In the mid-1960s, two nature lovers in Rochester, New York, concocted a bold, blood-pumping challenge. Inspired by John F. Kennedy's commitment to physical fitness, Waldo Nielsen and Ralph Colt vowed to hike 50 miles in a single day.

At first glance, their decision to make the trek along an abandoned railroad corridor confounds. But Nielsen and Colt, rather reasonably, wanted to avoid having to walk along speeding cars on busy roadways. They also knew a crucial fact about railroads—that in order to successfully get a train to start moving from a standstill, or to prevent a runaway train, rails are built with precise, gradual, and almost imperceptible inclines and descents. For every 50 feet of track, the rail might shift just an inch in height. So even though the duo would still have to tramp over the remaining ballast and rotting ties, rails made the ideal trail for their expedition. They completed the task in just under 20 hours.

Image caption: Bicyclist and outdoors enthusiast Peter Harnik on the Washington & Old Dominion Trail. Harnik co-founded the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy and founded the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land.

Image credit: Marshall Clarke

"Nielsen was a special guy," explains Peter Harnik, A&S '70. "He got really interested in where do the rails lead and how do you find them. He came up with the idea that if you take an old railroad atlas and keep looking further and further back in time, the abandoned tracks leap out at you. The more recent atlases have fewer corridors than the old ones." Nielsen went on to publish a 1974 guidebook of every abandoned U.S. rail corridor he could find, in an effort to inspire others to explore them.

When Harnik co-founded the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy roughly a decade later, in 1985, it was that guidebook that helped him and his colleagues identify unused railroad rights-of-way that could be repurposed as recreation trails. The Conservancy—established shortly after Congress amended Section 8(d) of the National Trails System Act to allow out-of-service rail corridors to be converted to trails until a time when the railroad might need them again for service—has helped create a network of 2,000-plus rail-trails to date, spanning more than 20,000 miles from coast to coast. In rural areas, these rail-trails can be a boon for tourism, drawing bicyclists, runners, skiers, and even snowmobilers who will spend money at nearby restaurants, shops, and lodging. In cities, they reduce traffic and add to the urban canopy. And in all cases, they make for a pleasurable, active experience in nature.

In From Rails to Trails: The Making of America's Active Transportation Network (University of Nebraska Press, 2021), Harnik, now 72, recounts the rich history of bicycling, the rise and fall of railroads, and the grassroots activism that led to the creation of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. Johns Hopkins Magazine caught up with Harnik to learn more about what draws millions outdoors each year to enjoy the long, flat, canopied pathways of America's rail-trail system.

What makes rail-trails so magical?

The engineering on these corridors was just spectacular. I still marvel about it, particularly while riding my bike on rail-trails in hillier areas. Of course, there are rail-trails in Florida and in parts of Indiana where the land is so flat that water doesn't even flow. And they're great! But in an area like along the Torrey Brown Trail in Baltimore, which is a beautiful mix of hills and valleys, you can really understand how much work the railroads did to make a perfect rolling environment for themselves.

They filled in the valleys and they cut through the hillsides, and they found the flattest routes possible, and then made them super graded so that they're gaining just inches in elevation every mile. It makes a wonderful surface to bike on. And as you're pedaling along, you can sort of see just how much spectacular engineering they did. If you look to the side, you can see that at one moment it's 40, 50 feet below you to a ravine, and then not far along, it's a clifftop above you. It's million-dollar engineering for the benefit of the bicycle.

Which one is your favorite?

I've got so many favorites, it's hard to nail any one down. Very often I feel like when I'm out on a particular trail, it's my favorite at the moment. There are all sorts of great trails that appeal to me for a variety of reasons—some are beautiful to ride on, some are beautiful to look at, some are beautiful to think of how they came into being.

How did you discover rail-trails, and what led you to take this up as your life's work?

I grew up in Manhattan and did as much bicycling as possible in the city. Especially in the '60s and '70s, it was extremely challenging and annoying to be dealing with that much traffic and air pollution and all the other issues of being on the street. Anytime we came across a place that didn't have much traffic, we were thrilled. And when Mayor John Lindsay closed portions of Central Park to cars, that was a real revelation.

Eventually, I went to Johns Hopkins, and there was very little opportunity for safe and pleasant bicycling in Baltimore, and then I moved to Washington, D.C., where you had this great, huge park—Rock Creek Park—but it had cars in it. Through a bicycling organization in Washington, I worked with a group of activists to try to get cars out of Rock Creek Park, and we were partially successful—on weekends and things like that. But it was still a constant struggle.

I sort of almost subliminally heard about rails to trails from the Midwest—Wisconsin and Illinois and other faraway places—where people said, "You know these old railroad corridors have been converted to bike trails." And unlike all our efforts with the city, there was no one fighting against the concept, really. In the city, the car drivers looking for parking fought it. Store owners who wanted people to be able to park right in front of their stores fought it. We sort of had everybody against us. But there, since nobody had ever driven on those railroad corridors, there was no assumption that they would be for cars.

I started talking to a wide variety of people—not all bicyclists—who were also interested in rail corridors. Some of them loved railroads. Others had the vision that trains would come back one day, and we could reuse those corridors. Others were walkers, runners, skiers. Even snowmobilers thought, "This would be a cool place to ride snowmobiles." More and more of us started having little discussions about how we could save these corridors so that all of us could use them. That ultimately led to the creation of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, which works with people from all over the country to save their local corridors.

You write that the Conservancy came into being at this perfect time, when all these rails were being abandoned by railroad companies. But at the same time, it was almost late to the game because there were so many you didn't have a chance to save. Can you talk a bit about this race against the clock?

What was happening to the railroad industry for all of the 19th century and a little bit of the 20th century was that more and more railroad tracks were being built all over the country. The system was being overbuilt because there was a lot of competition and no overall plan from the federal government.

Then, when the economics changed and the automobile came along, these railroad companies started losing money and merging and getting rid of excess tracks. The federal government and state governments, for a long time, were protecting local communities from losing their railroad service. They put a lot of roadblocks in the way to keep railroads from abandoning their corridors. So even when they were losing money, they weren't allowed by the government to abandon the corridor.

Finally, after World War II, in the '50s and '60s, there was a sea change in thinking about railroads. With the rise of trucking, the government decided they weren't going to try to force the railroads to keep their tracks. A wave of abandonments started happening.

At the same time, people were starting to ask, if an abandonment occurs, what will happen to the land? Many people said their grandfathers or great-grandfathers had either given or sold their land to the railroads. It was hard to find the original records, but there was a feeling that "we gave it to the railroad, they abandoned it, and now we want it back again. It's ours." And in some cases, that was correct, but in others, no, the railroad owned it and had paid for it or used proper legal methods to get it.

Those two things—that a lot of abandonments were happening and a lot of neighboring landowners felt like the abandoned land should become theirs—made not just bicyclists but also public utility companies realize that they might lose the continuity of all these beautiful, valuable corridors. It became a complicated legalistic argument of who owned the land and what would happen to it. That was all happening as the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy was being created. So we lost the early ones—farmers wanted the land either to plant extra crops or because it made it easier for them to plow across the boundary between two different fields on either side of the track. In suburban and urban areas, people saw them as places for parking or road widening. Suddenly you would lose this beautiful corridor.

Two sentences changed everything, right?

That's right. Congress created the railbanking statute, and it got around all the legal complexities. It said: If a railroad or a neighboring governmental agency thinks there's an opportunity for possible future railroad reactivation, then the corridor can be put into a railbank—a bank for future use. It won't be considered abandoned, and it can be used as a trail in the interim.

When this law passed in 1983, some people said, you know, this is a ruse, this is just a way of stealing the land from the rightful owners. Of course, many of these corridors never did return to railroad use. But with the need to get away from automobile transportation, there's a call for expanding our use of trains. And there's a real crunch on freight trains—freight corridors are getting more and more crowded. So, some of these corridors have indeed become revitalized as rail corridors. It really bears out the looking-ahead, visionary approach of Congress to say, "Let's save these corridors." The country invested so many millions of dollars—billions by today's standards—back in the 19th century in the rail system; it makes sense to save it for future use.

I was really struck by your description in the book of the early days of the Conservancy. It felt almost like a startup with its entrepreneurial spirit.

[Laughs.] Well, we couldn't become Microsoft millionaires because there was no real money in it. But like you said, the entrepreneurial spirit was very similar because we all had this same goal in mind. Going all the way back to the 1890s, bicyclists were the first people talking about paving roads and making decent places for people to bicycle. They were then pushed aside by the automobile for a century and felt like, if we don't save these railroad corridors, there's really nothing left for us to ride on. They felt like this was a last stand.

What was the energy like, working in downtown D.C., not having much money, trying to save these corridors?

We were getting phone calls from two different directions. The first was government agencies telling us about abandonments in really obscure locations. We'd have to pull out the atlas and try to figure out where they were. They weren't using the regular terminology of cities and towns; they were using railroad terminology.

You might have a 40-mile track that went from Philadelphia to coal country. And the railroad wouldn't be abandoning the whole 40 miles. They'd be abandoning 10 miles of it. And we'd look and say, "Wow this is a beautiful location. In the future there may be more abandonments that bring you all the way into town, but for now it's 10 miles in the woods alongside a beautiful stream." Then we'd have to figure out, OK, who lives out there who would care about this? Sometimes it would be an activist or someone with a hiking or biking group. Sometimes it would be the mayor of a small town or the tourism commissioner of a county. And we'd say, "Do you realize the wonderful opportunity for getting people out to your area?" That was one set of calls. And then you'd have local activists calling us saying, "Hey, we just discovered this track, we're not quite sure if it's abandoned, but it's really beautiful and much safer than using the road." So then we'd have to do research for them: Who owns this track? Is it abandoned or not? Is it rusted or is it still a shiny track where it might have one train a week running on it? If the train was still marginally running, we'd help them get in touch with the railroad and start a conversation—How much longer do you think you'll be using this track? What's the likelihood it is going to become abandoned? In some cases, they were very tight-lipped, and in others they would say, "Well, our contract lasts another two years and then it will probably be sold off."

It was very exciting. It was an innovative moment where you were looking for creative people, both on the government side and the private sector side. And what we discovered, gradually over time, was that if you only had a citizen activist but no interested government agency on the local or state level, you were not going to win. And if you only had a government agency—an enlightened parks director or a transportation director—but no citizen activist group promoting the concept, you were also unlikely to win. But if you had what we called the rails-to-trails triangle of a citizen action group pushing for it, a government agency willing to own the land or lease the land or take control of the land, and then a plan of action, you were much more likely to win.

Looking back on this past year and a half, I've been thinking about how we're seeing people rediscover a love for the outdoors as well as for the first time seeing all these street closures in big cities. Are we rethinking how we use our space?

Definitely, definitely. Everything you're saying is in play. Getting away from needing cars for every trip, recreating more, being healthier, re-creating the forest canopy in cities. There are dozens of benefits to saving these corridors and reusing them.

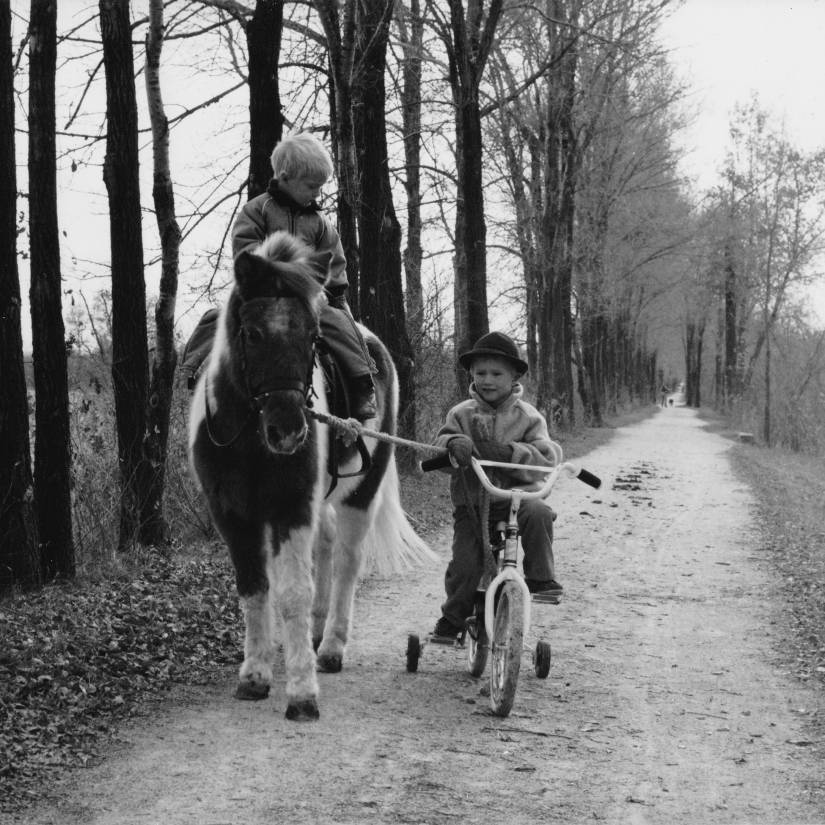

Image caption: Kit and Drew Menke on the Illinois Prairie Path

Image credit: Kevin C. Menke

What do you count as some of your greatest accomplishments while at the Conservancy?

No. 1 is giving the idea viability. Many people thought they were the only ones to have this crazy idea, and then they found out that there were actually others, and there's this national group advocating for this idea. Just the very fact of telling people, "Yes, this is a great idea. It's a viable idea. It's not easy, but we're taking you seriously, and we'll make sure others are taking you seriously, too."

In terms of specifics, there are so many wonderful trails, bridges, and tunnels that have been saved in just about every state. Ninety-nine percent of the people who get out on them in any season, on any form of locomotion, love it and find it memorable, and they bring their friends and families, and it really multiplies the reach of the whole thing.

And then of course, there are stories of someone being paralyzed in an accident and being able to get out in a wheelchair on the trails, or people using them for commuting or exercising.

What are some of your favorite stories you've heard from people using rail-trails?

There's a photograph in the book of two little boys on the Illinois Prairie Path. I just love that picture—two brothers, one on his training wheels, the other on his pony. People say, "If you just put bike lanes on every road you could cover so much more ground. Why don't you just work on bike lanes?" And I say, "There's no way you could put two children, one on a pony, one on a training wheels bicycle, on a four-lane road." When you're dealing with these hardcore cyclists that just want to go very fast and aren't intimidated by cars, they don't realize that a rail-trail serves a lot more than that kind of bicyclist. There are families, and old people with canes, and people in wheelchairs. As I get older and my legs start giving out, I'm looking forward to the different ways I can use a rail-trail.

Find a rail-trail near you on the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy's TrailLink website or app.