After historian Minkah Makalani finished writing his first book, he returned to London to explore some materials he'd stumbled across during his research there, planning to write an article about them. But when he brought his findings back to work on them in his African and African Diaspora Studies department at the University of Texas, his colleagues encouraged him to take the work in unplanned directions. The result is a book in progress about Trinidadian intellectual anticolonial activist C.L.R. James, which he says would likely not have happened in a different environment.

"They pushed me precisely at the point when I started to read more political theory," Makalani says of his colleagues. "I realized I had to do a whole lot more political theory, because I had to understand where James was coming from.

"Black Studies was an environment that explicitly thrived on not merely asking the questions that are appropriate to your discipline and your training, but asking the kinds of questions that are appropriate to the problem you're trying to understand, and that was a different kind of orientation. In that context, it became not, 'How do I approach this as a historian?' It became, 'What can I draw on, what resources are available, what methodologies are available, what intellectual orientations are out there that might help me understand and approach this question in a more fulsome way?'"

Named the director of the Johns Hopkins Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Center for Africana Studies last summer, Makalani envisions this kind of intellectual inspiration and synergism infusing departments, faculty, and students across Johns Hopkins and connecting with the city of Baltimore. Researchers in the history, English, political science, and other departments are already doing groundbreaking, essential work, he says, but Africana or Black Studies programs offer a specific style of intellectual freedom that sends scholars digging deeper than any one discipline allows and pursuing modes of inquiry outside as well as inside the academy.

"That's what Africana has the possibility of doing as Africana, as opposed to everyone doing it in particular locations on campus but it's dispersed," Makalani says. "It doesn't have the cumulative force of people working in conversation together and establishing new protocols for how we approach these questions, how we engage one another, and then what our graduate and undergraduate students learn, think about, and are exposed to."

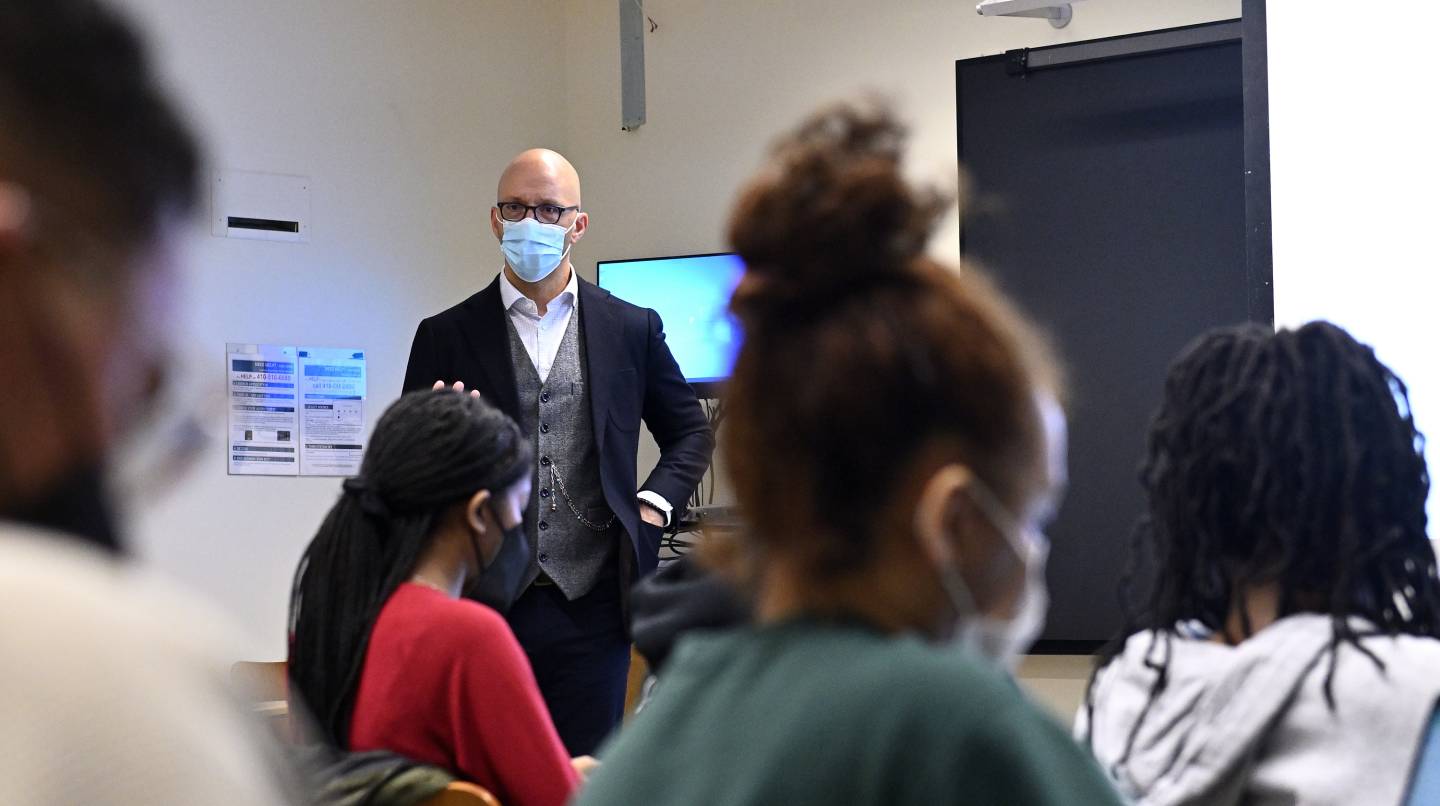

Image caption: Makalani teaches a spring 2022 course titled "Anti-Black Racism and Black Freedom Struggles: History, Theory, and Culture"

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Makalani, who grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, earned a bachelor's degree at the University of Missouri-Columbia, a master's at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, and a PhD at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He was assistant professor of history at Rutgers from 2004 to 2012, and assistant and then associate professor of history at the University of Texas-Austin until he arrived at Hopkins in 2021. At Texas, he also served as associate director and then director of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies.

At Hopkins, in addition to directing the center, Makalani is associate professor of history. He researches intellectual history, black internationalism, political theory, Caribbean independence, Black power, race, and racial identity and artistry. A current focus is what is known as the politically unimaginable—societies and structures beyond those we can imagine, because our imagination is limited by what we already know, he says.

"To go beyond almost any model, it's hard, and I think impossible, to say what it should look like. But in the act of saying what it should look like, and then trying to work it out, it's those things no one could account for that present the possibility of something closer to what we want in terms of true freedom, true equality, the end of all forms of oppression. That may be utopian, but it's probably best not to start out saying 'this is what the utopia should look like,' because that limits what we can think about," Makalani says.

What takes us beyond our imagination are acts of collaboration and interaction, which generate possibilities that haven't existed before. That collaboration and interaction happen especially in the making of democracy and the making of art—which are often one and the same, he says. He believes that the activist James was reaching toward questions and ideas that suggest art is not only a way toward the politically unimaginable, but actually can be the politically unimaginable, in the way that art worked as politics in ancient Athens, for example.

In his book about James as well as a book of essays he is completing, Makalani suggests that art and democracy are not only interwoven, but that art is often what we are trying to achieve with politics. This is especially true with dynamic art that evolves through interaction with its audience, the way hip-hop evolved alongside the B-boys and B-girls whose dancing galvanized the music's extended break beats.

"Maybe we need to look at art not as something that is outside of politics, or apart from politics, or that might become political, but look at art as what we are actually after with politics, with democracy, because we see it much more dynamically in the realm of art than we do in the realm of formal politics," he says. "That there's more there than just 'this is an example;' it might actually be the realm where we can pursue some of the very things we're talking about."

With the center, Makalani also plans to streamline the Africana studies major and create focal points for it by tapping into Hopkins' institutional strengths including public health, history, philosophy, political science, and sociology. And he wants to create a sense of community and intellectual exchange for both undergraduate and graduate students.

"The undergraduate population needs to feel some sense of community where they can be vulnerable with one another," he says. "Africana can provide a space for them to be a student at this dynamic institution and allow their minds to grow and move in any direction they want it to in the same way any other student might feel comfortable at a place like Hopkins. It can provide the safety to experiment and be daring and be young that students feel at HBCUs—to provide a little space for that kind of daring on the Hopkins campus—as well as challenge them intellectually, help them develop their skills, their thinking, prepare them for whatever career they want to go into.

"Graduate students are more intellectually focused; we want to facilitate that, push them in the best ways possible to do more maybe than they think they can do. We want to help them develop those aspects of their own intellect they already have, venture into new realms, make sure they are doing the best work they can do and thinking about the work they're doing in the most capacious ways."

When Makalani arrived in Baltimore, he was gratified to find Everyone's Place African Cultural Center on W. North Avenue, a bookstore that's been in place for more than 30 years presenting authors from Plato and Sophocles to Sonia Sanchez and Amiri Baraka. He describes the bookstore as a center of knowledge production and a concrete reminder that the community has always had an active relationship with scholarship and knowledge. Hopkins must shift its own framework to recognize that longstanding stewardship and expertise, he says.

"How do we alter what occurs here by taking that into account?" he asks. "It would be impossible to do a project on Black intellectual history, Black political thought, at any point in time if one stayed simply within the academy. Those are the kind of institutions that have sustained it."

So he envisions a relationship with Baltimore that encourages the sharing of resources and expertise and the growth of both entities. He wants to support community institutions in doing things they want to do, and for them to inform the work at Hopkins as well.

"How does the interaction help us think through Africana Studies in ways that are much more ethically and politically responsible to the charge of Africana Studies?" he asks.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged faculty news, africana studies