A new study led by Johns Hopkins University researchers examines why parents choose not to immunize their children against the sexually transmitted disease human papilloma virus, or HPV. The findings could help public health officials develop new interventions to increase rates of HPV vaccination.

According to the American Sexual Health Association, up to 80 percent of sexually active Americans will be infected with HPV at some point during their lives, with the majority of these infections resolving without symptoms. However, HPV can cause genital warts, benign tumors in the mouth and throat, and certain strains can cause changes in DNA that encourage the formation of cancers in both males and females.

The HPV vaccine, which was approved for females in 2006 and for males in 2009 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, can protect against nine cancer-causing strains of HPV, including cancers of the cervix, vagina, vulva, oropharynx, and anus. Worldwide studies have shown the vaccine to be virtually 100 percent effective and very safe, with the FDA concluding that the vast majority of side effects are minor, and that benefits continue to outweigh adverse events.

Despite efforts to include the HPV vaccine as part of the routine childhood vaccination series, current use of the vaccine in the U.S. remains relatively low. In 2016, the most recent year for which data on vaccination rates are available, only 50 percent of eligible females and 38 percent of eligible males had completed the vaccine series.

"We wanted to better understand why parents choose not to vaccinate their children against HPV, since that information is critical for developing improved public health campaigns and provider messages to increase vaccination rates," says study author Anne Rositch, assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She holds a joint appointment in oncology at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

For the study, which is published online in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers mined data from the 2010–2016 National Immunization Survey-Teen, commonly called the NIS-Teen. The survey collects information from a nationally representative sample of parents about their children's vaccine usage, with vaccine rates verified with information collected from each child's physician.

During those years, the survey included questions about whether parents planned to vaccinate their children against HPV if they hadn't already, and if not, why they were choosing not to. The research team analyzed responses to that specific question, which was asked as an open-ended question to allow parents to name their reasons rather than choosing from a list.

Image credit: Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Rositch and her colleagues—including Anna Beavis and Kimberly Levinson, both assistant professors in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the School of Medicine; and Melinda Krakow, a former master of public health student at the Bloomberg School—sorted the answers into "reason" categories, separating the data by year and by children's gender.

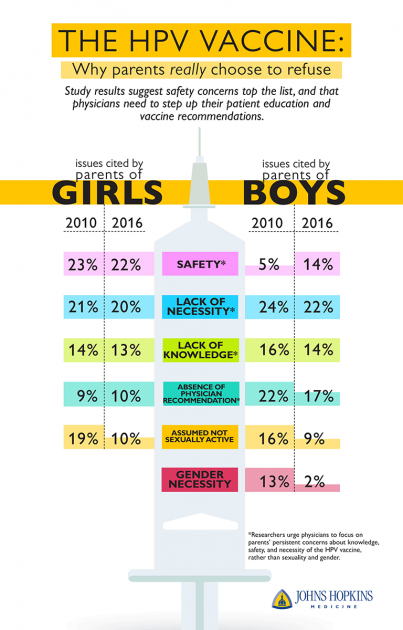

They found that for girls, the top four reasons parents gave for not vaccinating were:

- Perceived safety concerns (cited by 23 percent of parents in 2010 and 22 percent in 2016)

- Perceived lack of necessity (21 percent and 20 percent)

- Lack of knowledge (14 percent and 13 percent)

- No physician recommendation (9 percent and 10 percent).

Those citing their child's lack of sexual activity shrank by nearly half over these years, from 19 percent in 2010 to 10 percent in 2016.

For boys, the top reasons cited by parents for not vaccinating included:

- Perceived lack of necessity (24 percent and 22 percent)

- No physician recommendation (22 percent and 17 percent)

- Lack of knowledge (16 percent and 14 percent)

- Child's lack of sexual activity (16 percent and 9 percent)

Notably, beliefs about males not needing the vaccine decreased over time from 13 percent in 2010 to 2 percent in 2016. However, concerns about safety for males increased from 5 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2016. The researchers are not sure why that is, but do note that less than 1 percent of parents of males from 2010 to 2016 reported anti-vaccination concerns as a reason to not vaccinate their child. The researchers say it's unlikely that exposure to false anti-vaccination information contributed to these safety concerns.

Beavis says that their findings demonstrate that parents are less concerned with the HPV vaccine's relation to gender and sexual activity, and that public health campaigns should focus on persistent concerns about safety and necessity of the vaccine for both boys and girls in order to be responsive to parents' true concerns. She suggests that doctors who commonly administer the HPV vaccine, including family practice physicians, obstetricians/gynecologists, and pediatricians, should focus on the fact that the HPV vaccine has enormous potential to prevent cancers and has a strong safety profile from more than a decade of vaccine administration.

These physicians may also be more likely to broach the subject with parents and recommend the vaccine if the doctors themselves better understand that relatively few parents avoid vaccinating due to concerns over sexual activity.

"We think all physicians need to be champions of this vaccine that has the potential to prevent tens of thousands of cases of cancers each year," Beavis says. "Providing a strong recommendation is a powerful way to improve vaccination rates."

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the HPV vaccine be included with routine immunizations that occur at age 11 or 12. The CDC notes that vaccination can be started as early as age 9 and occur as late as 26, and the FDA recently approved certain versions of the vaccine for individuals up to age 45.

Posted in Health

Tagged vaccines, hpv, sexually transmitted diseases, adolescents