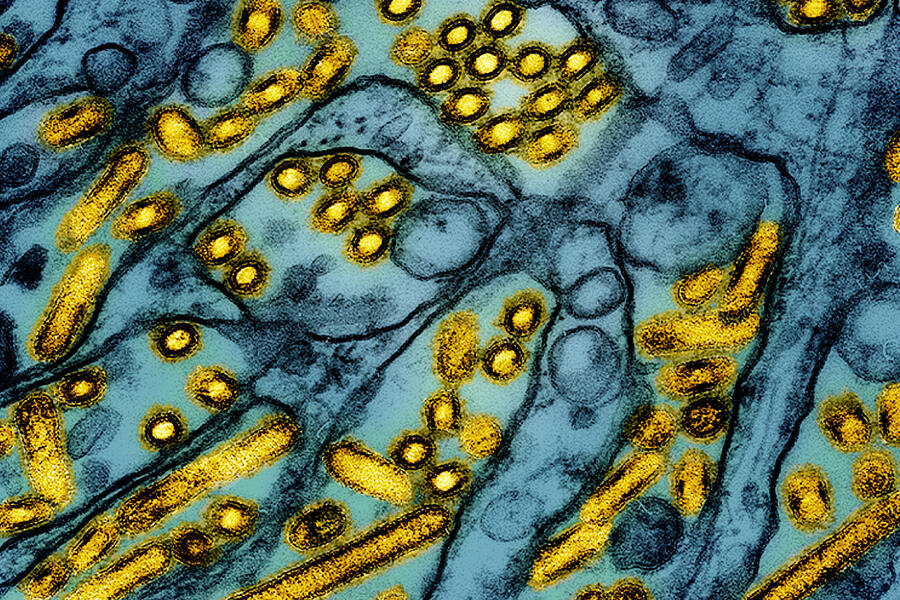

Bird flu continues to spread across the United States and behave in uncanny ways.

Last week, a Louisiana resident became the first human in the country to die from the H5N1 influenza virus, after being hospitalized with severe illness. The patient, who was older than 65 and had underlying health conditions, contracted the infectious disease from exposure to wild birds and a backyard flock of chickens, the Louisiana Department of Health reports.

Experts monitoring and investigating the virus say the news is not a reason to panic, and the risk remains low to the public. But the rapid rate at which H5N1 is infecting not only wild birds and poultry but also cattle and other mammals, including humans, raises concerns for infectious disease experts, who say that additional tracking and preventive measures are necessary: If the virus mutates in a way that allows it to pass from one human to another, experts fear it could become an epidemic or pandemic.

Key Takeaways

To help prevent the spread of avian flu:

- Avoid raw milk products and raw or undercooked meat products, including eggs; consume pasteurized milk and pasteurized milk products only

- Do not touch or handle dead or dying birds, animals, and mammals

- Protect your pets: Keep cats indoors, keep dogs away from areas with migratory birds, and avoid feeding raw milk and raw meat pet food diets

- Contain backyard chickens and change your clothes and wash your hands after visiting the coop

"At this point, we've seen no evidence of human-to-human transmission," says Johns Hopkins molecular epidemiologist and environmental microbiologist Meghan Davis. "Signs indicate that it could happen, but no one knows for certain whether it will or not."

Davis, who spent more than a decade working as a veterinarian, is an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins' Bloomberg School of Public Health, with joint appointments in the School of Medicine. She sat down recently with the Hub to discuss the evolving bird flu situation and share advice for the public on how to stay safe.

H5N1 has been on our radar for a while. What makes the virus newly concerning?

Usually, when we see an outbreak, it flares up and then goes away. The challenge we've had with this strain of H5N1 is that it's had a staying power not seen in prior avian influenzas, [along] with a plot twist earlier this year when the virus got into dairy cows. This isn't typical for avian influenzas.

In cows, H5N1 infects the mammary gland, so milk is something we're really worried about now. Another unusual factor, however, is that the virus isn't just infecting cows but also other mammals, from foxes and bears to field mice, squirrels, and even domestic cats. In South America, the virus caused a high number of marine mammal deaths, which is also unusual.

The adaptability of this virus and its staying power—and now this new way of being exposed through milk from cows—means it's creeping closer and closer to the threshold of concern from a pandemic potential perspective.

What symptoms is the condition causing? Are there differences between infections caused by cows or birds?

H5N1 contracted from wild birds and backyard flocks tends to cause more severe respiratory symptoms and illness. This is more [akin] to older strains of bird flu we've seen, which have a fatality rate in humans of as high as roughly 50%—not a number anyone wants to hear. But it does mean that human exposure to the virus could come with tragic consequences.

People who work with dairy cows and poultry infected with the dairy-associated genotype often present with upper respiratory symptoms, fever, and conjunctivitis, [an infection or inflammation of the eye that causes swelling and redness and can be itchy and painful]. It's a milder form of illness more like the [seasonal] flu, although conjunctivitis can be the most bothersome symptom, and it can be severe. The [working] hypothesis is that dairy farmers get splashes of milk in their eyes, or they touch their eyes, while working with cows in the milking parlor. Because they're milking cows at face height, [dairy farmworkers are susceptible] to aerosolization or splash droplets in the face area.

Why the difference in severity and symptoms?

Backyard poultry and wild birds appear to expose people to an H5N1 genotype that differs from the genotype associated with dairy farms, with the strain of the virus spread by poultry and birds leading to more severe illness. This happened, for instance, in the sad news out of Louisiana, with someone dying after contact with backyard poultry and wild birds, and with another severe case involving a teen in Canada. The varying genotypes and levels of illness indicate the capability of the virus to adapt and change.

Studies have shown that some people with H5N1 experience few or no symptoms. They could be shedding the virus and giving it more opportunities to mutate. As a result, we are essentially doing an experiment, and the more times we flip the coin, the greater the chance of, so to speak, getting five heads in a row, which, in this case, means human-to-human transmission or a more consistently severe illness.

What is the likelihood of human-to-human transmission? Do you see signs that point to that?

We've seen sustained animal-to-animal transmission, which raises concerns about the adaptability of the virus. Dairy cows keep getting infected and transmitting it, and potentially, the virus could be [jumping] from cows to birds and back to cows again. We're not 100% sure. But the more opportunities H5N1 has to mutate and change, the more possible it becomes for human-to-human transmission, since mutation is a hallmark of influenza viruses.

What would it take for H5N1 to turn into a pandemic?

One of the worst-case-scenarios is that we might have a person or an animal co-infected with H5N1 and another strain of influenza, such as the seasonal flu. This could create the perfect [breeding ground] for the virus to reassort in a way that gives H5N1 some of the characteristics that make it more transmissible in people. In other words, it could start spreading from one person to the next. That's the threshold we haven't yet identified as having crossed. If that occurs, then that's a big step for the virus—and one that raises its potential for becoming a pandemic.

How is the virus being tracked? Are the case numbers reported reliable, and is anything being done to bolster surveillance?

State governments typically take the lead on outbreaks, with support from federal authorities when they request it. Federal government agencies like the USDA and CDC are tracking and reporting cases, with the latest numbers indicating that 66 humans in 10 states and more than 900 herds of dairy cows in 16 states have contracted H5N1. But I think the numbers on both the human and animal side are the tip of the iceberg.

Recently, the USDA and FDA implemented measures to test bulk milk more often and in a more systematic way, which will help us identify some farms that may be infected but are not reported. That could be a whole group of cases that are being missed right now.

We also have surveillance in humans across the country based on health-care access. But many populations—an estimated 50% of farmworkers in the country are undocumented immigrants—don't have access to good health care and aren't part of that surveillance. So we could be missing those cases, too.

How can we stop the spread of H5N1?

Containing the virus isn't easy. For example, California, the leading dairy state, is experiencing a big outbreak right now, with the governor declaring a state of emergency. Dairy farms there are relatively close together and connected, in terms of personnel, equipment, and the movement of animals. But another concern is that farms [are located] in a migratory flyway, which is like a superhighway for migrating birds. Migratory waterfowl sometimes hang out near the manure [on dairy farms] and in close-by waterways, so that may be another route by which we're seeing spread.

Additionally, California's dairy farms are what we call "dry-lot dairies," or open-air dairy farms in which cows live in stalls with a roof but no sides. This makes it easy for birds to fly in and hang out in the stalls. Plus, birds are attracted to the grain [fed to cows], so they have reasons to go there. Complicating matters is that field mice, which are also attracted to the grain, are getting infected with H5N1, but we don't know yet whether cows can get the virus from mice. Studies are underway.

Right now, who is most at risk? And what precautions can the public take for themselves—and their pets?

Although the risk to the general public is low, there are things we can all do to avoid contracting the virus—and specific steps that backyard poultry owners and pet owners can take to stay safe. Make sure you avoid raw milk and raw milk products. Avoid raw or undercooked meat products, including eggs. Only use/consume pasteurized milk and pasteurized milk products. And do not touch or handle dead or dying birds and mammals.

If you have pets, know that different pet species are susceptible to the virus, including ferrets, dogs, and cats. I'm particularly concerned about cats because studies reveal a high mortality rate in house cats with H5N1—it can cause awful seizures and neurological problems, followed by death. Typically, house cats contract the virus from raw milk products or raw meat products. But cats can also contract the virus from wild birds or wild bird droppings. No one wants to hear this, but it's important to keep your cat indoors. Letting a cat outdoors is a demonstrated risk factor linked to H5N1 outbreaks in Europe and Colorado.

For dogs, keep them away from areas with migratory waterfowl. Some retrievers, for instance, spend time in waterways with migratory waterfowl. Bird droppings on the sides of ponds are another potential source of H5N1, and a place to avoid.

If your pets have an accidental exposure, use a pet-safe product to disinfect your pet, not something you would use to clean surfaces in your home. Consult your veterinarian if you have questions.

For backyard flock owners, it's important to understand that your chickens are at risk of H5N1. And if your chickens get sick, then you are at risk. I recommend using personal protective equipment when interacting with your chickens or handling their eggs. Wear a designated pair of boots inside your pen or coop. Change your clothes and wash your hands after visiting your pen or coop. Create an enclosure to prevent your chickens from roaming freely and being exposed to wild birds or wild-bird droppings. For additional guidance on preventive measures for farmers, pet owners, backyard flock owners, and the general public, see these resources from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Posted in Health

Tagged infectious disease