Author D. Watkins explores the difference between writing about Baltimore and writing as somebody from Baltimore in the inaugural Donald Bentley Memorial Lecture for the Johns Hopkins Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts on Thursday, April 22. The virtual lecture, titled "Writing Baltimore: A Personal Journey of Lived Experience and Narrative Control," will be livestreamed as part of the Hopkins at Home program from 4 to 5:15 p.m. and will be followed by a conversation with professor of history and English Lawrence Jackson.

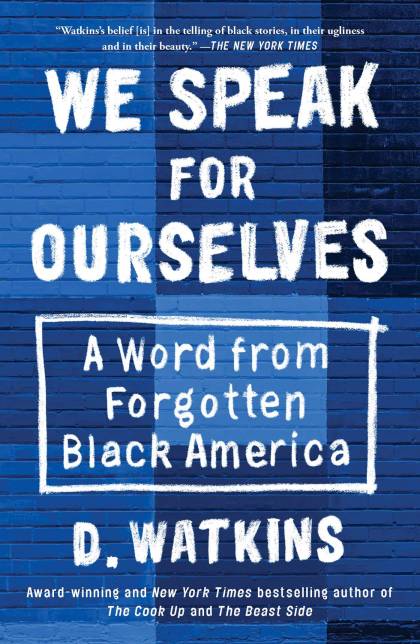

Watkins' sophisticated perspective has shaped a growing body of work that the born-and-raised Baltimore writer, University of Baltimore lecturer, Salon editor-at-large, and Johns Hopkins School of Education alum has produced since the Johns Hopkins Magazine first profiled the then emerging author in 2014. Since then, Watkins has produced three books—his most recent, We Speak for Ourselves, was named the Enoch Pratt Free Library's 2020 One Book Baltimore and provided to all seventh and eighth graders in the city public schools—and matured into one of Salon's sharpest observers of the increasingly complicated overlap of American politics and culture.

Watkins unsurprisingly spent much of his time during the pandemic writing, including two career firsts. He co-wrote a memoir for Baltimore-raised NBA star Carmelo Anthony, Where Tomorrows Aren't Promised, due this fall from Simon & Schuster. And he wrote a screenplay as a member of the writing team for an HBO miniseries being produced by David Simon involving a few of Simon's The Wire creative partners, including crime novelist George Pelecanos, former Baltimore Sun journalist William Zorzi, and former Baltimore City homicide detective Ed Burns. The project is an adaptation of Sun reporter Justin Fenton's We Own This City, about a plainclothes Baltimore Police Department violent-crime task force that robbed suspected drug dealers, sold drugs, planted evidence, and engaged in other corrupt and criminal activities.

Of course, the pandemic meant he worked on all these projects like the rest of us: from inside his home and online. "I ain't gonna lie—I wish I could've gotten a chance to sit in the TV writers' room, you know what I mean?" he says. "Zoom is cool, but you wanna sit in there and talk shit with Ed Burns."

Regular readers of Watkins' columns, however, know how much he enjoyed staying home, thanks to a few people who make regular appearances in his columns these days. He got married in 2019, and the couple welcomed their first child, a daughter, in January 2020. "I'm also lucky because I got to stay home," Watkins continues. "I got to work from home and I got my daughter's first everything, from the first time she giggled to the first time she rolled over to first steps—I got all that. And that's been a major blessing."

The Hub caught up with Watkins to talk about getting writing advice from Taylor Branch, learning to interview celebrities, and why he's not cool enough to get a shoe deal.

In one of our earliest conversations you told me about attending a literary festival in London in 2010, saying you'd meet people and say you're from East Baltimore—and joked about wondering why somebody in London would care what side of Baltimore you're from. One of the themes we talked about was you wanting to show how somebody like yourself could grow up in East Baltimore and be a writer. That came to mind when I was looking at your Instagram and I saw the first two words in your bio, in large capital letters: EAST BALTIMORE. I know few things in life remind you of who you are and where you come from more than having the kind of education and career that's different from how you come up. How has your work experience informed or shaped your identity or mission as a writer now?

I realized that I'm an outsider, and I know this because I've been in the publishing world long enough to know that my core values and how I see the world don't match with the core values of a lot of my peers. I'm in group chats with writers on the come up, trying to figure it out. And I'm in group chats with people that have National Book Awards who are really killing it.

I just see the world in a different way—I don't know if it's because I started writing so late, if I didn't really fall in love with the craft until I was well into my 20s, almost 30, or if it's because of my old job before this. I've learned to be comfortable in that—I know that certain things in my career might not happen for me. I know that my perspective is, at times, gonna make some people feel a certain way, and I'm OK with that.

I didn't realize that until the last book, [We Speak for Ourselves]. It was a fair and honest poke asking if these mainstream movements, like Black Lives Matter, are effective or not. If you're a middle-class Black person and on the news you see this Black kid gets shot, maybe it makes you mad. Maybe you go outside and organize and march for other people. Whereas if you're a poor Black person and you see it, you're mad and frustrated, but to you that happens all the time and you might not make it to the protest. But if it's somebody close to you, you're not trying to draw a picket sign. If it's family, you're not even thinking about that.

We just passed the anniversary of Freddie Gray's killing. Every time a Black person gets killed, there's a whole infrastructure set up around Black death. The TV news comes in, the New York Times pieces start rolling up, and somebody gets a book deal. I feel y'all fighting the struggle from the MSNBC and CNN studios, but what if you ain't got cable?

I wanted to acknowledge that disconnect because it's a problem—you have a mass of people advocating for a bunch of people who didn't ask or who don't know that you're advocating for them. So I wrote about that and people in the media got really, really upset because that's their bag.

So I realized that you have to be comfortable. You can work hard, write what you care about, have a great career and family and life and be chilling—or you can be stressed out because you didn't get that Daily Show call. I drove myself crazy trying to get press for that book, and then I was like, yo, at the end of the day, this don't even matter. And when I embraced that, you know what happened? I was at my house chilling and got a phone call from the Enoch Pratt Free Library. They wanted to make [We Speak] the One Book Baltimore for 2020. That was huge, that was one of the biggest honors of my career because I'm going to be talking to seventh and eighth graders all over the city, many of them going to schools that I went to, talking about these same issues.

I wanted to ask you about your growth as a writer and presence at Salon. You've been there a while now, and if I remember correctly, initially you were doing some writing that became a column, then you started doing some short video pieces, talking to the camera, and then doing interviews—and we're talking interviews with famous people. One of your early pieces was called "Too Poor for Pop Culture," and now you're one of Salon's sharpest commentators on pop culture. I just wanted to hear you talk about building that skill set because the prep research for writing a column versus doing prep for an on-camera interview are two different kinds of work and how you have to spend your time.

When you are a writer and you came up around the time I came up as a Black person, people automatically think you're on this mission to be a voice of the people. And, like, why can't I just write? You get people saying, "This guy wrote an essay about how policing is wrong, so he's gotta be an activist." I'm not an activist. I just don't like police.

The founder of Salon, David Talbot, gave me the book deal for The Beast Side, and it had to be created fast because they had to debut me, and it had to come out before The Cook Up. So I put The Beast Side together real quick—maybe two months at best—and it sold a lot of copies and did way better than everybody thought it would. I think it sold because everybody was trying to read about the other side of policing, and it came out like after Ta-Nehisi Coates' book so people were wondering what else is in Baltimore.

Then I was just chilling because I didn't know what the next move was. Salon had a new CEO coming in, and there was talk of a job at Salon and getting me to move to San Francisco. I went out there and I visited and, nah, I ain't living in San Francisco.

I went back to Salon saying I would stay in Baltimore and work out of the New York office and come to San Francisco whenever they want. The plan was for me to go in as an editor-at-large and do a couple of big articles and then they switched it to me doing hot takes, which wasn't good because my first reaction is always anger. I need some time to process, and I switched to doing more evergreen pieces and I've been enjoying that.

At first they were bringing me to New York three times a week, and then got that down to one time a week. So I was cutting my time up between that and the video side. Salon hired a brilliant producer named Lexie Clinton, who was coming from Morning Joe. She had this idea for writers to interview people versus traditional news hosts, and she was going to use her Rolodex and build up the video side. And she did.

I never thought that I was an interviewer or the person to do that job, but she thought I had the best takes. We started off interviewing people like Melissa Leo, Barry Jenkins, Maggie Gyllenhaal, John Turturro. Lexie thought that I was the person for certain conversations, certain cultural references and themes, that others weren't going to get. With John Turturro, Do the Right Thing is the first film that ever spoke to me—ever. And he was behind-the-scenes on that film and felt that energy, so we're going to connect in a different way and have a good conversation.

And it just became like I was the person to interview anybody who I have an interest in, so Lexie was bringing me up to New York all the time. And sometimes the big, big stars who are kinda touchy, Lexie often gives them to me because she thinks I make them feel comfortable, which is cool. It's difficult because you can only talk for 20 to 30 minutes.

Interviewing people who have been interviewed a lot in their careers is so hard to do well.

Right? I gotta figure out how to get the most impactful questions in in 20 minutes. I would like to get better at it. And I want to get better at other things, too. There's so much studying and work and labor and only so much time. Before starting the Carmelo Anthony book, I had a good talk with Taylor Branch. He's, you know, just a crazy writer. Normally you would think that somebody who writes 2,000-page books, they can take some paragraphs off. He doesn't take lines out. He can just flat out write. He was saying when he wrote Bill Russell's book, he said he had to go live with him to get it done, that he had to get inside Russell's head to make it come across on the page. And I'm like, yeah, I don't think that's going to happen with this.

We had to use Zoom. And Carmelo is a guarded kind of guy, and it took a minute for us to get warmed up. By the time we got warmed up, it felt like it was go time and I had to produce 60,000 to 70,000 words based off our final conversations.

The best thing that happened is that after we were done, I didn't talk to him anymore. I just talked to the publishing company—you know, I have this job to do. So I do my thing and send it along, and I get a text late one night. He texted me. Yo, you got a second? Call me up. And he's saying, "I love the book—it had me laughing and crying. My life is captured," and all this.

He was so happy and that makes me happy. However much the book sells, I know I came in and took the time and had the conversations and the ability to pull that off. And it is something that he is proud of and that, that makes me happy.

That's what I'm going for when I do an interview—if the subject feels comfortable and sees themselves in it. If I can capture that spirit, that's what I'm trying to do. I think it goes back to what we've been talking about how do you validate your career—like, what does your work mean to you? What type of work are you putting in? What are you doing it for? And are you, you know, are you who you say you are?

Could you speak a bit about your Salon pieces over the past few years that deal with health—being healthy, going to the doctor, thinking about mortality a little bit? I ask because as a guy in my 50s who didn't grow up around men who talked about being healthy, in both body and mind, I appreciate the candor you bring to it.

My dad had a lot of health issues the whole of 2018, in the hospital for almost a year straight—a stroke, kidney failure, a kidney transplant, hepatitis, all from just hard living. He started having his kids as a teenager, so he got a chance to spend some time with his kids. I just started having kids, and there's just—like with DMX and the poet Mums, there's a lot of Black dudes in their 40s and 50s just dying. It's not even from the streets, but from how we eat, how we live, not going to the doctors and getting checkups. It's a serious thing.

How have your experiences as a professor informed your awareness of the impact that writing can have on students of all ages?

I think it's a part of an artist's body of work. You want to make books or shows or movies, but at the same time you want to make sure you're sharing those skills because we didn't have that a lot coming up and we still don't. A lot of Baltimore kids today got into photography through Devin Allen. And he's young.

So being a teacher constantly reminds me of not just what I try to pour into the students but what I try to pour into the people who never get a chance to sit in the classroom and who want to do this as a profession: how we connect, how we build, how we share resources, how we network, how we hold each other accountable, and what these things mean. Because I think a lot of people just don't know what these things mean. So, yeah, that's like a real, it's like a real thing for me.

Since you mentioned Devin: When are you gonna get a shoe deal?

[Laughs] I might not be cool enough. Devin, you know, he only wears jeans shirts. Like when we play basketball, it's like a cuff denim shirt. He's cool.

I was real happy for him and I got a chance to work on that campaign. There was a whole art-piece presentation that had a little newspaper, and I wrote a paper. He deserves that type of shine and recognition, and I was glad to see people in the city get behind it, too.

D. Watkins will also be taking part in a Hopkins at Home mini-course beginning April 28.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged d. watkins