The nine student curators have a few decisions to make in class today.

The Long Sixties, a spring 2017 semester offering in Johns Hopkins University's Department of the History of Art, has students choosing, researching, and writing about images made by Danish artist Asger Jorn—from posters he produced for the May 1968 protests in Paris to the creative imagery he made for the journal of the avant-garde group CoBrA, a loose alliance of artists from Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam that existed from 1948-51. The student's work will be seen in the exhibit "Asger Jorn and CoBrA," which opens April 26 at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library.

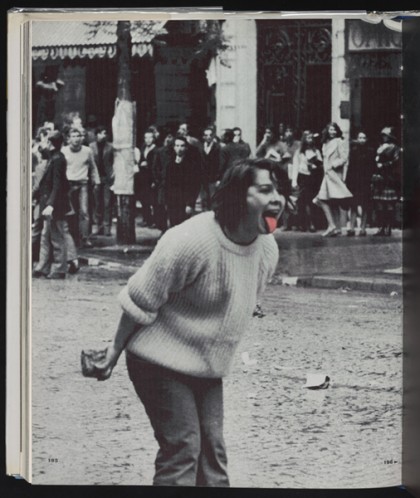

Image caption: Illustration by Asger Jorn, from the book “La langue verte et la cuite: e?tude gastrophonique sur la marmythologie musiculinaire,” Paris, J.-J. Pauvert, 1968

But first, during this early April class, they need to finalize their wall text for the images they selected. They need to discuss edits and rewrites that need to be made to the banner text that provides an overview for the entire exhibition. And they need to decide what Jorn image might best accompany that introductory banner. Molly Warnock, an assistant professor of art history who designed this class, shows the students a Jorn print that features three figures, roughly sketched and rendered in black and yellow, against a pink background. It's an image the students picked during their research but didn't end up using in the exhibit. Warnock wanted to know how they felt about using it for the banner. And since they also need to think about programming activities and refreshments for the opening, Warnock adds, "It would also look good on a cake." The students laugh quickly and then immediately start discussing how and why it might work, what layout might work well with the text, and what they need to do to the banner text to make it fit with the image. The entire exhibition preparation is a hands-on, collaborative approach to turning their research into visual presentation—translating the expertise that might go into a term paper into a project that speaks to a general audience. The Long Sixties is the third time Warnock has invited students to interact with the MSE's extensive collection of 20th-century art journals, which includes everything from Surrealist and Dada publications to Lettrism. Creating an exhibition using the journals gives undergraduates a rare chance to do research through primary sources, about which there might not always be a great deal of collateral information already published.

A class like The Long Sixties "draws attention to one of our great, underused resources," Warnock says of the art journal collection. For the first few weeks of class, the students researched an object, such as a specific piece from the CoBrA journal, and told their peers about it during class.

"They all present their objects and make specific recommendations about whether to show it in the exhibition," Warnock says. "And if we show it, how do we show it, what features particularly help us elucidate some themes that we've been talking about? It really gets them thinking about how you make arguments with visual material." That process is a different form of communication than making an argument in writing.

"It's asking students to think in a different way," Warnock says. "So they have to get really creative as researchers, which is good, I think, and increasingly important as more and more stuff is available on the internet. They have to learn to trust themselves as interpreters in a different way." Trusting themselves to tell a different story is echoed in the way Warnock structured the entire class. The Long Sixties begins by talking about the student uprisings and social upheavals that spread through Western European art and culture in 1968 and then looks back to the immediate postwar period and wonders how it got there. One way to get a handle on that history is to look at the various shifts in visual art and art practice going on during this time period, an era when American art, such as Abstract Expressionism, often monopolizes postwar art history surveys. "We talk about the ways in which the dominance of America after the war and American capital, in particular, led to a particular canon formation in the postwar period," Warnock says. "So we're looking at a broad swath of aesthetic and critical production across Western Europe—primarily Germany, Italy, and France—and trying to understand the new kinds of publics that this art imagines for itself or is actively trying to create. We talk about the new claims toward participatory aesthetics that we see being elaborated, the idea that the work of art has a direct role to play in the transformation of contemporary society."

Also see

The Danish artist Jorn, who the students researched for the exhibition, is a representative artist to explore this topsy-turvy era of European art.

"One of the things that has made European art so incredibly hard for us to map, particularly as compared with the seemingly neat succession of major movements in the U.S., is that European art is a gallimaufry of incredibly volatile avant-garde groups that come into being and just as quickly disappear," Warnock says. "In the 1940s and '50s, you have these ephemeral groups who come together for an issue of a journal or an exhibition. And Jorn never met one of those groups that he didn't like." In addition to his native Danish, Jorn spoke English, French, Italian, German—"none of them particularly well but certainly unabashedly," Warnock says—and he was an enthusiastic collaborator.

"He understands [collectivity] as being the only real possibility for a revolutionary practice, that a new way of making art should also be a new way of being with others," Warnock says. "He's like this free agent looking to collaborate with anybody, so he's this classically peripatetic, postwar artist through whom you can trace broader concerns." This exploration of new ways of thinking about art and its relationship to social movements is timely, for many American artists today are wrestling with similar issues and concerns. That echo was more coincidence than by design.

"The goal is not simply to have a better understanding of this one specific period, though that's part of it," Warnock says. "I'd like for this to be a class whose significance is not strictly historical, in ways that are maybe not entirely apparent right now. I had those classes in college where, sometimes, it took a couple of years out to think, 'Oh, this is why we spent so much time talking about that text, there are ways it still feels relevant to what is going on right now.' It's meant to provide them with permanently useful things." "Asger Jorn and CoBrA" opens April 26 on M Level of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library with a reception from 4-7 p.m.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged art, art history