Andre was into drugs for 20 years, dealing them, using them, ending up in jail at times or homeless because of them. He tried again and again to quit. Five years ago, it finally stuck.

"A pure miracle," he called it.

Now the 50-year-old from West Baltimore works with the advocacy group Bmore POWER as a peer educator and naloxone trainer. With so many messages about drug use coming from so many places, he said it's impossible to know which one will stick, which one will help someone make safer choices that could save his or her life.

"I had information. I had support. I had opportunities to switch lanes," he recalled. "This thing has a grip so tight."

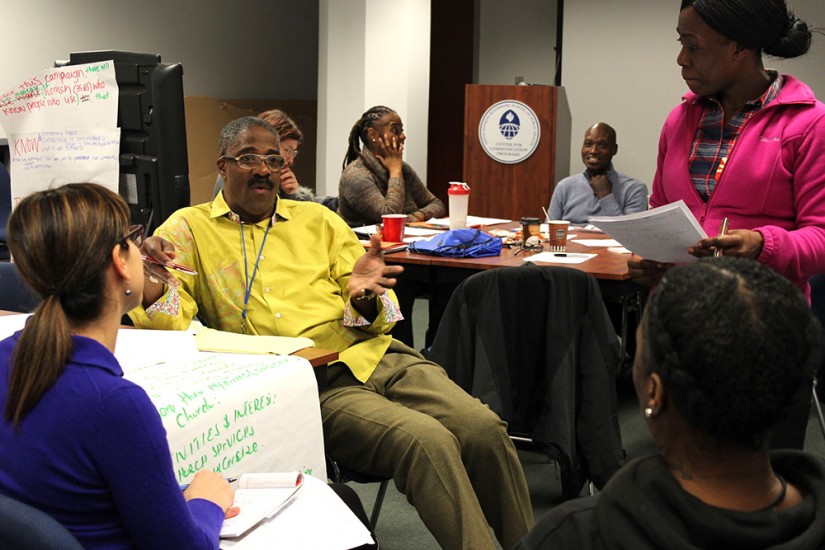

To help create messaging around substance abuse and addiction that could cut through the chatter, Andre attended a three-day hackathon at the beginning of the month organized by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs for Bmore POWER members. During the weekday retreat, they came up with slogans and messages that could help keep people from overdosing on fentanyl.

In Andre's opinion, messages should focus on how addiction is a disease and work to take away the stigma of using drugs.

"Hopefully this message will get to who it needs to get to and help save somebody's life, help somebody change their perspective about what they're doing," he said.

The statistics surrounding fentanyl use are staggering. In 2015, there were 1,259 overdose deaths in Maryland. The number was 2,089 in 2016. And when the 2017 numbers come out, they're expected to be even higher. The synthetic opioid is 30 to 50 times more powerful than pure heroin; four salt-sized grains of fentanyl can be deadly. It's also cheaper and relatively easy to get and has infiltrated the Baltimore drug supply.

"We're here to help make sure people are safe and are reducing their risk of overdose," said Cathy Church-Balin, CCP's director of business development, at the start of the hackathon. "We all communicate, but we all know some messages are better than others. We want to create messages that will motivate people in our community to change their behavior. And together we will turn your knowledge into messages we hope will be effective."

Church-Balin described CCP's P Process, which outlines the center's approach to creating strategic and evidence-based behavior change messages. The messages developed over the three days will be the starting point as Bmore POWER and CCP develop a peer-to-peer campaign warning city residents about the enormous risk posed by fentanyl and helping them understand how they can reduce those risks. Once the final messages are completed, they will be tested and fine-tuned.

Image credit: Center for Communication Programs

As the hackathon began, participants—many of whom are current and former drug users—discussed the depth of the problem. Many shared what they see every day on the streets, where they work to train people how to use naloxone, a medication that can reverse the effects of overdose. The Bmore POWER members distribute naloxone to people who use drugs or whose friends and relatives are users with the goal of saving lives.

Soon, the participants broke into small groups to create their own campaigns, using human-centered design techniques to tackle the problem. They delved into the barriers that keep messages from getting through to the people who need to hear them and discussed just who they were trying to reach. They created videos and songs and slogans. They talked about putting messages on flyers, inside metro cars, on Instagram, on the outside of bags containing clean syringes.

"I've been using for years. I thought I was a pro. Then I OD'd," was one of the new messages, aimed at younger drug users who may perceive themselves as invincible.

Nathan Fields, a community health educator, also tried a variation containing the kind of language not often heard in public service announcements.

"We've been speaking bureaucratic language for so long and it has done nothing," he said. "If using that language will get them better, then we should do it."

Another potential campaign focused on messages of self-empowerment: "Fentanyl Kills. My family, my friends, my community, my city. We have the power to stop it."

Many of the ideas also focused on making sure people understand how they can reduce harm: by not using drugs alone (so someone can get help if there is an overdose), by carrying naloxone, by having a plan in case something goes wrong, and more.

After all of the ideas were presented, many participants praised the outcome and the process, despite initial skepticism. One said that while many opioid campaigns are "condescending," what she saw at the hackathon was anything but.

Douglas Fuller, a peer educator with Bmore POWER and harm reduction advocate, said the job of the hackathon was similar to the work of convincing people to wear seat belts in the car or wear helmets when riding a bike.

"Because of fentanyl, people might have to adapt how they are using drugs," he said. "A lot of people are going to keep using, so we have to help them do it safer."

Posted in Health

Tagged opioids, drug abuse, center for communication programs