After a voyage of nearly nine years and 3 billion miles—the farthest any space mission has ever traveled to reach its primary target—NASA's New Horizons spacecraft came out of hibernation on Dec. 6 for its long-awaited 2015 encounter with the Pluto system.

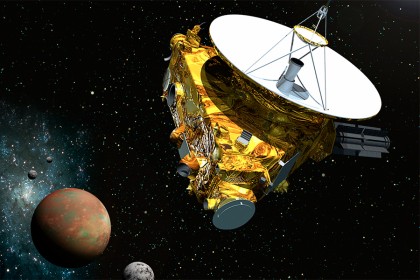

Image caption: Artist's concept of the New Horizons spacecraft as it approaches Pluto and its three moons in the summer of 2015.

Image credit: ohns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Operators at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory verified at 9:53 p.m. that New Horizons, operating on pre-programmed computer commands, had switched from hibernation to "active" mode. Moving at light speed, the radio signal from New Horizons—at that point more than 2.9 billion miles from Earth, and just over 162 million miles from Pluto—needed four hours and 26 minutes to reach NASA's Deep Space Network station in Canberra, Australia.

"This is a watershed event that signals the end of New Horizons crossing of a vast ocean of space to the very frontier of our solar system, and the beginning of the mission's primary objective: the exploration of Pluto and its many moons in 2015," says Alan Stern, the New Horizons principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Since launching on Jan. 19, 2006, New Horizons has spent 1,873 days—about two-thirds of its flight time—in hibernation. Its 18 separate hibernation periods, from mid-2007 to late 2014, ranged from 36 to 202 days in length. The team used hibernation to save wear and tear on spacecraft components and reduce the risk of system failures.

"Technically, this was routine, since the wake-up was a procedure that we'd done many times before," says Glen Fountain, New Horizons project manager at APL. "Symbolically, however, this is a big deal. It means the start of our pre-encounter operations."

The wake-up sequence had been programmed into New Horizons' onboard computer in August and started aboard the spacecraft at 3 p.m. on Dec. 6. About 90 minutes later, New Horizons began transmitting word to Earth on its condition, including the report that it is back in "active" mode.

The New Horizons team was scheduled to spend the next several weeks checking out the spacecraft, making sure its systems and science instruments are operating properly, and continuing to build and test the computer-command sequences that will guide New Horizons through its flight to and reconnaissance of the Pluto system.

With a seven-instrument science payload that includes advanced imaging infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers, a compact multicolor camera, a high-resolution telescopic camera, two powerful particle spectrometers, and a space-dust detector, New Horizons will begin observing the Pluto system on Jan. 15.

New Horizons' closest approach to Pluto will occur on July 14, but plenty of highlights are expected before then, including, by mid-May, views of the Pluto system better than what the mighty Hubble Space Telescope can provide of the dwarf planet and its moons.

"New Horizons is on a journey to a new class of planets we've never seen, in a place we've never been before," says New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of APL. "For decades we thought Pluto was this odd little body on the planetary outskirts; now we know it's really a gateway to an entire region of new worlds in the Kuiper Belt, and New Horizons is going to provide the first close-up look at them.

During hibernation mode, much of the spacecraft was unpowered. The onboard flight computer monitored system health and broadcast a weekly beacon-status tone back to Earth. Onboard sequences sent in advance by mission controllers woke New Horizons two or three times each year to check out critical systems, calibrate instruments, gather some science data, rehearse Pluto-encounter activities, and perform course corrections.

New Horizons pioneered routine cruise-flight hibernation for NASA. Not only has hibernation reduced wear and tear on the spacecraft's electronics, it also lowered operations costs and freed up NASA Deep Space Network tracking and communication resources for other missions.

Like the astronauts on four space shuttle missions, New Horizons "woke up" to English tenor Russell Watson's inspirational "Where My Heart Will Take Me." In fact, to honor New Horizons, Watson recorded a special greeting and version of the song, which was played in mission operations upon confirmation of the spacecraft's wake-up. Listen to it at http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/mp3/wakeup.htm.