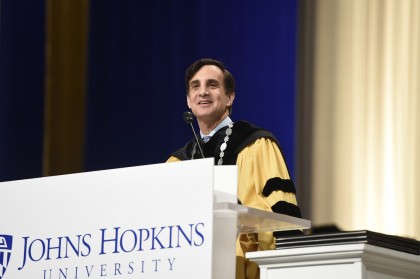

Remarks as prepared for Johns Hopkins University President Ronald J. Daniels for the universitywide commencement ceremony on May 18, 2016.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

To our honorary degree recipients, alumni, and trustees, to our faculty and staff, to our parents, family members and friends, and most especially to our graduates, welcome to the Johns Hopkins University commencement for the great Class of 2016!

Now I know some of you may not have aspired to be the first to graduate in the Royal Farms Arena—a temple to our local convenience store, to fried chicken tenders and western fries. But trust me: Your dry, comfortable, warm families and friends think that you are the most thoughtful and brilliant class ever, given the cold and rainy deluge that has descended upon Baltimore over the last three weeks.

Indeed, during your time here, you have brought that same characteristic thoughtfulness and brilliance to so many large and vexing questions: Is it acceptable to eat your weight in shrimp at Sunday brunch at the FFC? Which will you sneak into: Gilman Tower or the steam tunnels? Or both? Is it okay to steal a "saved seat" in the Brody Reading room?

Of course, we know these are not the truly significant concerns upon which you've focused during your years at Johns Hopkins. Instead your focus, and your studies, have opened new understandings of creative expression, scientific discovery, and social and economic theory.

And you have been here at a time when the national and local conversation has been framed by urgent and probing issues of race, class, politics, and justice. All issues that at their core are about the complex nature of human experience and perspective—and the institutions that shape, embody, and perpetuate that complexity.

Sometimes we confront this complexity in people and in institutions at some distance, but more often we do so in close and very personal ways. Let me share one example with you.

Each morning I leave my house on campus and walk along Bowman Drive to my office at Garland Hall. It is named for Isaiah Bowman, the fifth president of Johns Hopkins University, who served from 1935 to 1948. His term spanned the rise of Nazism in Europe and the cataclysm of World War II and its immediate aftermath.

As some of you well know, Dr. Bowman's story is complicated.

Here's the good: He was a renowned geographer and academic leader, whose vision for the university included bringing the Applied Physics Laboratory into our institution and sowing the seeds of interdisciplinary research that have proven so prescient today. As a public servant, he advised presidents and participated in the discussions that launched the United Nations.

But here's the rest of the story: Dr. Bowman was an unrepentant racist and an anti-Semite. He introduced a 10% quota for Jewish students at a time when many other institutions of higher education in the United States were ending such practices. He actively blocked the hiring of Jews into the professoriate and derailed the applications of African-American students against the recommendations of the faculty.

I am a Jew, whose father emigrated from Europe on the eve of the Holocaust. As you would expect, I have a visceral reaction to Dr. Bowman. He is a flawed leader whose ideas and actions are not only reprehensible to me from the perspective of the present, but even I believe inexcusable in the context of his own time.

And yet, his accomplishments—individually and on behalf of our university—are also real and undeniable.

On that daily walk, I am unavoidably in dialogue with a man whose views I abhor, but whose legacy lives on at the university—the recipient of his successes and his failures.

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote: "The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function."

I take from this not that we should adopt a naïve view of the world that suggests you can find good in anyone no matter how harmful their views or actions may be. Nor that we should be governed by a convenient moral relativism and therefore incapable of judgment.

Rather, we must be open to the complexities and contradictions of humankind. And through that broad aperture seek better, more informed, and more just decisions for ourselves, for our institutions and for our society.

We know we are living in a moment of oversimplification. This is a world where we judge potential partners with a swipe. Where policy debates are adjudicated in 140 character tweets. Where the news cycle is 24 hours, yet reduces opinions—on everything from pandemics to geopolitical upheaval to Beyoncé's marriage—to a 30-second sound bite.

In this context, we must strain to see, to understand, and to reckon with greater complexity. If we do not, we deny ourselves the opportunity to learn from people's flaws or to be astonished by their abilities. If we do not, we are robbed of the chance to let multiple strains of information collide and percolate in our minds as we form more nuanced interpretations—ones that can help us navigate a way forward in a world that is rarely sketched in black and white, but instead painted in rich hues of gray.

Your commencement speaker, Spike Lee, illuminates the nuances of the human character in his masterpiece film, Do The Right Thing, a film that I still find bracing nearly 30 years after I first saw it.

The film explores the intertwined experiences of neighbors in a Brooklyn community on the verge of explosive racial conflict. In the midst of this slice-of-life drama, Spike Lee inserted a series of straight-to-camera tirades by characters representing all the races and ethnicities in the neighborhood. Each was more invective-filled and racially charged than the next. It is searing.

The viewer is forced to confront the contradictions of these characters. Some hold deeply bigoted views. And yet, they also live cheek-by-jowl with one another, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in conflict. No character is one-note. Only when taken together can we understand fully the picture of life in that community, at that moment.

And whether on screen or in our own lives, it is only by holding such contradictions and complexities that we can understand and hope to change the trajectory of our shared story.

Graduates of the Class of 2016, you are an extraordinarily talented, fearless, and determined group of people. You have spent time here honing your many extraordinary gifts. We are counting on you to be among those who are able to see—who are determined to see—the full scope, the full complexity of the human experience. The world will be the better for that.

We are so very proud of you.

Godspeed and congratulations to the great Class of 2016.

Posted in University News

Tagged commencement 2016