The Johns Hopkins Changemakers Profile is a monthly feature spotlighting the impact of Johns Hopkins alumni in positions of influence in Washington, D.C., policymaking circles.

Since eighth grade, Jacqueline Hackett knew what she wanted to be when she grew up. In fact, by her senior year in a suburban Philadelphia high school in 2004, Hackett was already more grown up than many of the adults in her life.

She was a D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Educator) mentor for elementary school students and a high school leader for two organizations focused on preventing youth drug use—Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD) and Youth To Youth. As a senior at her Harleysville, Pennsylvania, high school, Hackett testified before a congressional committee examining possible policy solutions for preventing underage drinking.

But Hackett knew more than what she wanted to do with her life. She knew where she wanted to do it.

"I wrote my college entrance essay on wanting to work on drug prevention policy in the White House," said Hackett, 37.

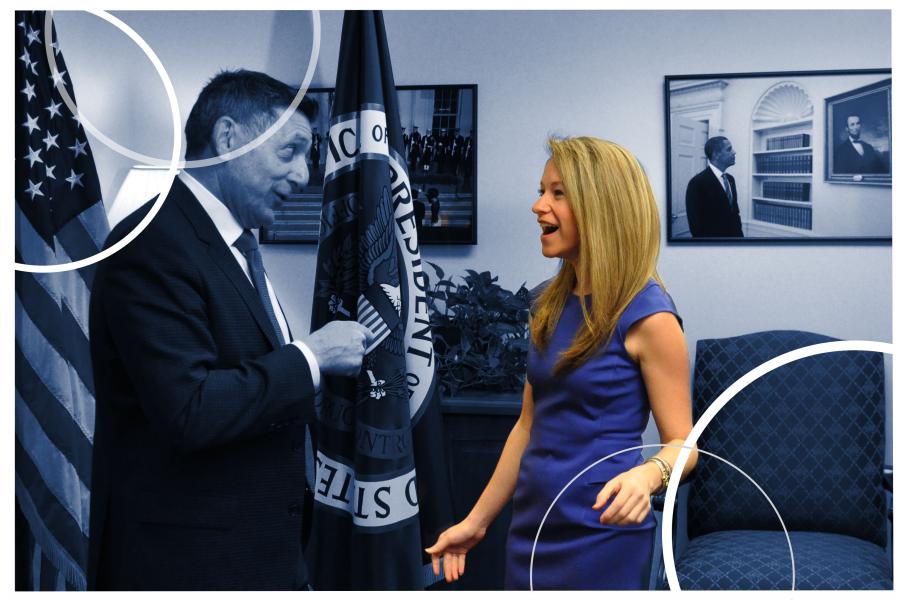

Occupation: Deputy Chief of Staff, White House Office of National Drug Control Policy

Age: 37

Hometown: Harleysville, Pennsylvania

Education: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's Bloomberg American Health Initiative, DrPH student, current; Master of Public Health, 2019. George Washington University, BA in political science and human services, 2008; MA in public policy, 2010.

Today, Hackett is the deputy chief of staff for the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, an executive office of the U.S. president where she has worked since 2011.

"I got involved in addiction policy and drug prevention in junior high school," she said. Thanks to mentors who explained a potential career path in drug policy, Hackett has never looked back.

She graduated in 2008 from George Washington University with a bachelor's degree in two majors—political science and human services—before earning a full-ride scholarship and completing a public policy master's degree two years later at the Washington, D.C., college.

After a brief stint in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Hackett landed her dream job at the White House in 2011. She started as a policy analyst for the intergovernmental and public liaison's division of the drug control policy office before becoming its deputy director for policy two years later.

"I worked to engage governors, attorneys general, state and local elected officials, as well as nonprofits to understand the policy priorities of the administration," she said.

The Office of National Drug Control Policy employs about 75 people with a mix of career and political staff as well as individuals with life experiences with addiction. With responsibility for overseeing a budget of approximately $43 billion, the office coordinates the administration's strategy for addressing addiction and the overdose epidemic across 19 federal agencies. As deputy chief of staff, Hackett reports to the "drug czar," who reports directly to the president.

"We have people who have dedicated their entire lives to working on drug control policy, and we have individuals with lived experiences and political teams that know the pulse of the political will and how to get policy moving based on what is happening with current events," she said.

She has worked for both Democratic and Republican administrations at a time when the opioid overdose crisis has turned addiction into a critical policy issue that transcends partisan differences.

"Governors in red and blue states both accept our phone calls regularly, and I don't think that happens with every policy," she said. "But when you have 109,000 people dying a year to overdose, people on both sides of the aisle realize we have to collaborate."

In 2017 Hackett entered the Bloomberg School of Public Health's master's degree program as a part-time student. Courses were primarily online, but she has also commuted by MARC train to get to Baltimore for an evening class once a week.

"Connecting with the faculty at Hopkins in person is worth its weight in gold," she said.

Hackett said harm reduction was gaining prevalence in policy circles as she began her studies and that she was "really lucky" to have worked closely at Hopkins with two leading experts in this area, Susan Sherman and Sean Allen.

"Both are nationally renowned for their dedication to making sure there is research and data to clarify any misconceptions about harm reduction," she said.

Harm reduction is an evidence-based approach to lower the risk of fatal or dire consequences for people who use drugs by equipping them with, for example, clean syringes and naloxone, a medication that can reverse overdoses.

She said one of the most valuable aspects of her education was learning how to understand and interpret raw public health data and evidence rather than just relying on the data team's findings.

"We have to use the data to drive what we're choosing to work on," she said.

Her master's thesis examined ways states could work to increase access to addiction resources, including peer counseling that has proven highly effective at helping people with substance use disorders. Many such peers were leaving state programs because of bureaucratic roadblocks such as rules that forbid agencies from paying peers with convictions, including for drug possession.

"We're learning so much about how important it is to have peers involved in the recovery process," she said. But their efforts must be compensated, she said. The current White House National Drug Control Strategy calls for expanding what is called Peer Recovery Support Services, or PRSS. "Sustainable financing for PRSS is indispensable," the strategy states.

In 2019, Hackett graduated from Johns Hopkins with a master's in public health and also completed certificate programs in public health advocacy and health communication. That same year she was named as a doctoral fellow by the Bloomberg American Health Initiative, whose director, Joshua Sharfstein, serves as her advisor.

"Jacqueline Hackett is an extraordinary public servant, with boundless energy and curiosity, a rock-solid commitment to the cause of saving lives from addiction, and an extraordinary optimism about what we can do better," said Sharfstein, who is also vice dean for public health practice and community engagement. "We're so proud to have her as a doctoral student and fellow and even more proud of what she does for the nation every day."

Hackett chose Johns Hopkins for her doctoral studies because it emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach that considers stability in housing, finances, health, and community when addressing addiction and overdoses.

Hackett, who also commutes from the White House to Baltimore to teach a graduate level course in health advocacy, said such a curriculum is "really unique" compared to other programs that take a narrower approach.

"Johns Hopkins forces you to look at public health holistically," said Hackett, whose dissertation will focus on improving access to naloxone, the life-saving medication for treating overdoses.

She is optimistic that the work of her office over her nearly two decades there has helped to diminish negative stigmas about addiction.

"People aren't scared to talk about their addictions," she said. "Since I started working in this issue area, people have become more understanding that addiction is a disease, that it's treatable, and that it is important to get the right care to people when they need it.

"We're seeing a flattening in the overdose death rate and that's because people are coming together, getting creative, and putting aside partisanship and other differences to make sure we see results," she added.

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged addiction, opioids, drug policy