On Wednesday, President Barack Obama announced a historic shift in U.S. relations with Cuba, a move to normalize diplomatic relations between the two neighboring countries after more than five decades of hostility.

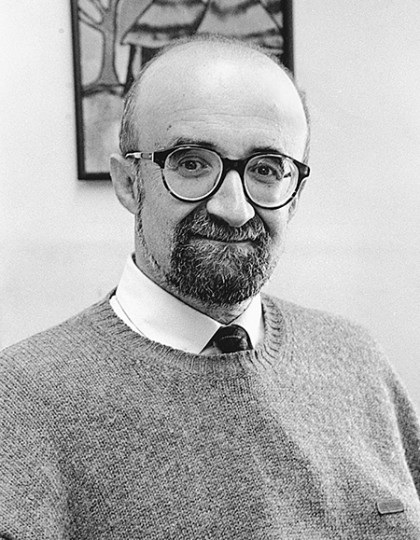

Image caption: Piero Gleijeses

For perspective on this announcement, we reached out to Piero Gleijeses, a professor of American foreign policy at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C., and a renowned scholar of Cuban foreign policy under Fidel Castro, the revolutionary turned politician who ruled Cuba from 1959 until 2008. Gleijeses is the author of several essays and two books on the topic—Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa,1959-1976 (Chapel Hill, 2002), which won the Robert H. Ferrell Book Prize from the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations in 2003; and Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991 (Chapel Hill, 2013), which won the Friedrich Katz Prize from the American Historical Association earlier this year.

Gleijeses first traveled to Cuba in 1980 as part of an academic exchange between SAIS and the University of Havana. In 1994, he began conducting research in the closed Cuban archives—the only foreigner who has been allowed to do so in the past 55 years—and over the next two decades visited Cuba about three times a year, on average, with each visit lasting three to five weeks, he said.

In an email interview, Gleijeses shared his insights on the origins of the tension between the U.S. and Cuba, what has been accomplished by the economic embargo imposed by the U.S., and what the thawing of relations could mean in the near-term.

What is at the root of the long-standing animosity between the U.S. and Cuba?

The animosity precedes Fidel Castro. It has a long history. President Thomas Jefferson longed to annex the island, and his successors agreed that Cuba would one day belong to the United States. No one understood this better than José Martí, the father of Cuban independence. In 1895, as Cuba's revolt against Spanish rule began, he wrote, "What I have done, and shall continue to do, is to ... block with our [Cuban] blood ... the annexation of the peoples of America to the turbulent and brutal North that despises them. ... I lived in the monster [the United States] and know its entrails—and my sling is that of David." [1]

In 1898, the United States joined the war against an exhausted Spain, ostensibly to free Cuba. After Spain surrendered, Washington forced the Platt Amendment on the Cubans, which granted the United States the right to send troops to the island whenever it deemed it necessary and to establish bases on Cuban soil. (Today, the Platt Amendment lives on in the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay.) Cuba became, more than any other Latin American country, "an American fiefdom." [2]

Until 1959, when Fidel Castro came to power.

When Americans look back at that fateful year, they are struck by their good intentions and by Castro's malevolence. President Dwight Eisenhower sought a modus vivendi with Castro—as long as Cuba remained within the U.S. sphere of influence and respected the privileges of the American companies that dominated the island's economy. Castro, however, was not willing to bow to the United States. "He is clearly a strong personality and a born leader of great personal courage and conviction," U.S. officials noted in April 1959, and, a few months later, a National Intelligence Estimate reported, "He is inspired by a messianic sense of mission to aid his people." [3] Even though he did not have a clear blueprint of the Cuba he wanted to create, Castro dreamed of a sweeping revolution that would uproot his country's oppressive socioeconomic structure. He dreamed of a Cuba free of the United States. Eisenhower was baffled, for he believed, as most Americans still do, that the United States had been the Cubans' truest friend, fighting Spain in 1898 to give them independence. "Here is a country," he marveled, "that you would believe, on the basis of our history, would be one of our real friends." As U.S. historian Nancy Mitchell has pointed out, "our selective recall not only serves a purpose, it also has repercussions. It creates a chasm between us and the Cubans: we share a past, but we have no shared memories." [4]

Over the next three decades—until the end of the Cold War—Fidel Castro became the Americans' obsession. By the 1970s, the problem was not Cuban domestic politics; it was Castro's policy in the Third World—above all in Africa. In 1975 Henry Kissinger had been ready to normalize relations with Cuba, until Fidel Castro sent 36,000 soldiers to Angola. They went to repel a South African invasion that had been abetted by the United States and to fight for what Castro has called "the most beautiful cause," [5] the struggle against apartheid. The Ford administration was outraged by the Cuban soldiers in Angola and claimed that they were "proxies" of the Soviet Union.

Some people in the Carter administration knew better. Robert Pastor, a bright specialist on Latin America in the National Security Council, noted: "I view the Soviet-Cuban relationship as somewhat analogous to the U.S.-Israeli relationship. Most of the world believes that we have overpowering influence over Israel ... but in reality, they are pulling us around a lot more than we are pushing them. Similarly, my guess is that the Cubans are pushing and pulling the Soviets into riskier areas than the elder Soviet leadership would normally choose to tread. The Cubans are nobody's puppet." [6]

U.S. policy did not change: the Carter and Reagan administrations refused to consider normalizing relations with Havana until the Cuban troops left Angola. Castro, however, would not bend. The Cubans stayed in Angola to defend it from apartheid South Africa. They stayed to train the Namibian guerrillas who were fighting to free their country from Pretoria's rule. They stayed to help the guerrillas of Nelson Mandela's African National Congress. By 1991, the Cuban troops had humiliated Pretoria's army, which changed the course of southern African history.

While this earned Washington's wrath, it won the gratitude of Africans. In July 1991, Nelson Mandela visited Havana. "We come here with a sense of the great debt that is owed the people of Cuba," he said. "What other country can point to a record of greater selflessness than Cuba has displayed in its relations to Africa?" [7]

What has the U.S. gained from its near 55-year embargo of Cuba?

As President Obama bluntly acknowledged, the embargo failed. The Castro brothers are still in power, and they did not succumb at any point to Washington's threats and blandishments. This compounded the frustration in Washington.

The most important example of the failure of U.S. efforts is in Africa. Although Jimmy Carter claimed, early in his presidency, that he wanted to normalize relations with Havana, he added a proviso: Castro had first to withdraw his troops from Angola. But Castro did not budge. "We are deeply irritated, offended and indignant that for nearly 20 years the blockade [the embargo] has been used as an element of pressure in making demands on us," he told U.S. officials in December 1978. "Perhaps I should add something more. There should be no mistake—we cannot be pressured, impressed, bribed or bought ... Perhaps because the U.S. is a great power, it feels it can do what it wants and what is good for it. It seems to be saying that there are two laws, two sets of rules and two kinds of logic, one for the U.S. and one for other countries. Perhaps it is idealistic of me, but I never accepted the universal prerogatives of the U.S.—I never accepted and never will accept the existence of a different law and different rules. ... I hope history will bear witness to the shame of the United States which for twenty years has not allowed sales of medicine needed to save lives. ... History will bear witness to your shame." [8]

Even after the Cold War ended, there was no thaw. Leycester Coltman, a former British ambassador to Cuba, wrote in 2003 that Fidel Castro was "still a bone ... stuck in American throats. He had defied and mocked the world's only superpower, and would not be forgiven." [9] U.S. officials and pundits pondered what to demand of the errant Cubans before Washington would lift the embargo, forgetting that it is the United States that tried to assassinate Castro, carried out terrorist actions against Cuba, and continues to occupy Cuban territory—Guantanamo, the filthy lucre of 1898. Their selective recall allowed them to transform Cuba into the aggressor and the United States into the victim. It was not love of democracy or concern for the welfare of the Cuban people that motivated the Americans. The vote of the Cuban Americans and the desire for revenge—nothing more—explained the continuation of the embargo.

President Obama has taken a long overdue step. It serves the material interests of the United States and it will enhance the prestige of the United States, whose Cuban policy has been repeatedly condemned at the General Assembly of the United Nations; it will ease relations with the Latin American countries, which were beginning to challenge openly the constraints that the embargo imposed on their own dealings with Cuba. But, above all, Obama's decision marks the beginning of the end of a sordid chapter in U.S. foreign policy.

1 Martí to Manuel Mercado, May 18, 1895, in Martí, Epistolario, Havana, 1993, 5: 250. ?

2 Tad Szulc, Fidel: A Critical Portrait, New York, 1987, p. 13.?

3 "Unofficial Visit of Prime Minister Castro of Cuba to Washington—A Tentative Evaluation," enclosed in Herter to Eisenhower, Apr. 23, 1959, U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States 1958-60, Washington DC, 1991, 6:483; CIA, Special National Intelligence Estimate, "The Situation in the Caribbean through 1959," June 30, 1959, p. 3, National Security Archive, Washington D.C.?

4 Eisenhower press conference, Oct. 28, 1959, in United States, General Services Administration, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1959, Washington DC, 1960, p. 271; Nancy Mitchell, "Remember the Myth," News and Observer (Raleigh, N.C.), Nov. 1, 1998, G5.?

5 Castro, in "Indicaciones concretas del Comandante en Jefe que guiarán la actuación de la delegación cubana a las conversaciones de Luanda y las negociaciones de Londres (23-4-88)," p. 5, Archive of the Cuban Armed Forces, Havana.?

6 Pastor to Brzezinski, July 19, 1979, NLC-24-13-5-7-9, Jimmy Carter Library, Atlanta.?

7 Mandela, quoted in The Washington Post, July 28, 1991, p. 32.?

8 Memcon (Tarnoff, Pastor, Castro), Dec. 3-4, 1978, 10 p.m.-3 a.m., pp. 2, 5, 9-10, 25, Vertical File: Cuba, Jimmy Carter Library, Atlanta.?

9 Coltman, The Real Fidel Castro, New Haven, 2003, p. 289.?

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged foreign policy, cuba