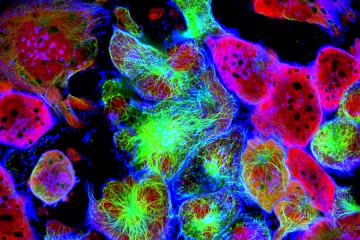

In a bid to detect cancers early and in a noninvasive way, scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center report they have developed a test that spots tiny amounts of cancer-specific DNA in blood and have used it to accurately identify more than half of 138 people with relatively early stage colorectal, breast, lung, and ovarian cancers.

The test, the scientists say, is novel in that it can distinguish between DNA shed from tumors and other altered DNA that can be mistaken for cancer biomarkers.

A report on the research, performed on blood and tumor tissue samples from 200 people with all stages of cancer in the United States, Denmark, and the Netherlands, appears today in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"This study shows that identifying cancer early using DNA changes in the blood is feasible and that our high accuracy sequencing method is a promising approach to achieve this goal," says Victor Velculescu, professor of oncology at the Kimmel Cancer Center.

Blood tests for cancer are a growing part of clinical oncology, but they remain in the early stages of development. To find small bits of cancer-derived DNA in the blood of cancer patients, scientists have frequently relied on DNA alterations found in patients' biopsied tumor samples as guideposts for the genetic mistakes they should be looking for among the masses of DNA circulating in those patients' blood samples. To develop a cancer screening test that could be used to screen seemingly healthy people, scientists had to find novel ways to spot DNA alterations that could be lurking in a person's blood but had not been previously identified.

"The challenge was to develop a blood test that could predict the probable presence of cancer without knowing the genetic mutations present in a person's tumor," says Velculescu.

The goal, adds Jillian Phallen, a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center who was involved in the research, was to develop a screening test that is highly specific for cancer and accurate enough to detect the cancer when present, while reducing the risk of "false positive" results that often lead to unnecessary over-testing and over-treatment.

To develop the new test, Velculescu, Phallen and their colleagues obtained blood samples from 200 patients with breast, lung, ovarian, and colorectal cancer. The scientists' blood test screened the patients' blood samples for mutations within 58 genes widely linked to various cancers.

Among 42 people with colorectal cancer, the test correctly predicted cancer in 50 percent of patients with stage I, 89 percent of patients with stage II, 90 percent of patients with stage III, and 93 percent of patients with stage IV disease. For patients with lung cancer, the test correctly identified cancer among 45 percent of patients with stage I disease, 72 percent with stage II disease, 75 percent with stage III, and 83 percent with stage IV cancer. For 42 patients with ovarian cancer, the test identified 67 percent with stage I, 75 percent with stage II, 75 percent with stage III, and 83 percent with stage IV disease. Among 45 breast cancer patients, the test spotted cancer-derived mutations in 67 percent of patients with stage I disease, 59 percent with stage II, and 46 percent with stage III cancers.

Overall, the scientists were able to detect 86 of 138—62 percent—stage I and II cancers, and found none of the cancer-derived mutations among blood samples of 44 healthy individuals.

Despite these initial promising results for early detection, the blood test needs to be validated in studies of much larger numbers of people, say the scientists.

Velculescu and his team also performed independent genomic sequencing on available tumors removed from 100 of the 200 patients with cancer and found that 82 percent had mutations in their tumors that correlated with the genetic alterations found in the blood.

He says the populations that could benefit most from such a DNA-based blood test include those at high risk for cancer, including smokers, for whom standard computed tomography scans for identifying lung cancer often lead to false positives, and women with hereditary mutations for breast and ovarian cancer within BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health