- Name

- Johns Hopkins Media Relations

- jhunews@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9009

It may look like a simple contraption of nylon straps, molded polycarbonate strips, and foam padding, but to a local artist, it represents so much more: a voice, the ability to communicate thoughts and ideas, and freedom of expression.

"Art gives me a way to express myself without anybody interpreting for me," says Dan Keplinger, whose severe cerebral palsy prevents him from both speaking intelligibly and from using his hands to create the art that is his living and lifeblood.

Video credit: Roy Henry/Johns Hopkins University

Instead, his stylus and paintbrushes are affixed to a carbon-fiber rod mounted on a "crown" strapped to his head and under his chin, allowing him to use head movements to type messages on a computer and to create bold impressionist figurative works of art that have been exhibited in shows from New York and Washington, D.C. to Chicago and San Francisco.

Though Keplinger has used a similar device to paint, draw, and communicate since he discovered his prodigious talent in an art room at Parkville High School in the 1990s, the current version—which includes high-tech features aimed at enhancing its ergonomics and functionality—was created by a team of Johns Hopkins engineering students who are part of the university's Volunteers for Medical Engineering group.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

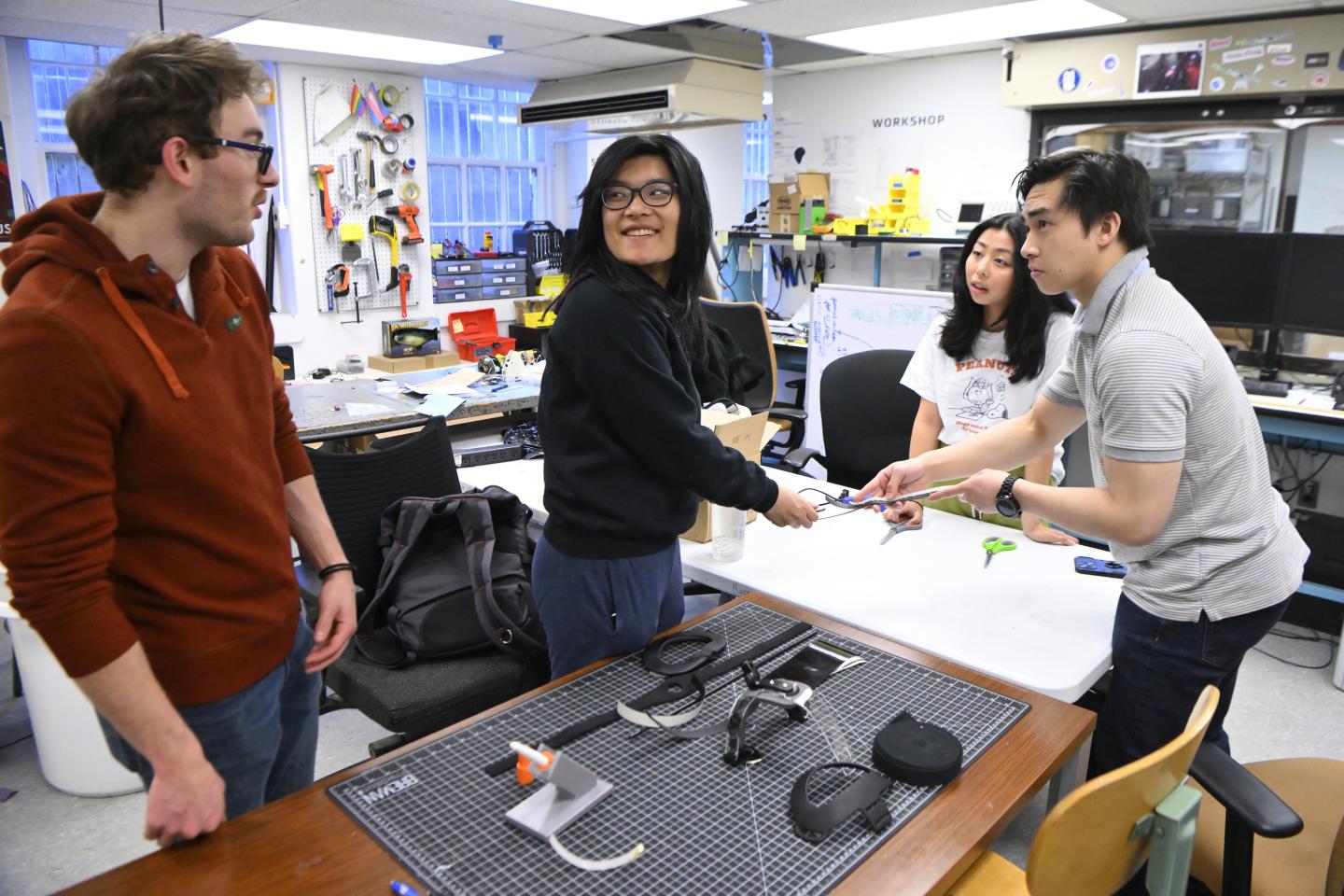

Led by senior mechanical engineering student Roberto Flores, VME members work with the Image Center of Maryland, a non-profit that pairs area residents dealing with disability challenges with volunteer engineers who create devices aimed at enhancing their independence.

"Dan's crown is one of three projects we tackled this year," said Flores. "It had major issues after years of being used for hours a day, and we provided some improvements."

Those upgrades included not only making the crown more durable and comfortable—the chin strap was so loose that the artist had work with his mouth open, so his lower jaw held it in place—but also customizing it to hold the stylus required for use with a touchscreen. When the team first met the artist, his stylus was attached with paint-splattered masking tape.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Keplinger asked for the ability to easily add (or remove) a pencil eraser to the stylus tip so he could shift between creating art and typing on his keyboard. (Typing sans tip could damage the stylus.)

"Before, he would try to use his hands to hold the eraser and move his head to manipulate the stylus to get it on the end. Sometimes, it would fall, and he couldn't retrieve it," says team member Melody Lei, a senior mechanical engineering major and project lead.

The team's solution was to create a 3D-printed plastic base that is mounted on the artist's desk and holds the eraser. Keplinger uses his head to maneuver the stylus into the base, snapping the eraser on and off the end as needed.

"Working with the students let me see new ways to do things, and the new crown will make my life a bit easier," says the artist, whose inspirational life story was the subject of King Gimp, a documentary that won an Oscar for "Best Short Subject" in 2000.

JHU VME team members on the project include Conor Allan, Tunde Ayodeji; Claire Borden; Alexis Diaz; Grace Huang; Nick Llaurado; Elaine Nagahara; Catherine Pollard; Delphine Tan; Alex Tinana; and Daniel Wang.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University