Minutes after an infant is born, doctors must assess five key health metrics: heart rate, respiration, muscle tone, reflex response, and color. The assessment, called the Apgar Score, helps determine which babies are in need of immediate emergency attention.

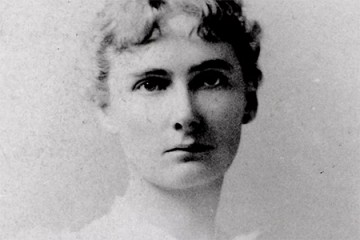

Image caption: Virginia Apgar

The Apgar Score, now the standard method for assessing infant health, was developed by Virginia Apgar, who earned a master's degree in public health from Johns Hopkins University in 1959.

Apgar was born in 1909 in New Jersey. Her father shared many scientific hobbies that may have sparked an early interest in science and becoming a doctor. Her eldest brother died of tuberculosis, and another brother suffered from chronic childhood illness.

Apgar graduated in 1929 from Mount Holyoke College, where she studied zoology. Later that year she attended medical school at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, one of four females accepted in 1929. She graduated fourth in her class in 1933.

She was initially interested in a career in surgery and successfully completed a surgical internship at Columbia. The chair of surgery at Columbia discouraged her from pursuing a career in the male-dominated surgical field, however, and suggested she instead work to advance the field of anesthesiology. At the time, anesthesiology was generally handled by nurses. Apgar followed this advice and trained at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the nation's first department of anesthesia, then interned at Bellevue Hospital in New York.

At 29, Apgar was invited to found and head the Division of Anesthesia at Columbia University. As a female in anesthesiology, at the time both a male-dominated and less respected field of medicine, she served as the sole practicing anesthetist until the mid 1940s. During this era, anesthesia research developed into an accepted academic field and Apgar became the first female full professor at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Her research focused on obstetrical anesthesia and the effects on newborns of anesthetics given to expectant mothers during labor. It was here that Apgar developed and introduced the Apgar Score in 1952. Her research continued to relate the score more closely to the effects of labor, delivery, and maternal anesthetics on the baby's condition.

During sabbatical in 1959, Apgar earned a master's degree from Johns Hopkins. Her research expanded from anesthesia to genetics and the prevention of birth defects. She raised national awareness of birth defects as a national health problem through public education and fundraising for research efforts as director of the congenital defects division at the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now the March of Dimes Foundation.

After decades of honors and awards, she coauthored the 1973 book Is My Baby All Right? Apgar died in 1974.

Throughout her career as both a researcher and maternal and child health advocate, Apgar remained devoted to her patients. She proclaimed, "Nobody, but nobody, is going to stop breathing on me!" In 1994, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring Apgar as part of its Great Americans series. Former Surgeon General Julius Richmond said, "[She has] done more to improve the health of mothers, babies, and unborn infants than anyone in the twentieth century."

This profile comes from the Women of Hopkins exhibit, which honors 23 female trailblazers who have made a mark on society during or after their time at Johns Hopkins. The exhibit, launched in 2016, is on display at the Mattin Center on JHU's Homewood campus and also available online. To learn more about the selection process, and to nominate candidates for inclusion, visit women.jhu.edu/candidates.

Posted in Health

Tagged women's history month