Joseph Barnes and his classmates at Highlandtown Elementary/Middle School saw a problem in their neighborhood—and smelled it too: people weren't picking up after their dogs.

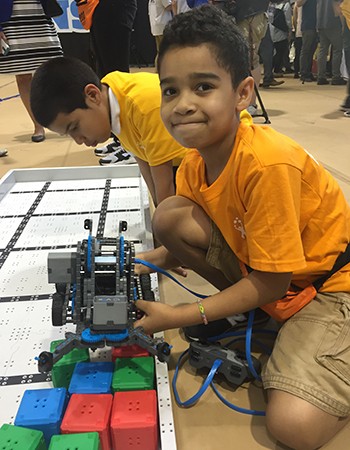

Image caption: Third-grader Joseph Barnes developed a robot to help clean up his neighborhood sidewalks

Image credit: Jill Rosen

They used science to try to fix it, creating a poop-scooping robot that they showed off Wednesday night at a showcase for such inventions, the culmination of a five-year pilot program created by Johns Hopkins University to strengthen science, technology, engineering, and math education. The program is called STEM Achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools, or SABES.

"I made stuff before, but I was very young and I didn't understand that much until I got with SABES," said Joseph, a third-grader. "SABES made me better at building things, and it made me understand what I could do."

With a $7.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation in 2012, the Johns Hopkins schools of Engineering and Education teamed up with Baltimore City Public Schools to launch the pilot, which involved a three-pronged approach.

First, thoroughly train teachers in best practices. Then, give students a rigorous, engaging, and hands-on curriculum. And finally, bolster what's learned in the classroom with after-school programming that shows students how science can affect their neighborhoods and their lives.

This is the fifth and final year of the pilot, which has reached more than 2,200 Baltimore students and trained 147 city teachers. Research suggests students who've taken the program are more confident and interested in science and engineering. For instance, after completing the program, the number of students interested in becoming an engineer jumped 27 percent.

"The results show kids are becoming better critical thinkers and they really understand the engineering process," said Christine Newman, assistant dean of engineering educational outreach at Johns Hopkins. "In the program, they try and fail and improve and succeed. And that gives them the resilience they need in other parts of their lives."

Students from nine Baltimore City elementary schools participated in the program and the capstone event to reveal creations they dreamed up and then built to solve problems they noticed in their neighborhoods. This year, in addition to the poop-scooping robot, kids created a portable shelter for the homeless and a "bird condo," to attract and give refuge to desirable birds.

Jadyn Seldon, a fifth-grader at Dr. Bernard Harris Sr. Elementary who her teacher calls one of his best students, helped design the condo.

"It's so our neighborhood would look brighter and more colorful," Jadyn said. "And so the birds have somewhere to live."

Its creators hope the program has given a boost to students who might otherwise be insufficiently prepared to pursue careers in science—job opportunities that are expected to grow in the future. They say it's critical to spark interest in science early, and equally critical to devise tested educational models to do it.

Jadyn's teacher, Ron Davis, said Jadyn and her classmates seem to love the hands-on elements of SABES—like working out the physics of a pinball machine and trying to design a house that could withstand an earthquake.

"Kids love building and making things," he said. "We have so many different types of learners and this allows kids to be themselves while promoting learning."

Posted in Science+Technology, Community

Tagged community, stem, sabes, baltimore city public schools