Apparently there's safety in numbers, even for cancer cells. New research from Johns Hopkins suggests that cancer cells rarely form metastatic tumors on their own, preferring to travel in groups to increase their collective chance of survival.

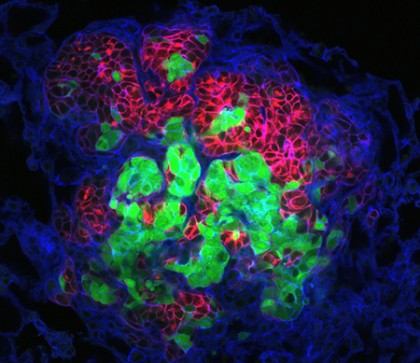

Image caption: A metastasis now growing in lung tissue (blue) that originated from at least two cells (red and green) from a multicolored tumor in the mammary gland of a mouse.

Image credit: Courtesy of Breanna Moore, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

In a report on the study published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers say they also found that traveling cells differ from those multiplying within a primary tumor, and that the difference may make them naturally resistant to chemotherapy.

"We found that cancer cells do two things to increase their chances of forming a new metastasis," says Andrew Ewald, professor of cell biology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "They turn on a molecular program that helps them travel through a diverse set of environments within the body, and they travel in groups."

Metastasis, the complex way that tumor cells spread through the body, causes more than 90 percent of cancer-related deaths. Most chemotherapy drugs target proliferating cells and won't kill metastasizing cells, which leaves patients vulnerable to new tumors.

Ewald and his team tested mice with a form of mammary gland cancer known to spread to the lungs. They found that fewer than three percent of the metastases came from a single cell, and discovered cell clusters at each step of the destination to the lungs—in tissue, blood vessels, and blood.

Next, the researchers tested whether group travel gave the cells an advantage. In lab tests they found that clusters were at least 15 times better at forming colonies than single tumor cells. When they repeated the test in mice, the clusters were more than 100 times better at creating large metastases.

"You can think of metastasis as The Amazing Race," says Ewald. "The cells encounter many different challenges as they attempt to grow and spread, and some cells are better at different events than others, so traveling in a group makes sense."

The team also looked at whether traveling cells showed any particular molecular hallmarks that could be used to predict and ultimately prevent tumor spread. Building on previous research, they reaffirmed the role of the protein K14, which showed up in high levels in small, traveling cell clusters.

K14 levels also helped identify different types of gene activity, revealing whether the cells were on a program for proliferation or metastasis. These findings, Ewald says, could eventually be used to develop new drugs to target metastasizing cells specifically.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged cancer, cell biology