This article was originally published by Dome in its May/June 2024 issue.

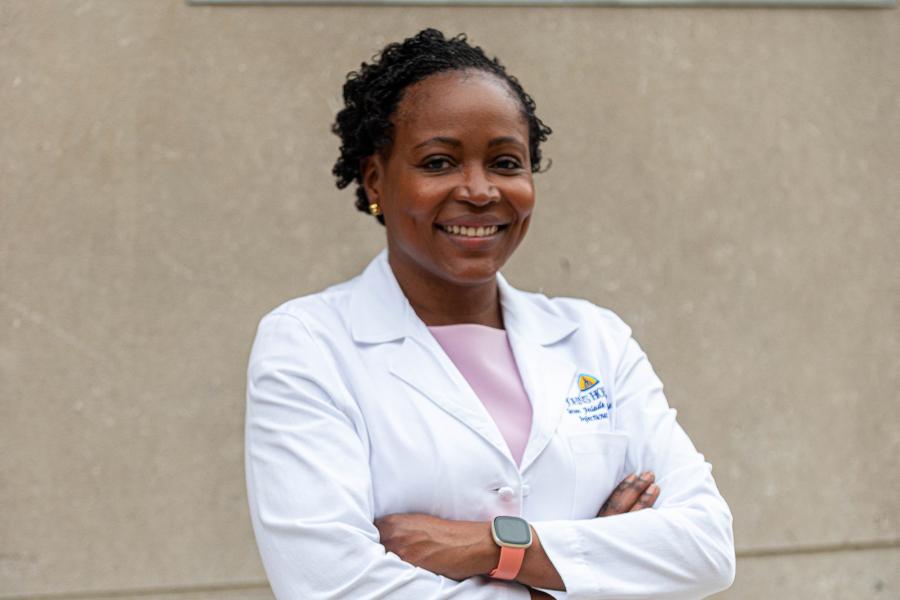

As a child growing up in Nigeria, Johns Hopkins physician Seun Falade-Nwulia felt distressed by the plight of female children and women in her society.

"Over and over again, I could see how girls and mothers had so little power. There were so few expectations of what they could achieve or what they were expected to contribute," says the associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "That has always stayed with me. I've always been drawn to those who are marginalized."

As an infectious diseases specialist, that concern has come to mean treating people, often underserved, who struggle with treatments for HIV and hepatitis C while also battling substance use disorders.

"I was in medical school at a time when HIV was killing people, and I wanted to be part of addressing that emergency," Falade-Nwulia remembers. "By the time I was finishing my fellowship at Hopkins in infectious diseases, we had available to us very effective medications or tools to both prevent and treat HIV and hepatitis infections."

While serving as medical director of the Baltimore City Health Department HIV early intervention initiative program, she came to recognize a major flaw in the care system. Not only were patients with "competing health priorities" — such as injection drug use — expected to visit a provider at one hospital or clinic, but they were also referred to additional locations to receive treatment for their infectious disease, substance use and mental health.

However multiple barriers such as homelessness, unemployment, lack of transportation and fear of stigmatization often prevented them from going.

"People who use injection drugs are at risk for infectious diseases, and when they get one, they have worse outcomes," Falade-Nwulia says. "We have the tools to not only prevent, but also treat these infections when they occur, but we're not doing a good job of connecting them to the patients."

Funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Institutes of Health has enabled Falade-Nwulia and her research team to study the effectiveness of integrated approaches for substance use, mental health, HIV and hepatitis C care for people who use drugs to increase access to the care they need.

Her work includes integrating hepatitis C treatment into various settings, including public health clinics, opioid treatment programs and syringe service programs. At the same time, she has expanded substance use disorder treatment in infectious disease care settings.

As director of the Center for Substance Use & Infectious Disease Care Integration at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Falade-Nwulia works to ensure that systems are in place for patients to receive the carefully coordinated care they require.

"The cornerstone of all the work I do is: How do we meet patients where they are? And also, How do we increase our understanding of what the patient is going through and work that into our approach to providing care?"

One important way is by recruiting state-certified peer recovery specialists to become part of the health care team. "A big part of what I do is to incorporate people with lived experience into the solution by eliciting their thoughts on what would make our approach better and then working with them to implement these approaches."

Peer counselors not only help patients navigate the care system, she says, but can also leverage their own personal experiences to support patients in identifying and overcoming barriers that impede care access and engagement.

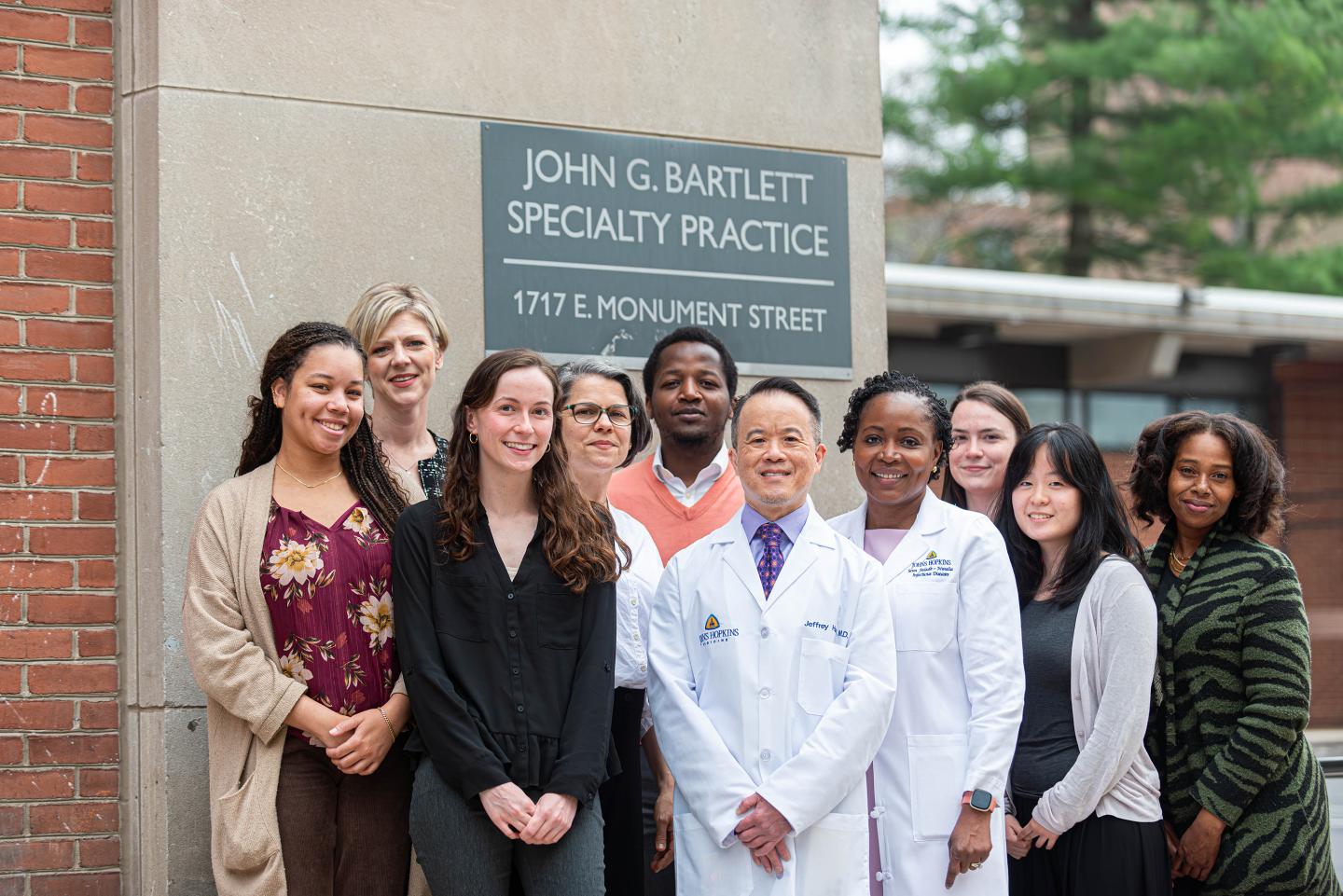

Image caption: Center for Substance Use and Infectious Disease Care Integration Faculty & Staff, from left: Annice Brown, Courtney Weglein, Meredith Gamble, Tracy Agee, Tarfa Verinumbe, Jeffrey Hsu, Seun Falade-Nwulia, Maria Latimer, Grace (ye Eun) Lee, Khristina Smith

Image credit: James Trudeau

In the Johns Hopkins John G. Bartlett Specialty Practice clinic for infectious disease care, people living with HIV can receive medications and treatment for substance use disorder as well as for HIV and hepatitis C, while also benefiting from psychiatric care and recovery support services.

"It's been amazing, the progress that we've made," says clinic psychiatrist Jeffrey Hsu, who began working with the mental health issues of patients with HIV in the hospital's Moore Clinic in 1999. Since that clinic became the Bartlett practice in 2017, he has been part of a multidisciplinary team that also treats substance use disorders.

"Fifteen years ago, many people would fall through the gaps when we referred them to outpatient methadone centers or to the Johns Hopkins Broadway Center for Addiction. Using this on-site integrated approach, we've been able to capture most of the patients in our clinic who have SUDs and provide some level of support for them."

According to a report published in the International Journal for Drug Policy, the innovative effort is succeeding.

"During the pandemic, when overdoses and anxiety rates were increasing, our patients were supported to reduce their substance use and lower their anxiety," Falade-Nwulia says. The integrated program also led more patients to adhere to their HIV and hepatitis C treatments.

When patients were asked to name the most impactful part of the program, many answered "Knowing that someone cares."

"That's really what every human being wants, right?" Falade-Nwulia says, "It seems simple, but it's actually very complex because you have to change not only the way care is delivered but also how to fund additional resources required in the health system in order to implement simple interventions such as peer support."

Her current study uses a structured approach to integrating mental health and substance use disorder care into the Johns Hopkins HIV clinic, and she will assess its effectiveness through a randomized control trial. The goal, she says, is to create a road map for others to follow.

Posted in Health

Tagged infectious disease, substance abuse