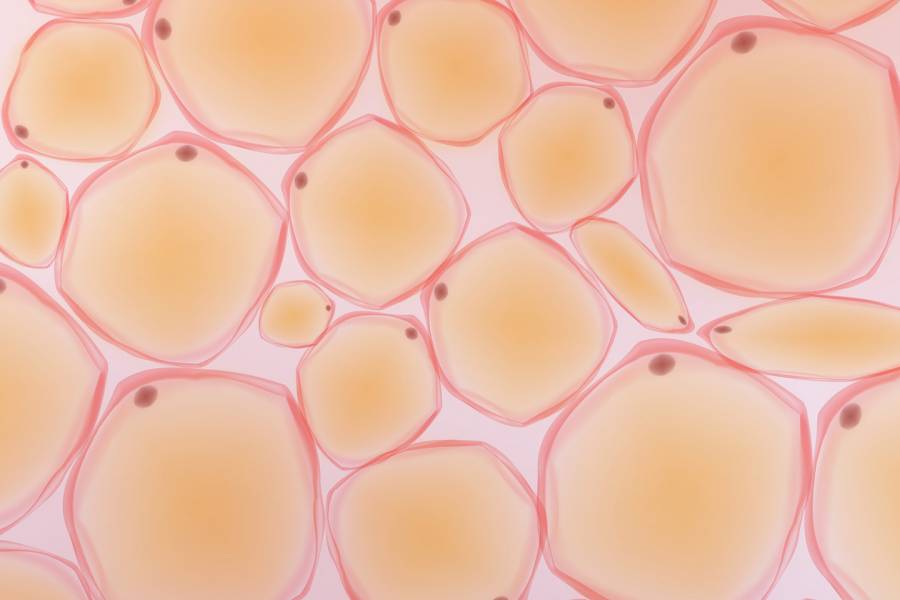

Toxic man-made chemicals that are absorbed into the body and stored in fat may be released into the bloodstream during the rapid fat loss that follows bariatric surgery, according to a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The finding points to the need for further research to understand the health effects of this potential toxicant exposure.

For the study, published online in Obesity, researchers examined 26 people undergoing bariatric weight-loss surgery and found evidence of post-surgery rises in the bloodstream levels of environmental toxicants that are known to be stored long term in fat, including polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, and polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, are a class of chemicals previously used in plastics, dyes, and electrical equipment. Although no longer commercially available, these toxins have been linked to cancers and disruption of the immune, reproductive, nervous, and endocrine systems, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Organochlorine pesticides have been shown to act as endocrine disrupting chemicals and the effects have been linked with hypertension and cardiovascular disorders. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers are PCB-like chemicals that can be inhaled or ingested, and although not directly linked to cancers, these toxins have been linked to the development of tumors in rat and mouse studies. Bans on the U.S. manufacture of PCBs and the organochlorine pesticide DDT took effect in 1979 and 1973, respectively.

"The fact that this increasingly popular type of surgery may be causing these compounds to be released into the bloodstream really challenges us to understand the potential health consequences," says study senior author John Groopman, a professor in the Bloomberg School.

About 16 million people in the U.S. are morbidly obese, defined as having a body mass index of 35 kg/m2. Morbid obesity confers a relatively high risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and many cancers. For almost three decades, the U.S. National Institutes of Health has recommended weight-loss surgeries called bariatric surgeries—including stomach stapling and gastric bypass procedures—for people who are morbidly obese and have serious obesity-related conditions such as diabetes, as well as for anyone with a BMI over 40. More than 200,000 bariatric surgeries are now performed in the country every year.

Although bariatric surgeries are known to have potential adverse side effects, including micronutrient deficiencies, the release of environmental toxicants from fat storage isn't one that has been studied before. Recently, though, Groopman and other researchers from the Bloomberg School and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine realized that as these surgeries were becoming common, and, since they involved rapid fat loss, they could potentially release toxicants stored in fat into the bloodstream of patients.

The researchers enrolled 27 patients who were morbidly obese and scheduled for surgery at the Johns Hopkins Center for Bariatric Surgery. Of these, 26 patients went through with the surgery and were included in the analysis. Each patient had a blood sample taken at the time of surgery and on four follow-up visits over six months. The analysis, aided by experts at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, focused on the bloodstream levels of 41 toxicants, including 24 PCB compounds and five organochlorine pesticides that were detectable in the initial samples. The researchers also classified the patients into two groups: those born before 1976, when most of these chemical compounds were still widely used, and those born after. The first group contained 17 people and the second group contained nine.

The results showed that the patients born before 1976 started the study with roughly 5 times higher serum levels of most of the PCBs, as well as higher levels of organochlorine pesticides, compared to the patients born after 1976. During the six months of weight loss after surgery—in which the patients lost an average of 23 percent of their initial weight, or nearly 30 kg each—both groups of patients tended to show increases in serum levels of fat-stored toxicants. For example, in the older patients, serum levels of most PCBs went up by 15 to 25 percent for every 10 kg of lost weight. The older patients, who started with higher baseline serum levels of most toxicants, and presumably had much greater fat stores of these compounds, tended to have higher rates of increases in serum levels per unit of lost weight, especially for PCBs.

The researchers note that studies with larger populations need to be done to verify the findings in this small-sample study. Further research, they add, could also determine if there are any biological effects, especially on sensitive, fat-rich organs such as the liver and brain, of the toxicant doses involved.

"There is remarkably little information in the literature that relates blood levels of these compounds to effects in tissues," says Groopman. "It would be great if we determine that it's not a problem, and it might turn out not to be. At the same time, the data might suggest that people should lose weight more slowly, or that we should somehow find ways to trap these compounds as they are released into the blood. We also need to recognize that the compounds released from the fat represent lifetime accumulation of toxicants, and we need to address these life course exposures to determine health risk."