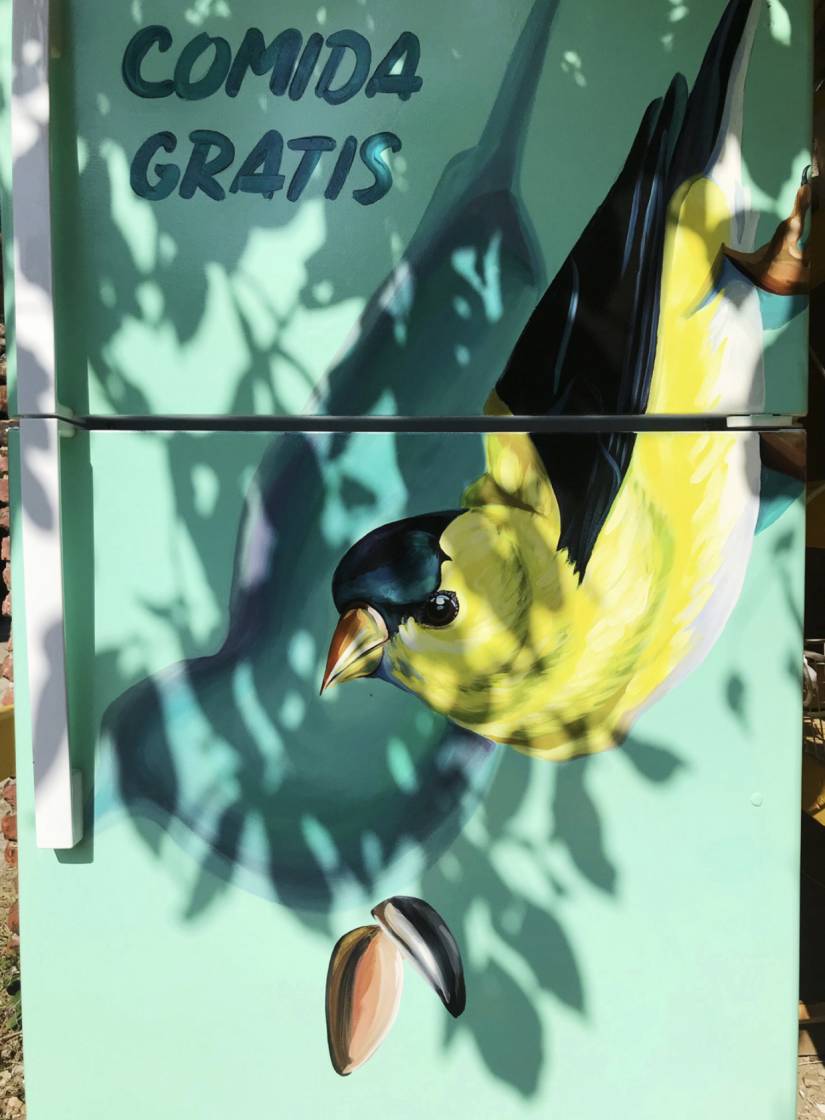

Beside a brick wall in Baltimore's Greenmount West neighborhood, a sea foam green refrigerator hums. A corrugated metal roof protects it from rain and snow. A goldfinch poised above two seeds is painted on the front of the refrigerator; above it are painted the words, "Free food. Comida gratis."

This is the Baltimore Community Fridge, a mutual aid organization envisioned and started by Clara Leverenz, A&S '21, during her senior year. Although Leverenz is now living and working in New York City, a cadre of volunteers keep the fridge—and an adjacent pantry—stocked with food, toiletries, and other necessities. Kale, spaghetti squash, and sweet potatoes from local farms have passed through the fridge in recent days. Cans of vegetables, rolls of toilet paper, toothpaste, menstrual supplies, and at-home COVID-19 test kits move through the pantry.

"For me, food has always been my love language," says Leverenz, 22. "I would always cook for my roommates. When the pandemic started in 2020, we began noticing exacerbated food insecurity issues and I wanted to do something about it."

Leverenz, a New York City native, heard from hometown friends about these community refrigerators popping up there and subsequently researched the model herself to create one in Baltimore. It's a simple way to move food and other goods from the hands of those who have a little extra to spare directly to neighbors and community members. She posted on Instagram to find others interested in volunteering and connected with Abbey Franklin, a 2021 graduate of the Maryland Institute College of Art. The two women found a donated refrigerator and, after a few months of false starts, a location about a mile and a half from the Homewood campus. In November 2020, the fridge opened behind 209 McAllister St., which is home to Blue Light Junction, a natural dye garden and color lab where founder Kenya Miles allows the fridge to be plugged into one of its electrical sockets. Right across the street is Hidden Harvest Farm, which provides fresh produce for the community fridge. Local artist Jessy DeSantis painted the goldfinch.

"It's all run by volunteers," says Leverenz. "We have volunteers who stop by every day to clean it out and volunteers who restock it a couple times a week. It's very grassroots."

One of those volunteers is Justine Bumpers, 31, a photographer who lives in Hampden. "I constantly feel very overwhelmed because there are so many people in need of help," she says. "The fridge felt like something that I could do consistently where I could directly help people."

Also see

Bumpers visits the fridge at least once a week, dropping off bagged snacks, granola bars, and single-serve meals. Many of the people who pick up food from the fridge are unhoused and don't have access to a stove or microwave, she says. Shortly before Thanksgiving, Bumpers raised funds on social media to purchase the ingredients for 36 vegetarian holiday meals. She and a friend cooked collard greens, stuffing, mashed potatoes, and mac and cheese, then packed them into single serve containers.

"Those went really quickly," she says. She was planning on cooking another large batch of meals with ham and sides before Christmas.

"I want people to remember that those who live on the street are human," says Bumpers. "Everyone deserves to eat, no matter what they have gone through."

Volunteers use social media to alert each other when the fridge is running low. They also chat with visitors to the fridge to get a sense of what community members need—say sandwiches or deodorant—and will put out a call for the requested items.

Leverenz, an anthropology and art history major who now works in a New York artist studio, keeps on top of the activity of the fridge from afar. She encourages friends who are still at Hopkins to stop by and help out. "You can message us on Instagram and find a time to volunteer," she says. "We just ask you to bring wipes and wipe down all the surfaces used a lot. We also need people to toss contributions that have gone bad in the adjacent compost and trashcan."

And for those who would like to help but are unable to come to the fridge in person, Leverenz welcomes donations via Venmo. These donations are used to buy food in bulk, upgrade the structure around the fridge, pay for electricity and compost services, and allow the volunteers to host community events.

Leverenz says that the best part of the project has been forging relationships that transcend boundaries of geography and socioeconomic status. "One thing I really appreciate is all the connections being made," she says. "During the height of the pandemic, you weren't meeting anyone new. The fridge has been a real connector."

Image caption: The latest iteration of the community fridge with goldfinch mural by local artist Jessy DeSantis.

Image credit: Photograph by Christina Calhoun

Image caption: Clara Leverenz painting the words "Baltimore Community Fridge" atop the yellow fridge structure in May 2021.

Image credit: Photograph courtesy of Clara Leverenz

Image caption: Clara Leverenz and Baltimore Community Fridge organizer Christina Calhoun hosting a Halloween 2021 pop-up at the fridge.

Image credit: Photograph courtesy of Clara Leverenz

Posted in Student Life, Community

Tagged community, baltimore community fridge