For decades, hosannas have been raised to Charles Herty and George Petrie for seeding the colossus in the South known as college football. Herty, a chemistry professor, was the first coach at the University of Georgia; Petrie, a historian, the first coach at Auburn University. Each organized the varsity football programs at his respective school, and their teams first played each other on Feb. 20, 1892, in Atlanta. Auburn, then called the Agricultural & Mechanical College of Alabama, won 10-0. But the score is a minor detail.

Not just a game, Georgia vs. Auburn is revered as the "Deep South's Oldest Rivalry." That rivalry was renewed for the 125th time on Oct. 3 in the 92,746-seat Sanford Stadium in Athens, Georgia—albeit at 20% to 25% capacity—and Georgia won 27-6.

In many ways, the infatuation with college football in the South—the 100,000-seat stadiums, the megamillion dollar athletic budgets, the dominance in national championships (14 of the past 15 title winners hail from Southern states)—flowed from that rain-soaked mud bath of a game in 1892 organized by two academics, who both attended Johns Hopkins to earn their doctoral degrees.

Yet, there remains a mystery around the relationship between Herty and Petrie (pronounced Pee-tree), and just how football entered their lives. A lot of details can get swept into history's dustbin over 130 years.

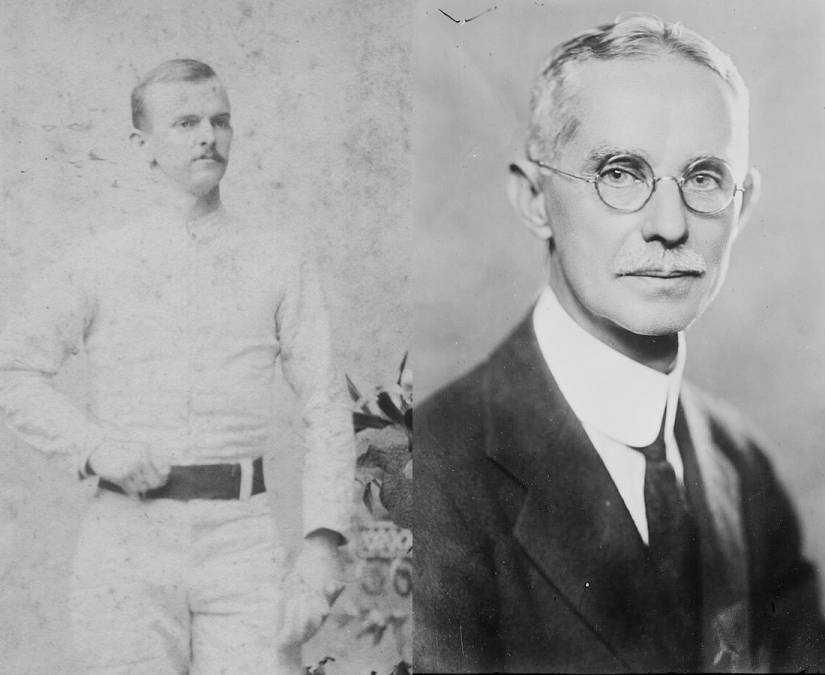

Image caption: George Petrie (left) in his football uniform and Charles Herty

Image credit: Auburn University Libraries Special Collections & Archives and the Library of Congress

Both were sons of the South, to be sure. Herty was born in Milledge?ville, Georgia, and attended the University of Georgia. Petrie was born in Montgomery, Alabama, and attended the University of Virginia. They were together on the Johns Hopkins campus—then located in downtown Baltimore along North Howard Street—in 1889 and 1890. Both were working on their doctorates, with Herty graduating in 1890 and Petrie in 1891. Herty lived on West Madison Street, Petrie on North Howard. Did they bump into each other on the street, recognize each other's distinct Southern drawl, and talk sports? Their courses of study were different—one a historian, the other a chemist—so it is doubtful they shared classroom space. Did they attend one of JHU's seven football games in 1889, or the one game in 1890, and make a plan to introduce pigskin to the "Cotton States"?

"They were graduate students at the same time and the student body was small and they lived near each other, but they were not close friends, not from what I could find," says Mike Jernigan, author of Auburn Man: The Life & Times of George Petrie.

In 147 boxes of Herty papers in the Emory University Library in Atlanta, not a trace of a relationship between the two men while at Johns Hopkins could be found, according to a researcher there. Jernigan, however, did find something gainful that illuminates Georgia vs. Auburn and the link back to Johns Hopkins.

Petrie's intention was to study languages at Hopkins when he enrolled in 1889, but he registered for a history class because he wanted to experience the seminar of Herbert Baxter Adams, who would become known as the founding father of the seminar method and of professional historians in the United States. Jernigan said it was because of Adams that Petrie became enthralled with history, a subject he had previously detested.

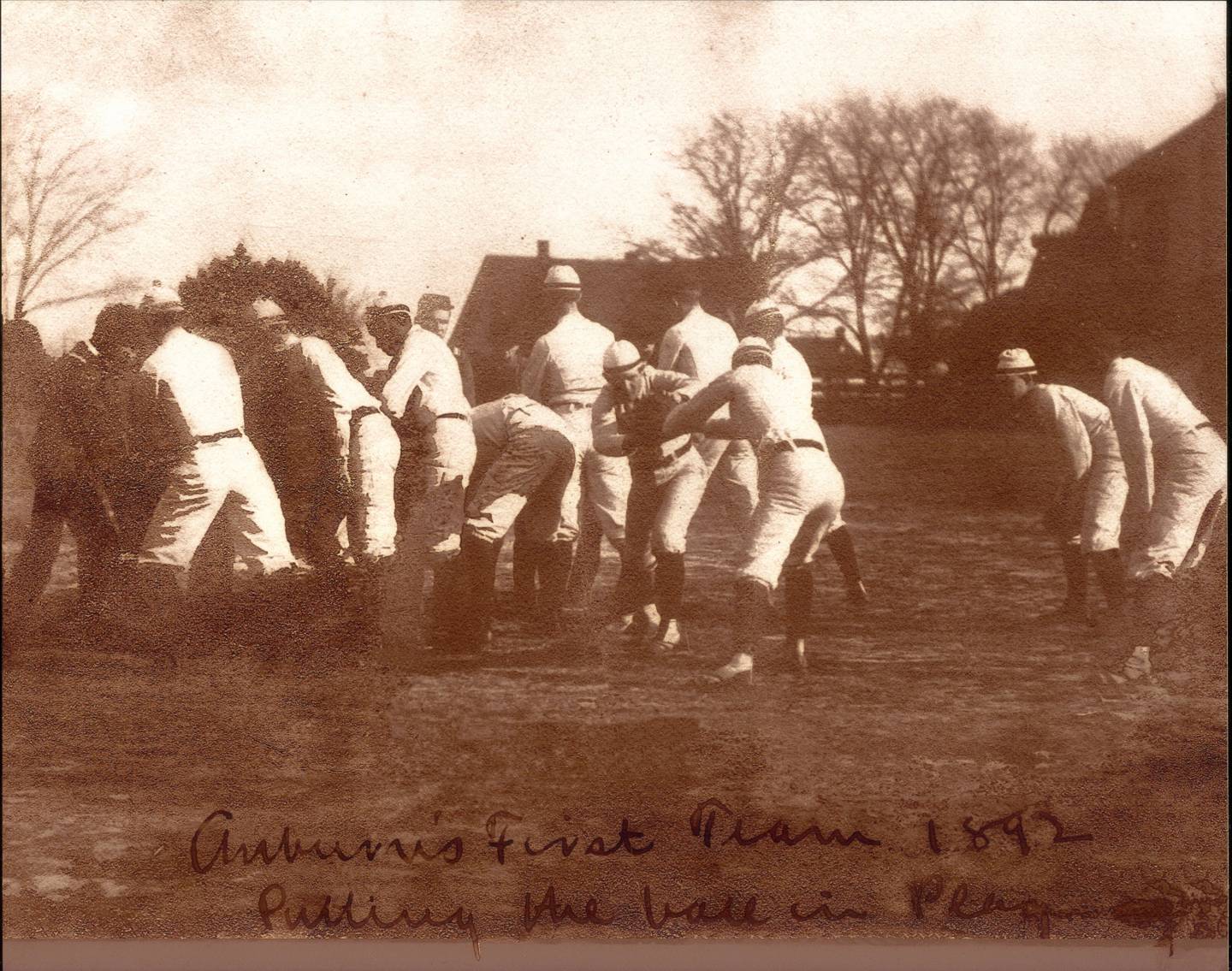

Image caption: The inscription on this photo reads "Auburn's First Team, 1892. Putting the ball in play."

Image credit: Auburn University Libraries Special Collections & Archives

Petrie would later take a history class from a visiting lecturer, Woodrow Wilson, who would become the 28th president of the United States. Wilson, who received a PhD from Hopkins in 1886, was regarded at the time as an authority on football. "Professor Wilson" coached football at Wesleyan in 1888 and 1889 and was, according to a former player on those teams, "a genius in the application of football strategy."

Petrie's relationship with Wilson goes deeper than that one class, however. Jernigan wrote in his book that Petrie's father, who lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, had come to know Wilson during his time studying law at the University of Virginia in 1879 and 1880. In Baltimore, Wilson's brother-in-law and Petrie lived in the same boarding house, and Wilson visited frequently, with football a likely topic of discussion.

Petrie wanted to stay at Hopkins after earning his PhD, Jernigan writes, but there were no faculty openings because of a budget crisis, so he took a job as professor of history and Latin at Auburn in the fall of 1891. A significant hire for the school, Petrie was the first person in the state of Alabama to earn a doctoral degree. He had gravitas, which might help explain how he was able to rally the cadets to the newer version of football.

When he arrived at Auburn, Petrie saw students playing "football" on a field in front of the administration building, though it was more akin to a soccer/rugby game, with players kicking the ball from one end of the field to the other.

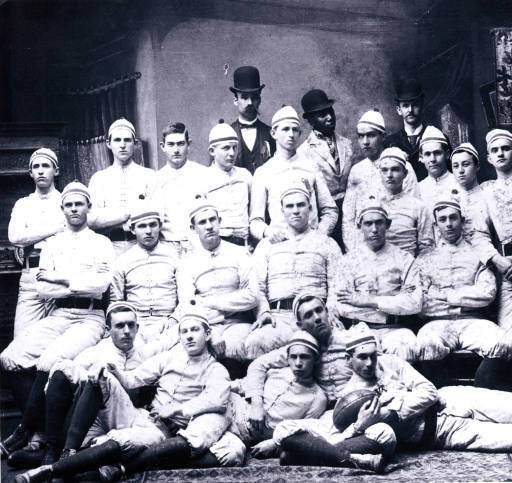

Petrie started to recruit the "huskiest" players and organize them to play a more modern game of football, such as the sort he might have witnessed up north at schools like Harvard, Yale, the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), and Johns Hopkins. Two of Petrie's top players at Auburn were not students, but professors. The others were students, who had to be taught the sport.

Image credit: Auburn University Libraries Special Collections & Archives

Meanwhile, Herty, who was 175 miles northeast in Athens, was busy putting together his own squad in the fall of 1891. On the first day of practice, according to multiple historical sources, he tossed a ball into the air and had students scrum for it. That was the tryout. Herty would do that 11 times to get his starting team. Whoever came up with the ball in the scrum made the cut. He went by "trainer," not coach.

The first game in the history of Georgia football was played January 30, 1892, against Mercer University in Athens. UGA won, 50-0. It was assumed that Petrie, building his Auburn squad for the 1892 season, knew that Georgia had a formidable team and communicated "Let's play" to Herty to set the stage for the historic game.

As it turns out, there's more to the story than that.

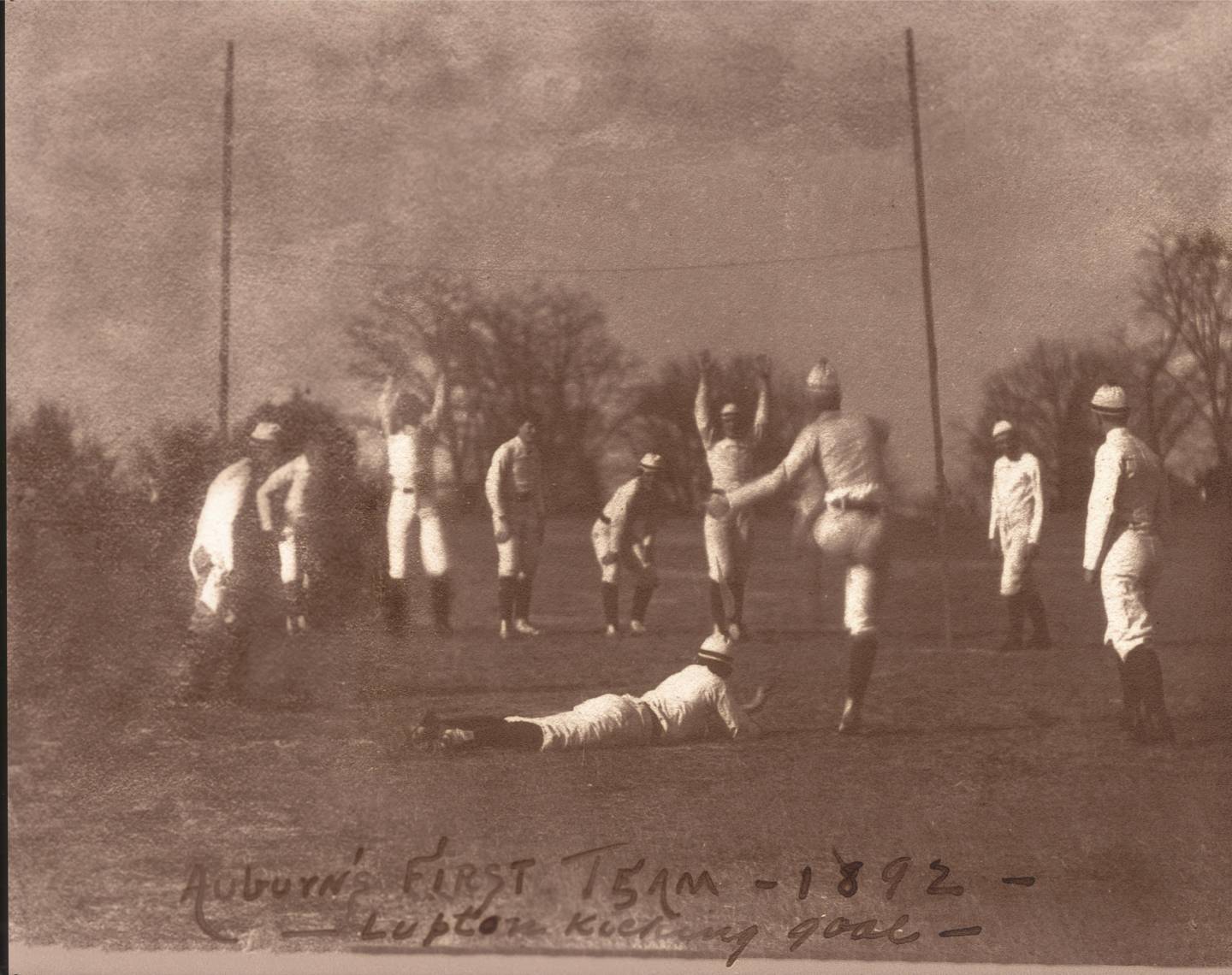

Few people in the South knew the rules of the Northern game, so John Kimball, an Auburn graduate who lived in Athens, had asked Petrie to come to Athens and "umpire" the Georgia-Mercer game. Instead, Petrie sent one of his players, Frank Lupton, to do the job, Jernigan writes. Soon after the thrashing of Mercer, Petrie issued, through Kimball, an invitation to Georgia to play Feb. 20 in Piedmont Park in Atlanta, part of a three-day weekend celebrating George Washington's birthday. Lupton, the Auburn player, no doubt provided the first scouting report in the history of Southern college football.

Image caption: The inscription on this photograph reads, "Auburn's First Team, 1892. Lupton kicking goal."

Image credit: Auburn University Libraries Special Collections & Archives

The day of the game, carriage space on one side of the field was $1. Adult tickets were 50 cents. Children paid 25 cents. The Atlanta Constitution said attendance for the 3:30 p.m. start was between 5,000 and 8,000, and gate receipts were $800. The fascination with this other style of football, and the pre-game coverage of the event in newspapers, drove the attendance.

It was chilly and raining, the kind of weather and subsequent marsh fit for a, well, goat.

The Auburn uniforms of white coat and blue hose were picked out by Petrie and stitched in Boston. The uniforms, which collectively cost Petrie $35.06 of his own money, according to Jernigan's book, became caked with mud as the game wore on. On the other side of the field, adorned in a black coat with the letters "UG" was the Georgia mascot, a goat named Sir William. (University of Georgia athletic teams did not adopt the nickname "Bulldogs" until 1920, at the suggestion of an Atlanta sportswriter.)

Both teams used as their offense the Flying V formation. After a scoreless "first inning" of 45 minutes, Auburn scored 10 points in the second inning. According to The Atlanta Constitution, fans stormed the field. The winning team, Auburn, triumphantly walked 3 miles back to their hotel downtown.

Jernigan has pages and pages in his book detailing the lead-up to the game, the game itself, and the aftermath. That there are documents galore is owing to the influence of Johns Hopkins University, he says. Adams, the school's history icon, preached to his students the value of "original research" and preserving documents. Jernigan says Petrie learned those lessons and saved a trove of documents and newspaper clippings on the Georgia-Auburn rivalry. Petrie himself wrote an account of the game for his hometown newspaper, The Montgomery Advertiser. He clipped out a copy and sent it to Woodrow Wilson.

Herty saved documents and scraps of his life, too, but the volumes in Emory University libraries were devoted to his life in business. Born in 1867, he was the only son of a Confederate veteran. He was also a child of the Reconstruction and saw the toll the Civil War had taken on the Cotton States. Herty was devoted to trying to industrialize the South through his passion, which was chemistry, not football.

In the book Crusading for Chemistry: The Professional Career of Charles Holmes Herty, author Germaine Reed wrote, "Charles Herty played a major role … to promote and popularize chemistry among every element in American society."

"He was not a pure chemist, or bench chemist," Reed says in an interview. "He was somebody who wanted to make science available to the average person and he had the ability to explain hard things in pedestrian terms. He was able to talk to the average person and I think that is how he was able to accomplish so much. He was a lobbyist, not a paid lobbyist but a communicator who was very connected politically."

It was Herty who developed the process for tapping the resin in pine trees that built the turpentine industry in the U.S. and saved thousands of trees. Herty's research into pulpwood in Savannah, Georgia, showed how pine trees could be used for the manufacture of newsprint. Reed wrote that Herty, who started the athletic program at Georgia, also helped grow the athletic department at the University of North Carolina by recruiting football and baseball coaches.

Herty also had a hand in the creation of college football's preeminent league of schools, the Southeastern Conference.

Concerned about the influence of "professionals," men who did not attend the school but showed up to play on game day, he helped organize a meeting in December 1894 in Atlanta of the top Southern football-playing schools: Vanderbilt, Sewanee, Auburn, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina. Johns Hopkins, located below the Mason-Dixon Line, was also part of the confab. They created the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, and Herty was elected secretary-treasurer.

The SIAA eventually seeded the Southern Conference, which grew to 23 schools. In 1932, the 13 schools south and west of the Appalachian Mountains split from the Southern Conference and became the SEC, which included Herty's school, UGA.

Reed wrote that Herty left the University of Georgia in 1901 following a dispute with the head of the Chemistry Department. Still, 28 years later, he was asked to return to the dedication of Sanford Stadium. In a sign of reverence for having coached the school's first football team, Herty is memorialized on campus today with the well-groomed Herty Field, the site of the first game with Mercer.

While Herty left academia in 1916, Petrie remained at Auburn as the head of the History Department and dean of the graduate school until he retired in 1942. He wrote the Auburn Creed in 1943. It remains a living document on the essence of Auburn and how students should conduct themselves. Petrie would also organize, and coach, the school's baseball team and arrange its first intercollegiate game.

The 1892 football season was the only season the two men coached. Herty went 1-1. Petrie was 2-2. In such a short period, it seems an exaggeration to say that Petrie and Herty could leave such an indelible mark. But they got there first and that, with their character and conduct, will forever distinguish them in the history of college football in the South.