Johns Hopkins engineers are developing treatments for Type 1 diabetes that don't rely on daily insulin injections or wearing an insulin pump to manage blood sugar levels. Instead, their new cell-based immunotherapies aim to prevent the immune system from attacking the insulin-producing cells in the first place.

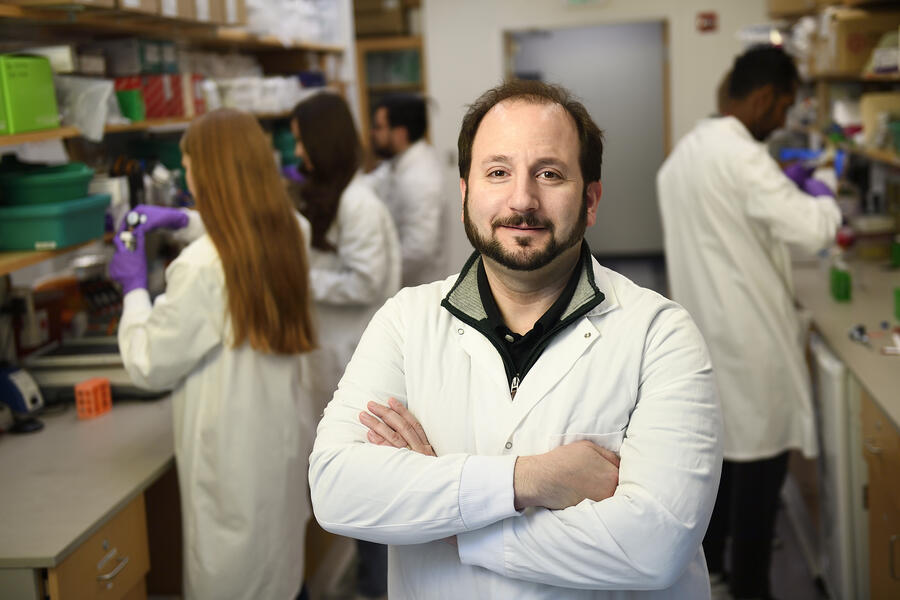

"We want to design a better solution for Type 1 diabetics that provides long-lasting benefits, can improve their overall quality of life, and lessen the risk of complications," said Joshua Doloff, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and co-principal investigator.

Type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes, is an autoimmune condition in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. The Centers for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that there were approximately 1.4 million people with type 1 diabetes in the U.S. in 2020, a number that is projected to grow to 2.1 million by 2040.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health's Division of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Doloff is spearheading the project with Jordan Green, vice chair for research and translation in JHU's Department of Biomedical Engineering, and colleagues in the university's Translational Tissue Engineering Center (TTEC).

The team is exploring a novel approach that involves creating biodegradable nanoparticles designed to deliver genetically engineered cells, called autoantigens, directly to the liver's immune cells. By introducing these specialized autoantigens, they aim to stop the autoimmune response that characterizes Type 1 diabetes and reboot proper insulin production in the pancreas. If successful, this will be an important development toward freeing patients from the ever-present burden of managing diabetes, the researchers said.

"As biomedical engineers, we're thinking about how the discoveries we make in the lab will make life better for the people who have to manage diabetes every day," Doloff said.

The immunoengineering technologies being created in Hopkins labs also promise to improve treatment for other highly challenging conditions. For example, Doloff's lab is working on new drug delivery systems for treating ovarian cancer that could reduce side effects while still maximizing the chances of successfully destroying cancer cells.

"We are hopeful that NIH funding will help us expand upon the current strategies for treating diabetes and other diseases that have long been difficult to treat," Doloff said. "The goal is to be able to continue building on decades of research to deliver the most effective and personalized therapies to more patients."

Image caption: Joshua Doloff, center, with colleagues

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged nih funding, diabetes