In May 2012 Baltimore filmmaker, artist, and author John Waters left his Baltimore home looking for a ride. He walked to the corner of a nearby busy street and held up a sign. His ultimate goal: to reach his apartment in San Francisco, about 2,800 miles away. He just needed a good start, somebody to take him from the city toward Interstate Highway 70 heading west.

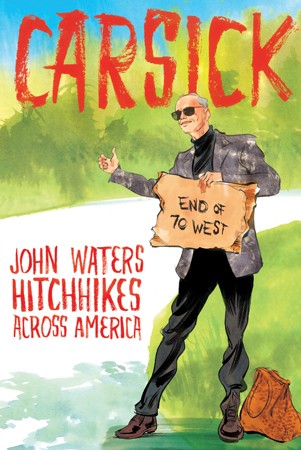

Over the next nine days Waters would be picked up by a farmer, a cop, some renegade builders heading toward the promise of work, the indie-rock band Here We Go Magic, and a young Republican in his parents' sports car whom Waters calls the Corvette Kid, who doesn't merely give Waters a ride but drives across country to catch up with him and give him a lift across three western states. That adventure is documented in Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America, a page-turning read featuring the 66-year-old Waters recalling what it's like to stand by the side of the road, in the rain, for hours at a time waiting for a kind soul willing to give him a lift. Waters reads from his book at 6 p.m. this evening at the Barnes & Noble Johns Hopkins at 6 p.m.

And as Carsick recounts, the people who picked him up were all kind souls, not the psychopaths he imagines might be out there in one of the book's two fictional sections. Waters opens Carsick with a pair of inspired fantasies in which he imagines the best that could happen on his journey and the worst, sections that read very much like his movies. These two parts are ribald, profane, and hilarious, so over-the-top that the actual hitchhiking journey may seem mundane by comparison. But that's what is so impressive about the book—the Pope of Trash visits middle American and adores each and every average person he comes across just as much as he does the misfits of his films.

The Hub caught up with Waters by phone to talk about hitchhiking and his long-standing relationship with Johns Hopkins University.

In the prologue of the book you write that your parents expected you to hitchhike to school.

When my parents wanted me to hitchhike—I went to Calvert Hall—and in private schools and Catholic schools, everybody hitchhiked. It wasn't thought of as an eyebrow-raising thing to tell your children to do then. It should have been. The same perverts were out there that are out there now.

That's what I was wondering. What has changed? I don't spend much time driving on the interstate, but when I did in the 1990s I don't recall seeing many hitchhikers.

I never saw any the whole way to San Francisco—well, I saw one hitchhiker. The last time I saw one in Baltimore, I picked him up. It was the daytime on Eastern Avenue, and I was there innocently—Eastern Avenue didn't used to be an innocent place to pick up hitchhikers, believe me. And he got in the car and immediately started huffing glue. And I said, "Just make yourself comfortable." He offered me some. I said no—it wasn't a Friday night, it was a Tuesday morning or something. If I'm going to huff glue in my 60s, it ain't going to be on a weekday morning. It would have to be a really bad night, late.

What do you think happened to all the hitchhikers? Did more people get cars? Did other forms of transportation become more affordable? Or did we just get more fearful of each other, worried that hitchhikers or the people who pick them up are serial killers?

I don't know—I'm trying to bring it back because it's green, you can get a date. Hitchhiking is always a little sinful, it's always cinematic. You always feel like you're in a movie when you're hitchhiking. I think people were frightened by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and all the movies where hitchhikers are so torturous. And serial killers sometimes do pick up hitchhikers. The type for a serial killer is usually not somebody who is 66—that's why I thought up a serial killer who did go for them [in the fictional "The Worst That Can Happen" section]. All my criminal friends begged me not to do it. They were the most against it.

At the beginning of the "Real Thing" section you mention using AAA to plan the route and you list everything you took with you. Did you do any research about hitchhiking prior to leaving? I ask because I Googled hitchhiking tips and got more than a million results.

My assistants did a lot, but mostly what we looked into was the most moderate time to do it on route 70. And it was the week I did, the last week in May. And the only thing I forgot was that it rains during that time, and we didn't check that. It rained a lot during the first couple of days, which was a nightmare.

But I knew about hitchhiking laws. It's quasi-legal. It depends on where you are, the situation, and the policeman—one cop gave me a ride. I always stood right on the entrance ramp, right before the sign that says it's illegal to go down onto the highway. And police saw me a lot and didn't pull over, maybe because they thought I was an old man hitchhiking. I didn't look that threatening. And when I would see a cop I had a sign that said "writing hitchhiking book." That totally did not work to get people to pick you up, but it worked for cops because they didn't want to get involved in that. And the one [cop] that picked me up ran my name to see if I had any warrants. That was the furthest that went. I had my fame kit, and he looked through that, didn't say anything, and finally said, "Well, it doesn't say you're a professional hitchhiker." So I knew he had a sense of humor. He was very nice.

What prompted the consideration of the best- and worst-case scenarios? Mental preparation?

Yes. I thought, What could this be like? And thank god I wrote these before I did it because I never could have written them afterward. And hitchhiking always involves fantasy. It involves a little bit of fear, a little bit of fantasy, a little bit of an adventure, a little bit of sex, a little bit of everything—no matter if none of that really happens. It's in the air.

So I wanted an adventure, plain and simple. I thought my life was a little too safe, too planned. My every second is organized, every minute of every day, so I thought, Let me see what it would be like to give all that up and see how far this fame goes. It did help sometimes, but many times it had no effect. People thought I was just an old man. They didn't believe me when I told them I was a filmmaker. They thought I was somebody off his meds. It was like I was saying, "Hi, I'm Napoleon"—that's kind of how they reacted. Or, even better, they'd [recognize me] but they didn't ask any follow-up questions because they didn't seem that impressed, which I really loved. I wanted them to talk anyway. I wanted to hear their stories. People who pick up hitchhikers are good people. They've got a sense of humor and they've been through something. They've got stories to tell.

I ask about the best- and worst-case sections because reading through the fiction parts, by the time I got to the end of that section in which you compare Bristol's dog-overrun home to a new circle of hell, I kind of felt like I was reading your version of The Divine Comedy.

For me it felt like all those people in the fictional parts could be in my movies. They are like my movies, that's not that far of a stretch. And nobody gets mad at what I say anymore. To think this was on the New York Times best-seller list for six weeks and I have a magic asshole that sings a duet with Connie Francis? That's mainstream today? Times have changed.

When I was young, my only job was in a bookstore and you could go to jail for a book like that in 1962. Jack Smith showed Flaming Creatures and the police raided the place and took the whole audience away. Times have become very different.

Once you finally set out and get moving, you do a very good job of condensing these trips into compact pieces of writing—and you mention how much time you spend waiting. Were you quite prepared for that amount of time standing by the side of the road? At one point you say you waited for five hours one morning.

Ten hours I was there one day. That is the only thing I never imagined when I imagined the worst that can happen, the tedium of it. And now that it's over I know I got a ride, but today it's really hard to remember that despair. In those moments I was thinking this could take a year. I could be here until the fall.

And it seems that, outside of a few people at the hotels, diners, and convenience stores you encountered along your route, I get the impression that almost everybody who picked you up was pretty nice, friendly, and talkative.

Everybody was lovely. I didn't have a bad ride.

But you're still getting into a stranger's car. Were you able to tell, early on, that this was a nice person—or was there a bit of nervousness every time?

No, I believe in the goodness of people.

I have to confess the renegade builders was my favorite ride.

They were great. They're the only ones where I don't know if they read the book. I guess I have a cellphone number for them, but I left it alone because they didn't want to be discovered, I think. I had a great time with them. They knew I was known for something, but it wasn't until I said I was in one of the Chucky movies (Seed of Chucky, 2004) and they said, "Oh, why didn't you say so?" I had a really long ride with them and the entire ride I had to sit on the glove compartment between the two front seats of a van, which is completely illegal. When we drove past the St. Louis Gateway Arch, they said they had sex in the elevator there and I thought, These are my people. They were great.

OK, the Corvette Kid. How lucky do you have to be to run across a young man with an adventurous streak who is willing to act upon it?

And he had no idea who I was, even after he Googled me. He had never heard of any of my movies. I still talk to him. He has a beautiful new girlfriend, he looks really hot—I think it was good for him. The whole trip was really good for his self-esteem. Why wouldn't any kid do that? Talk about an adventure. I understand why his parents were uptight—and they were really uptight when they heard he went back. Then they really freaked out.

I was going to ask—did you ever meet his parents or send them a copy of the book?

No. I didn't talk to them or anything. Even when the book came out—they'll really freak out if they read the first part. But no, I don't think they're my biggest fans. Although I was completely a good guardian for their son and it was completely innocent. And we laughed about it because we realized what it looked like. But it wasn't—it was an adventure. It was a bromance.

If I counted right it seems it took you nine days to cross the country. Is that good time? That seems like good time to me.

It isn't so bad. It would have taken longer if [the Corvette Kid] didn't come back. He took me through three states, but I eventually got out and gave him the keys to my apartment and said, "Here, go stay at my apartment. I need more chapters for the book." That's when his parents really freaked.

It ends with you in your San Francisco apartment. So what were the first things you wanted to do upon exiting the hobo existence?

I was so shocked to be in real life. We went out that night—he stayed in San Francisco for three days, that's not in the book—and we went out to dinner and went sightseeing. And it was weird. I felt guilty when I would get in a cab. But the weirdest thing was, [news of the hitchhiking] had been online so much that everybody knew and people were telling me, "Glad you made it!" People really gave me warm welcomes. And people offered me rides everywhere.

And I'm just curious: how did you get back to Baltimore? Greyhound bus?

[Laughs] No—the opposite. I went back to New York to the fashion Oscars first-class. I was accepting awards for [Japanese fashion designer] Rei Kawakubo and Johnny Depp, so I gave two speeches. It was the exact opposite going back. And I like both—it's coach I can't handle. I'd rather hitchhike. I'm not being a snob—I didn't fly first-class until I was 45 years old. I paid my coach dues.

You mentioned people were arrested seeing Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures. Over a year back I was doing some research in the papers of the late Johns Hopkins chaplain Chester Wickwire ...

Oh, I love Chester. He helped us when we got arrested on your campus. He was great. If riots happened, you could call him. He was famous nationwide. To me, he was the best thing about Hopkins. I always knew I had a friend there no matter what happened.

I was going to ask you about the arrest but first, his office ran a film series in the 1960s and '70s and Flaming Creatures played here. And reading that made me wonder—in the late 1960s and '70s, where did one go to see non-mainstream movies in Baltimore? I think the Baltimore Film Forum started in 1969 or so, and Hopkins professor Richard Macksey was part of the group that started that. MICA started a Film Festival in 1967, with Hopkins and Goucher joining that effort in '68 and '69, and some part of that I think became the Baltimore Film Festival, which is where I think Pink Flamingos debuted in 1972. But my knowledge of movie-going in Baltimore at the time ends there.

Colleges were the only place you could see them. The best one was at the University of Maryland, called Company Cinemateque. That was really amazing. UMBC had one. And Hopkins was always good at that.

Did you meet former Hopkins Professor Leo Braudy through the local film festival community? I ask because didn't he have a small role in Polyester?

Of course. I met him through the film festival. I love that [playwright Edward] Albee taught at Hopkins. I saw something that I don't think Albee did anywhere else. He read all of his women's parts in character at Hopkins, and I was there and it was brilliant. I don't think he did that anywhere else that I know of.

I always appreciate your movie picks for the Maryland Film Festival, and I was actually living in Dallas when you visited the USA Film Festival there and saw you present Joseph Losey's fantastic Boom! And when the Film Society of Lincoln Center held its recent retrospective for you, you included a number of movies you were jealous you didn't make, including Mai Zetterling's Night Games, which I love ...

You saw that?

I spend a lot of time online. You can actually find a copy on YouTube.

Forty-eight people paid to see it in New York, and I think that's the biggest audience it's ever had. Everything else was packed, but Night Games—nobody's heard of that movie. And it caused a big sensation because Shirley Temple Black walked out in protest when it was at the San Francisco Film Festival. That's what made it famous. But it was great—it's like a Bergman movie gone crazy. I love Night Games, I couldn't believe they found a print.

If you had to group, say, seven of these films together and teach them as a film seminar, what would the class be called?

I had a show on television called John Waters presents Movies that Will Corrupt You. Maybe that. And when I picked the ones for Lincoln Center I purposely didn't choose any that I had picked for the Maryland Film Festival or the Provincetown International Film Festival or any of the ones from my TV show. So I'm always curating weird movies. I had a film festival at the Sydney Opera House called "Double Features From Hell." And opening night was [director Gaspar Noe's] Irreversible and [director Lars von Trier's] Antichrist, together at last. You should have seen that audience. I asked how many people were there on dates. Not one person raised their hand. Every person was alone.

OK, you mentioned your arrest on the Homewood campus in the late 1960s. What happened there?

What happened was we were filming a scene in Mondo Trasho and we didn't ask for permission. I didn't know there was such a thing as a location scout. I figured it was Sunday morning, the students will be asleep. So we just went there. And I can picture right where it is. It's where the old bookshop used to be, that little street that isn't even there anymore. And a security guard saw us and thought we were filming a porn movie, so he called the police. The cops raided the set and they busted all of us, but not Divine. He got away. And he was in a red 1959 Cadillac Eldorado convertible with the top down and a gold lame toreador outfit with a nude man in the car—in November. And they couldn't catch him.

And Hopkins, I think, later was kind of mortified that this even happened because they just didn't know. My father was really mortified because he went to Hopkins and it was a nude man, not a nude woman. He was so furious and mortified. I remember I had to go show my early movies to the DA, and they all thought they were going to see porn movies or something. And it was the most innocent, avant-garde, out-of-focus, jumpy cut movie. They were so disappointed.

When I was in jail, and it was the little prison in Hampden, I just called the ACLU and it happened to be [future Baltimore Circuit Court Judge] Elsbeth Bothe who answered the phone, and she got a famous radical Baltimore attorney to defend us. It was national news, totally unplanned. It was on the cover of Variety. And the judge read to us, "Go behind the door and sin no more"—it became a media joke, the whole thing.

Mark Isherwood, who played the nude hitchhiker, just died this year. I had just heard that, and it was really sad because I remember that day and I hadn't seen him in 25 years. But I don't remember if the Hopkins guard was there to testify—it was all a blur. I don't remember the trauma of my obscenity trial. Now I can look back on it and laugh.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged books