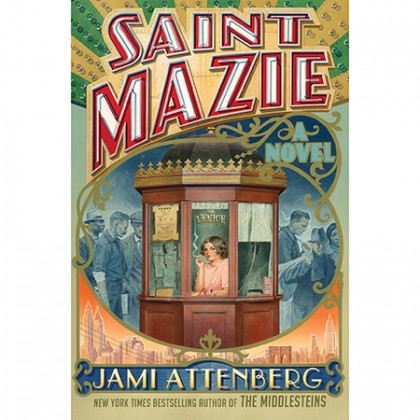

Neighbor, sister, lover—these are the people Jami Attenberg dreamed of chatting with while writing her new novel, Saint Mazie (Grand Central, 2015). The friends and family of Mazie Phillips Gordon, however, are no longer of this earth. She was the proprietor of and ticket taker for the Venice Theater in Manhattan's Bowery neighborhood in the 1920s and '30s, and one of the colorful city characters captured by The New Yorker's Joseph Mitchell in a 1940 profile simply titled "Mazie" (later collected in the Mitchell anthology Up in the Old Hotel). As seen and heard through Mitchell's discerning eyes and bent ears, she had a frightening voice, kept two tightly rolled copies of the trashy True Romance magazine rubber-banded together to thwack drunks caught snoring during a picture, and worked a day-into-night shift that "would kill most women." She was close friends with two nuns and a monsignor in Lower Manhattan and did everything she could to aid and care for the broke, unemployed, homeless, and discarded men whom hard times had deposited on the Bowery's skid row.

"She's a little more rough around the edges in [Mitchell's] essay, and she's really tough," Attenberg, A&S '93, says of Mazie. "But she engages in all these incredibly caring acts. I was struck by her complexity instantly, and there's a lot of mystery that surrounds her, too." Aside from Mitchell's profile (she later discovered he mentions her in an earlier essay, as well), Attenberg dug up Mazie's 1964 New York Times obituary and an article from when she retired from the movie theater. "In that article, she said she was going to write her memoirs—which either never got written or got written and never got published. And I thought, 'I really want to read those memoirs. So why don't I write them?'"

And so Attenberg began her fifth novel, Saint Mazie. But about 80 pages into the draft, she hit a wall. This woman who so fascinated her felt distant on the page. "I was frustrated because I didn't have all the information about her that I wanted to have," Attenberg says. "I didn't even have a picture of her. I wished I could ask people about her. I woke up in the middle of the night and wrote down, 'neighbor, sister, lover'—those are the top three people I would like to question about her. And I realized I could just invent them."

Also see: 'Saint Mazie,' by Jami Attenberg (The New York Times Book Review)

That decision led to Saint Mazie becoming the intimate, polyphonous, and engaging novel that it is. Attenberg wrote it as a collection of excerpts from Mazie's unpublished memoir, entries from Mazie's diary from 1907 through 1939, and the memories of people who knew her, sculpting Mazie through this archaeological symphony of voices. Details from early 20th‑century New York seep into these accounts. In addition to Mitchell's Up in the Old Hotel, Attenberg read John Kasson's Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century, and consulted Princeton University history Professor Emily Thompson's multimedia website, The Roaring Twenties, which houses recordings from the era. She also read Only Yesterday, a history of the 1920s written by Harper's magazine writer and editor Frederick Lewis Allen and published in 1931, which provided a sense of what people of the '30s remembered of the '20s.

She wanted to consume just enough research to prime and focus her imagination. Mazie "felt very modern to me," Attenberg says. "She felt very independent and assertive, she didn't take crap from anybody, and when she saw a problem she just fixed it. And I thought she could be somebody who we need to read about today. I wanted [the book] to feel like you were right there with her in the moment."

Aiming for that sense of urgency fits right into Attenberg's novelistic strength. In previous books such as The Melting Season and The Middlesteins, Attenberg showcased a patient, unflinching empathy for her narrators, allowing them to feel life's everyday extremes intensely. It's a generosity she grants to Mazie, who, even at a young age, forms her own ideas about living. Attenberg has Mazie complain about her older sister in her diary: "She doesn't see shimmering cobblestones in the moonlight, she just wonders why the city won't put in another street lamp already. . . . She sees a taxi whisking by and she thinks, what's the hurry? And I think, where's the party?"

These imagined thoughts allow Attenberg to construct a sense of how Mazie envisioned herself, sketching an interior life for the Venice Theater figure that no amount of reporting could access. And, in some cases, these private moments assign personal meaning to the casual observations that people used to portray Mazie. "To me she's a hero," Attenberg says. "I really thought of this book as her origin story. She's described in the articles written about her—she wore this floppy hat, dangling bracelets, and carried a walking stick. And I thought, 'That's her Spider-Man mask.' That's her costume. So I wanted to make sure you know where these items came from."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged jami attenberg, new yorker, mazie phillips gordon, fiction