If you're looking into recent crime activity in your neighborhood, chances are you can check out a Google map dotted with incident locations. Click further, and you can find the type of crime reported, the date and time it occurred, and other details.

Behind the scenes, different police departments use widely different methods for documenting crime stats. But to translate that work to a user-friendly Google map, various cities are lining up their data under a single, uniform format.

There lies the concept of "data standards," a movement that's bringing new structure to the Wild West of open data-sharing for local governments.

Image caption: For apps like SpotCrime (above) to provide information about local crimes, they need municipalities to report data in a uniform way.

Image credit: SpotCrime

"What we're starting to see is an emergence of different cities publishing similar types of data in the public domain," says Andrew Nicklin, the data practices director for Johns Hopkins University's Center for Government Excellence, or GovEx.

To maximize public reach, he says, it often makes sense for the cities to be following the same rules for formatting and presenting that data.

With crime, for example, a guideline many cities follow is "SOCS," short for SpotCrime Open Crime Standard—which is used with the Google crime maps. It requires logging a number of details for each crime—time, geographic coordinates, case number, and so forth—in specified formats, like using military time.

Dozens of other standards have also gained currency in recent years for other types of government data, from transit schedules and budgets to 311 calls and legislation.

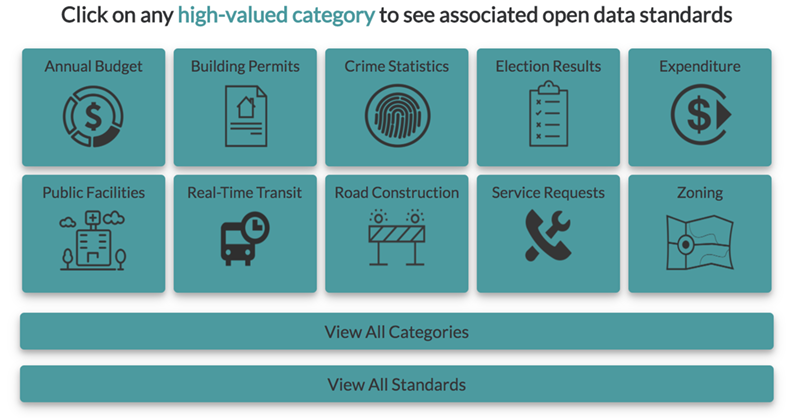

Now, for the first time, there's a single online hub that gathers all of these different guidelines together in one place: The Data Standards Directory.

The new tool, which GovEx developed in partnership with McGill University's Geothink, provides easy access to over 60 widely used data standard guidelines across 11 different categories of government functions.

Image caption: The Data Standards Directory offers guidance on reporting crime statistics, election results, service requests, real-time transit, and many more civic data sets

Image credit: Data Standards Directory

Before its existence, city officials working with data had to wade through spreadsheets to look into different standards, according to Michael Schnuerle, the city data officer for Louisville, Kentucky.

"There was no central location to see what's out there for different types of data, or to inform your decision on whether to align to a certain standard," Schnuerle says.

He says a major benefit to aligning is for city officials to expand data work "beyond your own bubble … so you can cross-compare with other cities in a more accurate way."

Also see

Nicklin also points to the benefits in making government data more accessible for tech platforms and research.

"For the people who consume the data—Google, or university researchers, people in startups wanting to make mobile apps—the more thee things are standardized, the easier it is to scale their work across multiple governments," he says.

The directory is already an international effort with its Canadian origins—spawning from a thesis project of McGill researcher Rachel Bloom, with Geothink's Renee Sieber—and its inclusion of a handful of Spanish-language standards.

With its crowdsourcing element, the resource will add depth as more data experts across the world contribute, Nicklin says.

"There's a lot more standards we want to dig up and incorporate," he says. "We aim for this to be community-oriented and community-supported."

The website was funded through Bloomberg Philanthrophies' What Works Cities program, an initiative that promotes increased use of data in local government.

Posted in Science+Technology, Politics+Society

Tagged data, center for government excellence, cities