- Name

- Johns Hopkins Media Relations

- jhunews@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9009

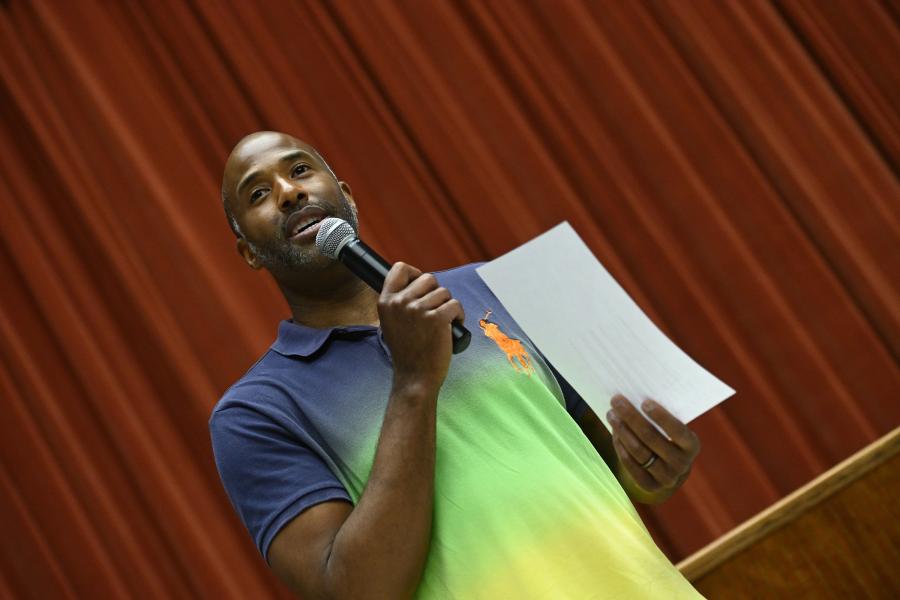

In 2015, Lionel Foster received an honor treasured by Baltimore City College graduates: an invitation to be inducted into the high school's alumni hall of fame. Foster accepted the recognition from his alma mater with great pride, but also with the sinking feeling that the strides that he'd made in journalism and nonprofit communications didn't measure up to the achievements of his fellow inductees.

At the time, Foster, who earned his bachelor's degree in Writing Seminars from Johns Hopkins University in 2002, was a communications manager at the Urban Institute, a research organization in Washington, D.C., that provides data and evidence to help advance upward mobility and equity. He had also worked in public service journalism, dedicated to highlighting economic and racial inequalities for outlets like the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore City Paper, and the Urbanite. Even so, Foster felt compelled to do more, and with his induction speech he launched the Baldwin Prize, an annual essay-writing competition for Baltimore City College students. Foster saw the contest as an opportunity to make a personal commitment to community service built on his love for the art of storytelling.

A cornerstone experience

Baltimore City College alums say attending the school is a cornerstone experience comprised of three critical components: academic rigor, school pride, and exceptional opportunities for students to flourish. For Foster, "City was a combination of a safe space—a place that was physically safe, but also a place where I was challenged intellectually." Among the many opportunities that Foster was afforded, he credits City College for honing and developing his innate love of writing.

"I give credit to City, especially because I became a journalist," he says. "It was at City where I was really taught how to write. It felt like really smart and caring people were teaching me what I now know to be the basics, but it also felt like secrets to learning how to do things well."

Image caption: City College students clap during the 2022 Baldwin Prize award ceremony.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

During his senior year at City, Foster was presented with what he calls an opportunity of a lifetime: a chance to utilize the curiosity about the world he acquired at City College to explore life and gain perspective abroad as an exchange student in Germany. "In Germany, there was something incredibly revelatory and liberating about being so young—I was 17 when I left—getting to experience a different culture, having people see me in a different light, and most importantly having the vantage point of being able to see myself in a different light," he says.

Foster says he had a similar experience when he went to Hopkins.

"I stayed local for college, but in some ways when I left Baltimore and the country for my senior year of high school, it felt as if I left the world," Foster says. "But coming to Hopkins, it felt as if the rest of the world came to me." After earning his bachelor's degree from Hopkins in 2002, Foster spent three years in London for graduate school. "From the ages of 17 to 25, I spent half of my life abroad," he says. "It was fantastic for me because it was those experiences and exposure to other ways of being and living that fueled my work in Baltimore. I've seen the ways things can and should be and I want that for my people."

From two essays to thousands

That revelation followed Foster in the early stages of young adulthood and led him to a career in public service journalism and the founding of the Baldwin Prize.

Named to honor the legacy of American writer James Baldwin, the Baldwin Prize was founded in 2015 as an essay writing competition for ninth grade students at Baltimore City College. Students who entered the competition were judged according to their ability to respond to that year's prompt, which asked students to explore a truth about themselves that is gravely under-appreciated. That year, only two students entered the competition. Since its founding, the Baldwin Prize would morph into more than just an essay writing competition for underclassmen. It would become a part of the curriculum.

"We really struggled to get students to compete in the Baldwin Prize our first year," says Amy Sampson, head of the English department. "We realized that students, especially because we were aiming it at underclassmen, just needed a lot more support. City students are juggling a really heavy workload so to add anything extracurricular on top of their academics was just asking a lot."

After integrating the contest into the core curriculum for ninth graders plus one 12th grade class, the essay competition would go on to generate thousands of essay submissions with the rigorous support of hundreds of volunteer writing consultants and judges. The 2022 contest netted more than 300 essay submissions.

"I initially envisioned it as an add-on or an extracurricular opportunity, but it's become quite a core facet of our 9th grade curriculum," Sampson says. "And it's something that we all feel really proud of. When I talk about some of the things that make City unique and I talk about reading and writing at City, I always point to the Baldwin Prize because it diversifies the type of writing our students can participate in."

Image caption: More than 300 City College students submitted interviews and essays on the theme of reconnection for the 2022 Baldwin Prize contest. The finalists' essays are available to read online at the Baldwin Prize website.

Image credit: will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Writing on deadline

From September through October, Foster workshops and refines the essay prompt idea with teachers in the English department. In January, he goes to the school to present the opportunity to the participating classes. This year, both the ninth- and 12th-graders were asked to focus on the theme of reconnection and were required to interview someone they know or would like to know better—while the younger students were required to write about their interviewee, the upperclassmen could choose to write a first-person essay instead.

In February each year, professional writers work with students as writing consultants and assist with developing student essays. There have been as many as 50 professional writers working with students either in small groups or one-on-one. Essays are due in March, when judges from at least four different countries have less than two weeks to read and score the essays.

This year's award ceremony took place May 20, was attended by more than 100 students, and celebrated the best crop of essays he has seen in the history of the Baldwin Prize, Foster says. This prompted organizers to honor 32 writers with cash prizes this year instead of following the past pattern of selecting just three winners each from the ninth and 12th grades. In an email to supporters, Foster gave a shoutout to three of his favorite 2022 essays: "The voice in Iche'la Carter's writing jumps off the page. Lillian Imhoff wrote about a house that helped build family ties. And Eli Weikert wrote about someone who lost a lot to the pandemic but is still grateful." The finalists' essays are available to read online at the Baldwin Prize website.

Planning for the future

In the Baldwin Prize's seventh year, Foster and other supporters envision the competition growing beyond just the essay. "Right now, the essay is the endpoint, but it really needs to be the beginning," says Foster, who now works in finance. "The Baldwin Prize must become a series of programs that support events and activities where the essay is the starting point." Foster notes that the Baldwin Prize prompt is typically the first time students tackle an assignment that looks like a personal statement required of many college application, so maybe they could lean into that. Or perhaps they could create an edited volume of the students' essays, turn the essays into podcast material or student films, or collaborate with other youth programs to inspire other young writers to find their voices. Foster would also like to be able to offer bigger prizes, he says: "The awards we offer are relatively small—between $100 and a few thousand dollars. It would be great to provide resources that will make a meaningful financial difference for someone trying to attend college."

New volunteers—from writing coaches to essay judges—are welcome to help move the prize forward, Foster says.

"Anyone that has any kind of experience getting their writing published—if you've written and have been edited—you are eligible to be a writing consultant and we would love to have you," he says. "We are also moving to a point where the Baldwin Prize will need an advisory board and there should be specific skills represented on that board—development/fundraising, website design, etc.—essentially people with expertise that can help me move the Baldwin Prize out of my bedroom and into an infrastructure that can be sustained is my call to action."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Alumni

Tagged lionel foster, baltimore city college