful study of a rather complex character who was successful in battle but not in navigating peacetime. His rigid pride and consuming rage lead him down a path of self-destruction that takes him from devout patriot to ultimate betrayer of the city he loves. I pick this one out in particular because of how much it resonates with today's politics. And I recommend that you read it out loud—like all of Shakespeare's plays, they are meant to be heard, and reading them aloud really makes his language sing. Our group has enjoyed doing table reads first, and then holding a seminar to discuss the play—double the fun!

Julie Kay Lundquist

Bloomberg Distinguished Professor | Atmospheric Science and Wind Energy

As a new resident of Baltimore, I enjoy learning more about our fascinating city and how the disparities we see have been shaped historically. I read Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City by Antero Pietila before moving to JHU but reread it again this semester now that I know Charm City's neighborhoods better, and I highly recommend it and his other great Baltimore study The Ghosts of Johns Hopkins: The Life and Legacy that Shaped an American City. On the other hand, some fun escapism is sometimes necessary, in which case I recommend Stephen Graham Jones' superb and chilling horror novel The Only Good Indians. Not only will he have you jumping at shadows around corners, but he also shares a nuanced insight into modern Native American life.

Dora Malech

Professor and department chair | The Writing Seminars; Editor in chief, The Hopkins Review

If you're looking to broaden your literary horizons, the new Best Literary Translations series from Deep Vellum is for you. The series is edited by Noh Anothai, Wendy Call, Öykü Tekten, and Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún, with a different guest editor every year. Best Literary Translations 2025, guest edited by Cristina Rivera Garza, is the second in the series; BLT 2026 will be guest edited by newly appointed U.S. Poet Laureate Arthur Sze, so stay tuned. The series "celebrates world literatures in English translation and honors the translators who create and literary journals that publish this work." I love encountering new-to-me writers, translators, and literary journals in this anthology, and the translators provide brief commentaries on their work to illuminate both cultural context and creative process.

Martha S. Jones

Professor | Department of History and at the SNF Agora Institute

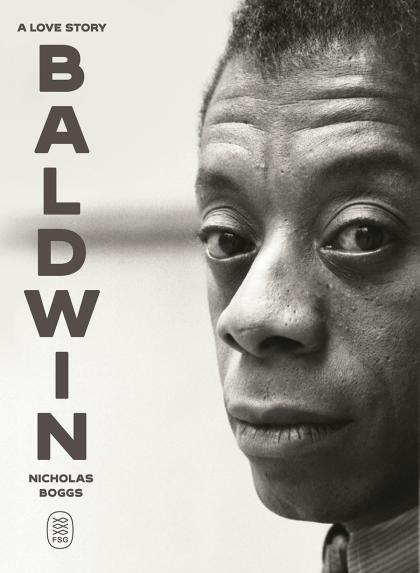

I picked up Nicholas Boggs's superb biography, Baldwin: A Love Story, already on a quest to better know writer and activist James Baldwin. Baldwin had inspired my writing and teaching. Boggs permitted me to discover what moved Baldwin: ideas, and also longing, desire, and a need to love and be loved. Bravely, Baldwin always defied binaries: Black/white, straight/gay, family/stranger, American/European, northerner/southerner. A consummate scholar, Boggs shares his decades-long research journey. The result is a compassionate portrait of one of the 20th century's greatest minds, a book that asks readers to understand Baldwin on his own terms rather than their own.

Posted in Voices+Opinion