The impact of cuts to federal research funding has been the subject of several national news stories featuring Johns Hopkins University scholars in recent weeks, including accounts of how reduced funding might derail lifesaving cancer research and how grant terminations are already affecting some of the nation's most promising young scientists.

Promising cancer research at risk

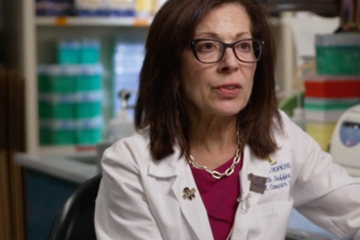

Veteran journalist Ted Koppel explored the human toll of potential cuts to cancer research funding in a report that aired on CBS News Sunday Morning. Among the experts he spoke with was Elizabeth Jaffee, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

"We are in a technological revolution in cancer research," Jaffee told Koppel. "We are rapidly making discoveries that we couldn't even do 10 years ago."

As an example, Jaffee said she and her Hopkins colleague, Neeha Zaidi, are making tremendous strides in developing a vaccine to prevent pancreatic cancer—one of the deadliest types of cancer—from recurring. Their work has shown tremendous promise for a small cohort of patients who participated in a trial and are now doing well despite the odds.

"This is not a cancer where sometimes it looks less aggressive than other times," Jaffee said. "This is a cancer that uniformly—it doesn't matter who you are, it comes back."

But their lifesaving patient trials and similar cancer research endeavors across the country face uncertainty amid the prospect of federal budget cuts, with the National Cancer Institute—part of the National Institutes of Health—potentially having its funding reduced by billions of dollars annually.

"Progress is going to be proportional to investment," said George Weiner, a cancer researcher at the University of Iowa. "So progress is not going to totally stop if funding drops dramatically. … But that's not the case for patients. Our job as researchers is to bring those advances to help those patients as soon as possible. Because those patients can't wait."

Grant terminations for early-career scholars

Some NIH cuts are already having a tangible impact—as a recent New York Times article explained, hundreds of promising young scholars across the country have seen their NIH grants terminated.

The list of scholars highlighted by The Times includes two from Johns Hopkins:

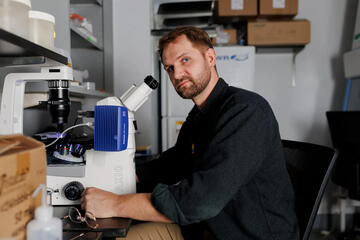

Lucas Dillard, a PhD candidate studying molecular biophysics at JHU, was among the recipients of a prestigious National Institutes of Health grant beginning last year. Dillard, who was raised by a single mother in rural Appalachia, was among a select group of early career scholars to earn a grant through a highly competitive program that provides financial support to the nation's most promising doctoral students so they can continue their scientific research.

Nicole Gross was in line to receive a similar NIH grant beginning this fall. Gross, who grew up on a dairy farm in rural Michigan, started at Hopkins as a technician and progressed to the doctoral program in the immuno-oncology lab of Won Jin Ho, where her research focuses on understanding metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Their grants were eliminated as part of a series of broad and sweeping cuts to programs and projects deemed by the federal government to be using "race- and sex-based preferences under the guise of so-called 'diversity, equity, and inclusion'" and thus not compliant with a January executive order forbidding such practices.

But as The Times reports, in the rush to comply with the order, the NIH has canceled diversity programs "intended to make science less elite, by developing a pipeline from poorer areas of the country that tend to be more conservative."

The "push to end DEI," The Times adds, "has been a blunt instrument, eliminating highly competitive grant programs that defined diversity well beyond race and gender." These programs were intended to bridge America's scientific divide:

Scientists who run university labs, like professors in general, tend to come from families with higher incomes, their paths smoothed by the advantages of high schools with rigorous courses or parents who can help them get early internships. One recent study found that they are 25 times more likely to have a parent with PhD.

The NIH had long recognized this, and its diversity grants cast a wide net to attract people it defines as "underrepresented" in scientific research. The grant Mr. Dillard received was typical: open to students whose parents didn't graduate from college; those who had been in foster care, homeless, or poor enough to receive food assistance or Pell grants; people with disabilities or from rural areas.

As Mr. Dillard said, "I don't know anybody else at Hopkins who looks or sounds like me."

Additional coverage

An article published by The Baltimore Banner explored Johns Hopkins University's wide-ranging efforts to make the case, both publicly and privately, for the critical importance of federal funding for university research and the "therapies and cures that spring from the science performed with taxpayer dollars in Hopkins' labs."

The Washington Post highlighted a year-long seminar class for first-year JHU undergraduates called "Democratic Erosion", in which a small group of students with varied backgrounds and ideological leanings discuss U.S. politics and the state of global democracy.

Posted in Science+Technology, Politics+Society

Tagged nih funding