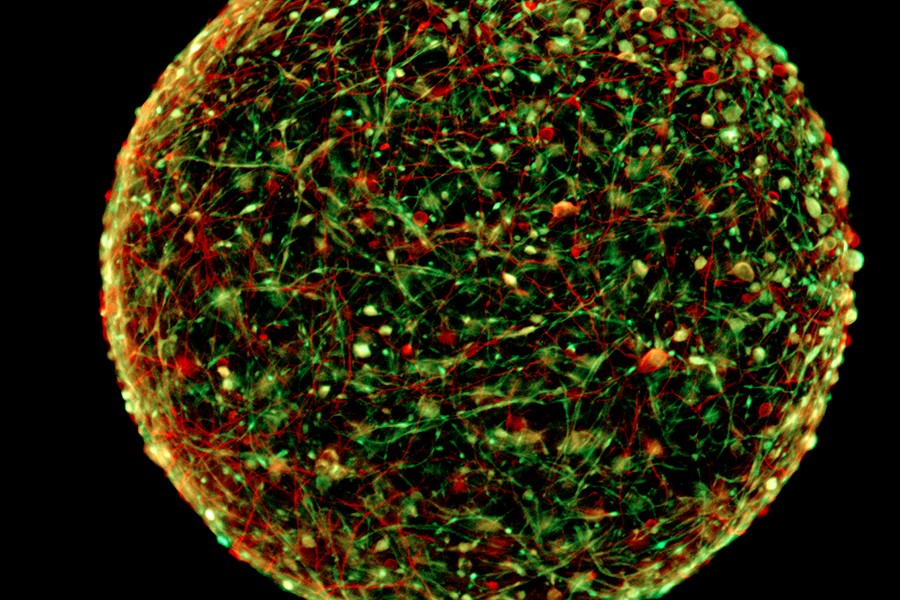

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have grown tiny, barely visible "mini-brains," balls of human neurons and other cells that mimic some of the brain's structures and functionality. The development of the mini-brains could dramatically change brain research and drug testing, replacing hundreds of thousands of animals used now in neurology labs.

Performing research using these three-dimensional mini-brains—which grow and form brain-like structures on their own over the course of eight weeks—should be superior to studying mice and rats because they are derived from human cells instead of rodents, researchers say. The findings will be presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference in Washington, D.C., this weekend.

"Ninety-five percent of drugs that look promising when tested in animal models fail once they are tested in humans at great expense of time and money," says study leader Thomas Hartung, professor of environmental health sciences at the Bloomberg School. "While rodent models have been useful, we are not 150-pound rats. And even though we are not balls of cells either, you can often get much better information from these balls of cells than from rodents.

"We believe that the future of brain research will include less reliance on animals, more reliance on human cell-based models."

Also see

Hartung and his colleagues created the mini-brains using what are known as induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs—adult cells genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic stem cell-like state and then stimulated to grow into brain cells. Cells from the skin of several healthy adults were used to create the mini-brains, but Hartung says that cells from people with certain genetic traits or certain diseases can be used to create mini-brains to study various types of pharmaceuticals. He says the mini-brains can be used to study Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and even autism. Projects to study viral infections, trauma, and stroke have been started.

Hartung's mini-brains are very small—at 350 micrometers in diameter, they are about the size of the eye of a housefly and are just visible to the human eye—and hundreds to thousands of exact copies can be produced in each batch. One hundred of them can grow easily in the same petri dish in the lab. After about two months, the mini-brains developed four types of neurons and two types of support cells. They even showed spontaneous electrophysiological activity, which could be recorded with electrodes, similar to an electroencephalogram, or EEG. To test them, researchers placed a mini-brain on an array of electrodes and listened to the spontaneous electrical communication of the neurons as test drugs were added.

Hartung is applying for a patent and is also developing a commercial entity to produce mini-brains, perhaps starting this year. He says they are easily reproducible and hopes to see them in as many labs as possible.

"We don't have the first brain model, nor are we claiming to have the best one," says Hartung, who also directs the School's Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing. "But this is the most standardized one. And when testing drugs, it is imperative that the cells being studied are as similar as possible to ensure the most comparable and accurate results."

Read more from School of Public HealthPosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged brain science, neuroscience, neurology, biomedical research