If you take a few steps south of Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus, you might hear water running. Sharp-eared visitors to the Baltimore Museum of Art's Sculpture Garden, located between Shaffer Hall and the headquarters for The Johns Hopkins News-Letter, have long reported the sound of water underneath their feet, tracing the noise back to a nondescript storm drain.

There are identical spots all over Charles Village and Remington. If you ask local artist Bruce Willen, he'll show some of them to you, keeping an eye out for cars as you stand listening in the middle of the street.

Then, if you shift your ear to Willen and ask him about the Sculpture Garden, he'll tell you that 125 years ago, there was no Baltimore Museum of Art. In fact, there was no Homewood campus either. The original location of Johns Hopkins University was further south in Mount Vernon.

Instead, there was Sumwalt Run.

Image caption: Sumwalt Run photographed from Charles Street, 1905

Image credit: National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Sumwalt Run was once a quiet creek that traced its way from Charles Village to the Jones Falls. A 1893 Baltimore Sun article described it as "a picturesque stream … graced with stately oaks and magnificent beech trees." The creek even passed through a small lake in Remington, which the Sumwalt Ice & Coal Company used to harvest ice.

Small streams like Sumwalt Run play a crucial role in their ecosystems, explains Ciaran Harman, an associate professor of landscape hydrology in the university's Department of Environmental Health and Engineering.

"Most of the rivers in the world are small streams," Harman says. "The big streams we think about carry lots of water, but in terms of the total length of streams on Earth, they're not that significant. The millions and billions of small streams are much more important."

Johns Hopkins University officially acquired Homewood in 1902. That same year, Baltimore hired Olmsted Brothers Co., a nationally renowned team of landscape architects, to design new parks for the city. The Olmsteds originally intended to preserve Sumwalt Run as much as possible, along with several of Baltimore's other stream valleys. But by the time the team turned their full attention to what would become Wyman Park, unchecked development had already buried portions of the creek beneath Charles Village. Back at the drawing board, Olmsted Brothers Co. then settled on a new idea: burying Sumwalt Run.

Sumwalt was moved underground between 1907 and 1914. Today, the stream takes a direct, rigid path under the Remington neighborhood, contained in a brick and concrete tunnel that can dip as far as 40 feet below ground.

The university's schools of Engineering and Arts and Sciences relocated to Homewood in 1914 and 1916, respectively. By that point, there was little evidence that Sumwalt Run had ever existed.

Enter Bruce Willen. Last year, Willen unveiled Ghost Rivers, a 1.5-mile-long public art installation that "reveals" Sumwalt Run. Painted blue lines stretch across roads and sidewalks, inviting passersby to walk along the now-lost riverbed. Willen also offers guided tours for the especially curious.

"I got started on the project when I saw an antique map of Baltimore from the 1870s and it showed a stream running through Remington," Willen says. "I'm really just interested in history's hidden stories."

Ghost Rivers begins just south of Homewood in Wyman Park, where Sumwalt's disappearance is most keenly felt. Even now, over a century later, the lawn curves down into a valley, sloping toward where the stream lies buried. The tour then traces its way downstream, passing by informative signs that shine insight into the neighborhood's history, landscapes, and infrastructure.

"That's what makes [Balitimore] so cool," Willen says. "You have all these different layers of social systems, ecological systems, infrastructure systems, and they all combine and go through and talk to each other and weave together. This project was, for me, a really fun way to tie all those threads together."

Willen partnered with Homewood Museum in April to lead a walking tour for Johns Hopkins affiliates. There, students, staff, alumni, and community members gained new insights into their neighborhood's history and ecology.

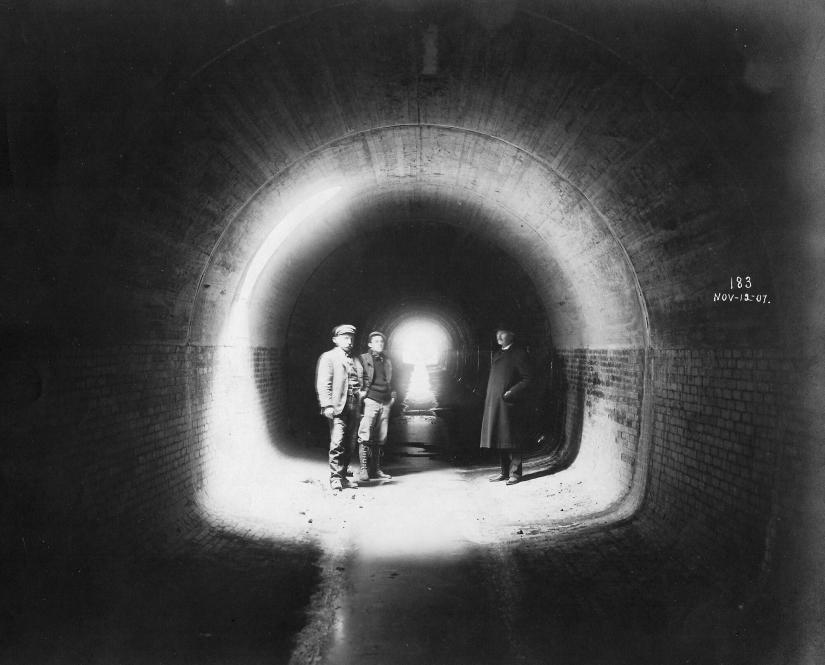

Image caption: A newly constructed portion of the Sumwalt Run tunnels, circa 1907.

Image credit: Maryland State Archives

Although burying a stream can have many advantages for a city, such as opening up new space for development, there are also many ecological drawbacks. According to Harman, beyond moving water from point A to point B, creeks provide homes to insects and other animals, filter out litter, and serve as biochemical reactors that process various nutrients.

"The ecosystem that lives in the bed of a stream does a lot of good stuff for us," Harman says. "When these streams get put underground, they're essentially put into pipes, and there is no ecosystem except for some slimy things that live in the dark."

Willen discusses such topics during his Ghost Rivers walking tour. For example, litter and chemicals usually caught by an above-ground stream shoot straight into Baltimore's harbor when it's moved underground. But with homes and businesses already built atop the tunnels, most of Sumwalt Run cannot be daylighted, or brought back aboveground. The Ghost Rivers walking tour raises a lot of questions: Was burying Sumwalt Run and other streams the right decision? If not, what does that mean for Baltimore?

According to Harman, these aren't uncommon questions for cities to have.

"Most cities have done this to some extent, where once small streams at the headwaters have become part of a stormwater drainage system," Harman says. "Baltimore is sort of interesting in that some relatively large rivers were put underground as well, with Jones Falls disappearing somewhere around Remington and only emerging again down at the Inner Harbor. I think that a lot of people aren't even aware of that, because you have to be driving around downtown and think, "There's a whole river back up there that we drive past. Where did that go?'"

Today, several branches of Sumwalt Run lay under the southern portion of Homewood campus. Each day, hundreds of students rush over them on their way from class to class, unaware of what lies directly beneath their feet.

But thanks to Willen's art installation, some students will notice strange blue lines on the sidewalks as they head home. Perhaps they'll walk away knowing just a little bit more about their city.

"What's important about the project is trying to understand the landscape that we live in today," Willen says. "How we got here, why we got here, and what it might look like in the future."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Posted in Arts+Culture, Community

Tagged environmental science, history of baltimore, environmental health