Inventories & Imperatives

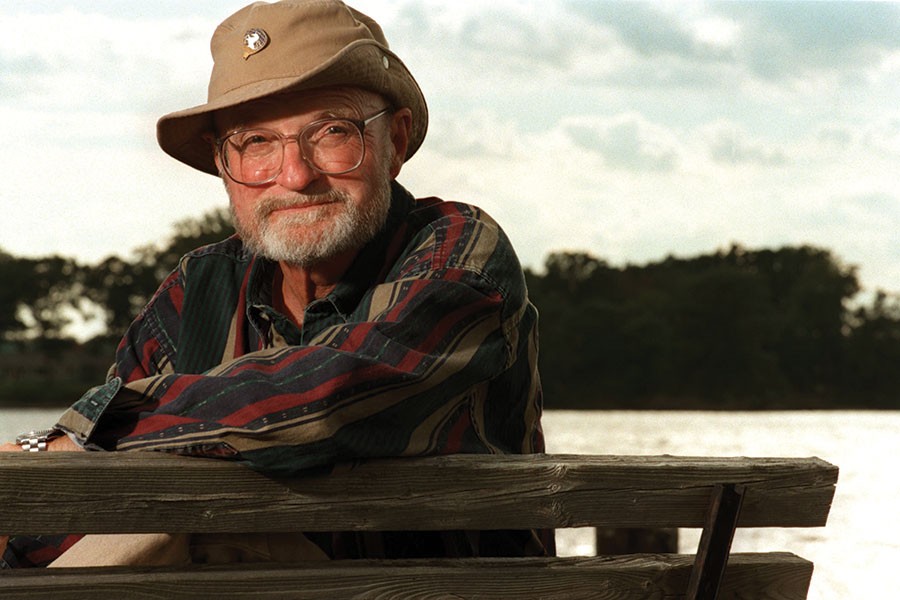

Image caption: John Barth, top left, speaking in the old board room in Shriver Hall, possibly in the early 1970s.

Image credit: Courtesy of the Ferdinand hamburger archives milton s. eisenhower library, Johns hopkins university

On the first day of their first seminar, John Barth would distribute to his graduate students a single sheet titled:?

THE BARE BONES OF LITERATURE IN GENERAL (and fiction in particular).

Prominent was a list:?

NUMBERLESS CONTRADICTORIES (or aesthetic antinomies):?

Windexed language.....versus.......stained glass language

Realism...............".........irrealism

Apollonianism....."....Dionysianism (etc. ad inf.)

The sheet was organized in the spirit of the Panchatantra, divided into numbered subgroups, such as:?

FIVE IMPERATIVES for apprentice writers of literature:

- observe & study the material; "caress the details" ?

- read, no longer innocently, & preferably mas?sively ?

- practice both your specific genre & the general ?rendition of your observations into language ?

- criticize & be criticized, to sharpen your sense of the medium, the rudiments, and aesthetics ?generally ?

- monitor your observations, reading, practice, ?& criticism, in order to identify & build upon your particular strengths and to strengthen or minimize your particular weaknesses ?

JB had a second pamphlet for his graduate ?students, this one sprawling by comparison at three closely typed pages, called DRAMATIC ACTION (praxis) & PLOT (mythos), wherein is found, early on, perhaps JB's most famous literary definition:

Plot = "the incremental perturbation of an unstable homeostatic system and its catastrophic restoration to a complexified equilibrium."

Maximalists & Minimalists

Most of JB's literary descendants, those he influenced but did not teach, trend in a maximalist direction. David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Franzen come to mind. The best of his students, however, trend toward the minimalist. In one graduate seminar, JB had at the table both Mary Robison and Frederick Barthelme, two of the purest of the High Minimalists. And after studying with JB, it became clear why. There didn't seem to be a subject—from particle physics to county fairs—that escaped his close attention. "With 20 minutes of close study, a writer can appear convincing on most any subject," he would say, particularly when he had come upon a deficiency of fact. "Unity of detail" required first "the good detail" itself, and the good detail had to be true. He had no patience for the slapdash or the broad stroke. And if that meant dealing in micromosaic or petit point, so be it.

In the duple nature of all things with their source JB, Frederick Barthelme's younger brother Steven also attended the Writing Seminars and studied with JB. And of all of those two Barthelme brothers' books, the best is the one written in collaboration between the two of them, a narration of their misadventures riverboat gambling on the Biloxi coast. It is titled Double Down.

Jack & Jack

My introduction to JB came by way of John Hawkes, who held a deep admiration for him. One day I called Hawkes for advice about writing programs. After a long sigh, he directed me "down to Baltimore."

I knew of the Johns Hopkins program mainly from Hawkes, who had put a dilemma to me the year before. He had been invited to read at Hopkins and had it from John Updike that JB lived on a "magnificent yacht at the Inner Harbor" and sometimes his guests stayed with him there. Hawkes did not want to be presumptuous by inviting himself to stay aboard JB's vessel, but he was intrigued by its rumored luxury. On the other hand, and worse—this being the way these conversations generally went with Hawkes—he feared that no matter how resplendent JB's "yacht" might be, there was still the matter of sleeping on the water and the rocking that could ensue and other doomsday issues associated with spending a night offshore. Hawkes ended up visiting, but staying onshore, as, of course, no such "magnificent yacht at the Inner Harbor" existed.

After his suggestion, I asked Hawkes if he would write for me a recommendation. Again he sighed. "Can't I just call?" he asked. My hopes sagged. Based on my experience, I didn't gather that "phone call" was one of the preferred methods for academic recommendation. When I arrived in Baltimore the next fall, Stephen Dixon showed me my application file. On the top of the first page was scrawled in JB's inimitable hand: "Jack Hawkes called."

Apollo & Dionysus

In the fall of 1986, JB published a love letter to his wife, Shelly, in Harper's. It was called "Teacher. The Making of a Good One." It is a twinned piece. One aspect concerns JB's thoughts on teaching, comparing his experiences with Shelly's, who by that point was a beloved English instructor at St. Timothy's School in Stevenson, Maryland. The second woven strand was the story of their affair, which began with JB still very much, if unhappily, married. Shelly, "bright eyes, bright smile, nifty orange wool miniskirted dress, beige boots," single and a decade-plus his junior, attended a Boston College reading that JB gave one snowy night. After reintroducing herself—she had been a student of his at Penn State—she slipped a boot into a closing elevator door as JB was being whisked to a private reception and invited herself on the ride upstairs. JB's host, a Jesuit priest, made no objection. After some major flirtation, JB, Shelly, and the aforementioned Jesuit went to a snowy dinner of champagne and oysters. Once the priest had excused himself, Shelly and JB retired to the Charterhouse Motel. The next morning, JB called his host: "No need to fetch me to the airport this morning, Father; I have a ride, thanks."

A few months after publication of the Harper's piece I received a long envelope from my grandmother. Inside I found an article clipped carefully from her Reader's Digest. It was a reprint of the Harper's piece, helpfully retitled "Teacher, Teacher!" The piece was illustrated with a drawing of a young and professorial type standing at a chalkboard and noting a comely student, sweatersetted and wool-skirted, ardently raising her hand. In the interest of brevity, no doubt, all reference to miniskirts, champagne, oysters, the Charterhouse Motel, and a hitched ride upstairs with a Jesuit priest had been omitted.

Barth & Barthomania

At the beginning of the graduate semester, JB would arrive at the seminar room, Gilman 38, carrying his briefcase, which was sufficiently capacious to hold one manila folder, one sleeve of small plastic cups, and two bottles of sparkling wine. Before any business was done, JB uncorked the wine, poured it into the cups, and passed them around. There was just enough in the two bottles for 13 souls to raise a toast.

The last class of our semester together was held at JB and Shelly's house on North Charles Street. Again there was sparkling wine for the 13 of us. In later years, JB would invite Stephen Dixon and me to a lunch at the Johns Hopkins Club at the end of each academic year, where he would start by ordering a bottle of fizz, the necessary way, he felt, to celebrate. The first time I was invited to one of these lunches, I met JB in the Gilman hallway outside his office. "Tris," he said to me, smiling benevolently. "You look like you're dressed for a tenure meeting." When Stephen Dixon arrived moments later, he yanked the carefully arranged white handkerchief from the breast pocket of my blazer and pretended to sneeze in it.

Once I rode down to Washington, D.C., to hear JB give a reading. It was a packed house. At the back, a woman stood beside me holding a yellow bumper sticker:

JOHN BARTH LOVES US

MARYLAND SOCIETY FOR BARTHOMANIA

They had a membership, she told me. They had meetings and they had a newsletter. JB had invited me to have a drink at a hotel across the street after he'd finished signing books. When I got there, I found him seated at a low table in the lounge, surrounded by six or seven other admiring Barthomaniacs, including the woman I'd met at the reading. Like good graduate students, they all had their books out. There was a bottle of champagne, bought by JB in gratitude, standing on the table.

Teacher & Writer

JB wears, and to my knowledge has always worn, eyeglasses. In an early high school photo of him performing with his jazz combo, which included his sister, Jill, on piano, he sits elevated behind his drum kit wearing a heavy pair. There are the jacket photos and the publicity photos, always bespectacled. The lens sizes grow and the lens sizes shrink, but they never shift fundamentally from horned rim. I cannot remember a single instance when I ever saw him without them. He didn't push them up to his forehead for a better glance at a manuscript or, more likely, to squeeze his eye sockets in frustration.

Once, in a meeting with him in his office, the old Gilman 137, I sat in something like a captain's chair, aside the desk JB sat behind. As we talked, my own glasses slipped down my nose. Unthinking, I raised the middle finger of my right hand to scoot them back to their seat, realizing immediately but too late, such was JB's attention during these meetings, the error I had made. Only a moment later, JB raised his own right hand and extended a long index finger, then pressed it to the bridge of his own eyeglasses. It was rebuke and instruction, consolation and kidding. Rarely to this day do I forefinger my glasses back up my nose without remembering it.

Typewriters & Drum Kits

Occasionally, a departmental half-letter would appear taped to the door of JB's office. Once, it advertised a manual typewriter for sale. Lacking one, I purchased it. When I opened it, I realized that it had belonged to Shelly, as it had her name and a Philadelphia address written in thick indelible marker inside the lid. It was in immaculate condition with a fresh ribbon. Another time, there was an advertisement for a bed frame. That, I believe, was free. Finally, there appeared one day, as always in JB's unmistakable hand, an advertisement for the sale of a drum kit.

I later asked Shelly about the final disposition of the drums, and she told me that a nice young kid, just learning to play, had purchased them. I don't know for certain, but I think I can imagine the sort of kit it would have been: a jazz kit and very simple, with, of course, a high hat and a snare; two cymbals, crash and ride; two hanging tom-toms; a bass drum and a floor tom. That kit might very well be the one JB hauled with him to Juilliard, maybe even the one he played onstage with his combo in high school. If so, it seems a terrible loss that it not be part of the John and Shelly Barth collection at the Eisenhower Library. I'd have it on permanent display somewhere central in the Brody Learning Commons, preferably in a clear Perspex box. The title would be: Follow Your Dreams/Don't Let Your Dreams Mislead You.

Teacher & Writer 2

Once, I had the chance to introduce a reading by JB. I did a little counterfactual conditional and proposed that, in some parallel world, had JB not been a writer of such fame, he'd be known equally well for his teaching. I was wrong, of course. JB's fiction will be read and admired long after we are all gone. A teacher's career is written on water. "As a student, for better or worse, I was never personally close to my teachers; as a teacher, I've never been personally close to my students," he wrote in the Harper's piece about Shelly. He eulogized John Hawkes "as an intense, convivial, time-generous, impassioned mentor-coach," almost suggesting the sharp contrast. Though he gladly spent the majority of his life involved in academia, when, at age 60, he retired (for the first time), he registered little regret to be leaving the seminar room. Though, of course, he did return.

One of those seminar days, JB entered Gilman 38 to find three slate chalkboards covered with cochlear swirls and amateurish stick figures. In that time, Contemporary American Letters read the works of the faculty, and Chimera was on the syllabus. Earlier in the day one of the TAs had taken it on himself to graphically explain the book for his class. JB paused by the board for a long moment. He turned to us and, raising a finger, said, "So that's what it means!"

Fiction & Fact

One afternoon, I shuttled over to East Baltimore to hear JB give a reading in the Turner Auditorium. I don't recall exactly the occasion, except that it was a full house and most likely organized by Richard Macksey, the colleague of JB's whose shared Hopkins experience stretched from graduate work to the faculty. After his reading, JB invited questions. One came from an older woman wearing a tweed suit. She observed that the novels often came in pairs, that JB himself was a twin, and that much of his writing had to do with the Chesapeake Bay, where he came from and by way of similar circumstances to those he wrote of often. What she wanted to know, putting a final point to it, was: Wasn't this all a little autobiographical?

After the last of the well-wishers and book-signees had departed, JB and I met at the back of the auditorium and headed out together.

"Doesn't that drive you mad?!" I offered helpfully. "Those naïve questions about autobiography?" He patted my shoulder and smiled. "Tris, I find it best not to bite the hand that feeds me."

Mason & Dixon

In 1997, Thomas Pynchon, a writer often mentioned in the same breath as JB but one who practices in a different orbit altogether, published Mason & Dixon. The novel was noted for its pastiche of 18th-century literary diction, ground covered long before in JB's masterly novel The Sot-Weed Factor. Further, the Mason-Dixon Line, boxing as it does on two sides JB's Tidewater, has forever been an object of fascination for JB. "The Mason-Dixon Line," he has often observed, "runs east and west, but also north and south." Around the time of the publication of Pynchon's novel, I remember heading to a dinner at the Hopkins Club with JB and our guest that evening, fellow alum Russell Baker. As we walked along the President's Garden, I asked JB, "Doesn't Pynchon's book and all its attention bother you, as if this were the first time an American novelist had considered this particular geography or ventured to write an entire novel within its idiom?" "No, Tris, not at all," he replied. "In fact, just recently Pynchon was kind enough to send me an inscribed copy. He wrote: 'To John Barth: Been there, done that.'"

Coda

For the Writing Seminars 40th anniversary celebration, among the invited readers was JB's student Mary Robison, for whom JB gave a warm and celebratory introduction. "I love that man," she said when she climbed the stage. "But I've never been able to tell him that I pronounce my name Rah-bi-son, not Robe-i-son." The crowd laughed and JB smiled kindly, corrected. And we thought: We love him, too. Still do.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged writing seminars, john barth, personal essay