Peabody Institute Professor and Director of the Graduate Conducting Program Marin Alsop shared an anecdote from the podium before leading the Peabody Symphony Orchestra through Mahler's Symphony No. 1 in D major, Titan, in 2017. The previous year she had given a master class at the Lucerne Festival, where an older woman attendee asked profoundly thoughtful questions. "She was chatting with me," Alsop says during a Zoom interview from Linz, Austria. "And I thought, This woman really knows a lot about conducting—who is she?"

A bystander told her it was Sylvia Caduff, a Swiss conductor who in 1966 was hired as Leonard Bernstein's assistant at the New York Philharmonic and became the first woman to conduct that orchestra. In the 1970s, Caduff was named principal conductor of a German orchestra, the first woman to hold that position.

Alsop—the child of working New York City classical musicians who was told she couldn't be a conductor because she was a girl; who has throughout her career enthused about the impact her eventual mentor Bernstein had on her life; who had to shatter classical music's glass ceilings throughout her own career en route to being named the first woman to lead a major American orchestra when she became the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra's music director in 2007; who's matured into a stirring advocate for disrupting the performing arts' homogeneity through efforts such as OrchKids, the music-education-as-social-change program she started with the BSO in 2008; a woman whose many "firsts" can't fit into one article—had never, ever heard of her.

That confession earned a knowing audience laugh in 2017. But it also spotlights what makes The Conductor—the documentary about Alsop directed by Johns Hopkins Professor of Media Studies Bernadette Wegenstein—so potent. "It made me realize," Alsop says, "that if I didn't know [Caduff] was the first woman to conduct the New York Phil, what's going on with women's stories, you know?"

Following a number of film festival screenings, five documentary awards, and a brief theatrical run earlier this year, The Conductor is streaming through April 22 as part of the PBS Great Performances series. Wegenstein and producer Annette Porter, director of the Saul Zaentz Innovation Fund at Johns Hopkins, were the ideal filmmaking team to cultivate The Conductor into an engrossing, lyrical documentary. Both have forged careers exploring underrepresented stories—Porter with her Nylon Films production company, Wegenstein in a growing body of documentary films and interdisciplinary scholarship—and they put together a lean team to follow Alsop over the course of a few years as she worked with students, musicians, and orchestras in the U.S., Brazil, and Austria.

"Part of what we tried to show was that Marin didn't have a straightforward journey to become a conductor and that it cost a lot," Porter says. "The journeys for people who achieve firsts are hard, and we wanted to make sure that we showed the challenges faced by a kid with a euphoric dream who ran into walls and picked herself up again."

Image credit: Courtesy of The Conductor

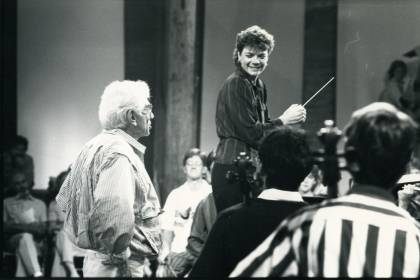

The Conductor capably delivers that story. Wegenstein and her co-writer and editor Stefan Fauland knit archival and original footage together to follow Alsop's life from an Upper West Side basement apartment, where her violinist and cellist parents hoped she'd take to the piano so they could form a string trio (Alsop hated the piano and gravitated to violin), to Juilliard, where she was repeatedly rejected for conductor training. In 1981, she formed an all-women's swing band called String Fever while also working as a freelance violinist, playing a gig here and there. She had to create her own conducting opportunities with financial assistance from business executive Tomio Taki, who helped her start the Concordia Orchestra. And after numerous rejections, she earned a spot at a Tanglewood summer conducting workshop. There, she finally met the man who changed her life when she first saw him lead a Young People's Concert when she was a kid: Leonard Bernstein.

"He broke all the rules," Alsop says. She was 9 and already feeling restricted by classical music's rigidity: don't move, don't smile, don't talk, just don't. "I was always getting into trouble, and then I saw this guy who turned around and talked to you because he really likes this music. And when he conducted, his whole corpus was engaged and enthusiastic. I loved it—and I thought, OK, maybe I can do this classical music thing after all."

Austrian native Wegenstein sat in on Alsop's conducting classes for a year and hired Peabody graduate student Alexa Rinn to tutor her as she studied scores of the works Alsop conducts in the film. "I really tried to understand how they translate this music that they see into gestures, as it seemed to me that there was this kind of secret communication going on," Wegenstein says.

"Classical music is such a complex art, and we edited the music to interact with the mood of every scene and our character's feelings," Wegenstein says, remembering how she storyboarded sequences to musical cues. "A music expert like Marin is similarly complex—when she speaks, she's a little guarded, but I think the music that she sees and hears inside her head is her real self."

The Conductor doesn't condescend to explain what a conductor does so much as explore one woman's relationship with art that transcends language. "Conducting is a very odd profession because it's like philosophy, but more abstract," Alsop says. "You're not making any sound. You're literally not putting your hands on anything. Everything is about inspiration and motivation and information.

"I think that's one of the reasons I love conducting," she continues. "It's really a metaphor for who you are as a human being."

Also see

The Conductor movingly charts one artist's path toward excellence in an industry that unfortunately still can't see past gender. Over the winter, French conductor Nathalie Stutzmann was named the music director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra starting this fall, at which time she'll become the only woman leading a major American orchestra. "I finished my tenure at the Baltimore Symphony, and after 14 years there, I remain the only woman to have led a major American orchestra," Alsop says. "Now I'm gone, and there's no American woman leading a major American orchestra. I think that says something."

Posted in Arts+Culture