The Johns Hopkins University's School of Medicine's Brain, Learning, Animation, Movement lab has released an interactive video game, "Bandit's Shark Showdown," that could help rehabilitate stroke victims. An article published in the Nov. 23 issue of The New Yorker explores the inspiration and development process behind an app that combines cutting-edge robotics, neuroscience, and game design.

Many stroke victims suffer hemiparesis, weakness on one side of their body. But, The New Yorker's Karen Russell writes, "the tissue death that results from stroke appears to trigger a self-repair program in the brain. For between one and three months, the brain enters a growth phase of molecular, physiological, and structural change that in some ways resembles the brain environment of infancy and early childhood. The brain becomes, as one researcher told me, 'exquisitely sensitive to our behavior.'"

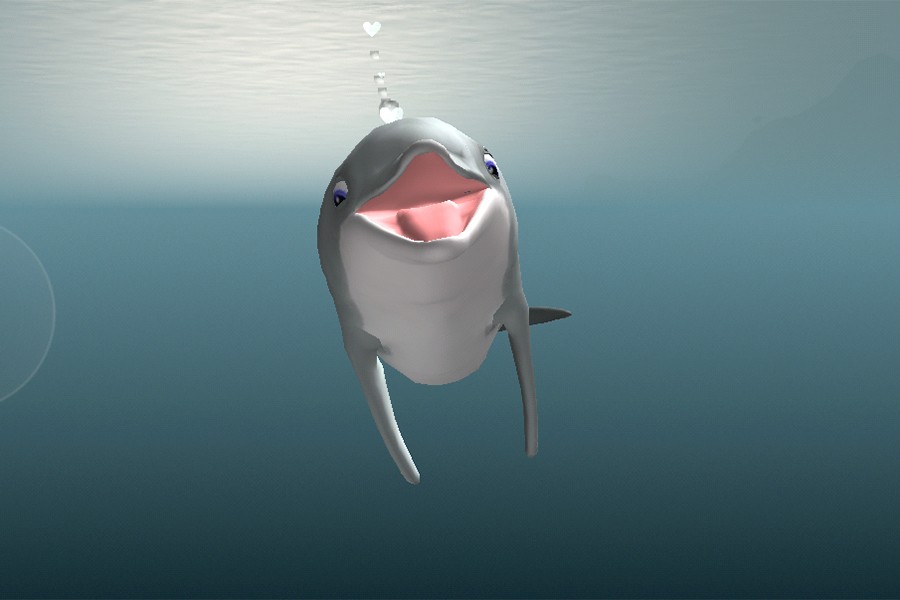

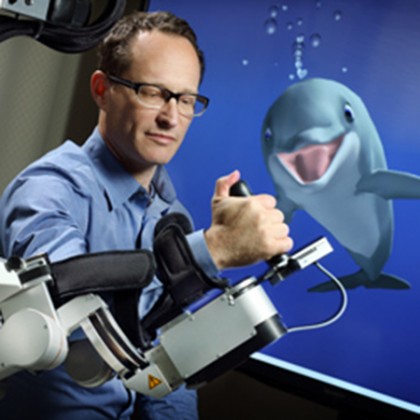

The lab, led by John Krakauer, professor of neurology and neuroscience at JHU's School of Medicine, aims to capitalize on that post-stroke development stage. His team studied the locomotion of dolphins and developed an app that relies on "non-task-based tasks" that engage users and motivate them to play and relearn motor skills. With the use of a robotic arm outfitted with a motion-capture camera, the game challenges users to control the movement of a dolphin in the water with their arms. The user and Bandit the dolphin are one, hunting mackerel and battling sharks.

"There's no right and wrong when you're playing as a dolphin," Krakauer told The New Yorker. "You're learning the ABCs again—the building blocks of action. You're not thinking about your arm's limitations. You're learning to control a dolphin. In the process, you're going to experiment with many movements you'd never try in conventional therapy."

More, from The New Yorker report:

Read more from The New YorkerIn December 2010, Krakauer arrived at Johns Hopkins. His space, a few doors from the Moore Clinic, an early leader in the treatment of AIDS, had been set up in the traditional way—a wet lab, with sinks and ventilation hoods. The research done in neurology departments is, typically, benchwork: "test tubes, cells, and mice," as one scientist described it. But Krakauer, who studies the brain mechanisms that control our arm movements, uses human subjects. "You can learn a lot about the brain without imaging it, lesioning it, or recording it," Krakauer told me. His simple, non-invasive experiments are designed to produce new insights into how the brain learns to control the body. "We think of behavior as being the fundamental unit of study, not the brain's circuitry. You need to study the former very carefully so that you can even begin to interpret the latter."

Krakauer wanted to expand the scope of the lab, arguing that the study of the brain should be done in collaboration with people rarely found on a medical campus: "Pixar-grade" designers, engineers, computer programmers, and artists. Shortly after Krakauer arrived, he founded the Brain, Learning, Animation, Movement lab, or BLAM! That provocative acronym is true to the spirit of the lab, whose goal is to break down boundaries between the "ordinarily siloed worlds of art, science, and industry," Krakauer told me.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged robotics, neuroscience