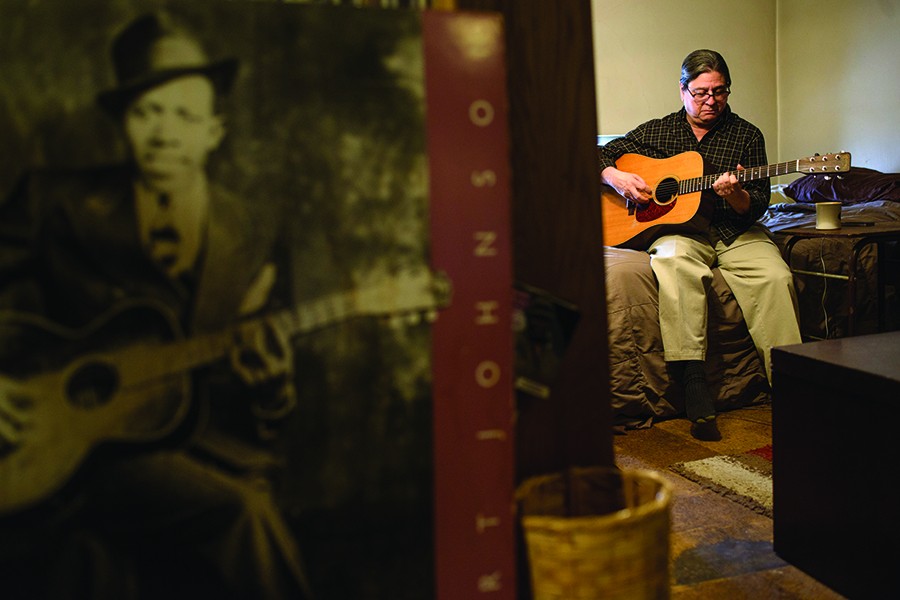

Larry Hoffman does not mind being teasingly called the blackest white guy in Baltimore. He is likely to take it as a compliment. All his life, he has been besotted by music, especially one of the two great African-American musical forms, the blues. He has played blues guitar, performed with some of the great old bluesmen, studied the blues with a scholar's rigor, produced blues records, and been nominated for a Grammy for his blues liner notes. For the last 30 years, he has worked at composing original blues music, not quotes or transpositions, for the classical stage, for string quartets and other chamber ensembles. What Bartok and Janáček and Copland did with folk melodies, what Gershwin did with jazz, Hoffman has been doing with the blues, to scant notice. He was 10 years old when he discovered he would rather play the ukulele at summer camp than swim with the other kids in an icy lake, and if the great question of human existence is how to live, then Hoffman's great question has been how to live through music. He is now 68 years old and living in a tiny, overstuffed, shabby apartment because he has never made a dime as a composer, and he does not care. Everything in his life is as it is so he can create music. Asked if he is happy with that life, he shoots back an unequivocal one-word response: "Thrilled."

Hoffman, Peab '79, '83 (MM), says he feels guilty when he is not composing, though he admits that after attending a chamber concert he will invest many hours in writing an unpaid review of it for the Ticketmaster website. It does not take much to launch him on a passionate and frequently profane disquisition about the injustice of white blues imitators making the money that should have gone to black bluesmen, or about the vapidity of minimalism or how the Pulitzer Prize in music no longer means anything or how jazz-rock fusion killed jazz. Once in conversation about his creative process, I made the mistake of saying "when you're messing around with part of a new composition—" and Hoffman cut me off. "I never mess around," he said. "Wrong words, buddy." What has marked his life is a decades-long uncompromising search for what feels like his own authentic music. He believes he has found it. Now if only he could find an audience.

If you are a contemporary composer and your name is not John Adams or Philip Glass, one of your biggest challenges is to get anyone to record and perform your music. Hoffman does have a CD, Works of Larry Hoffman—Contemporary American Music but he produced and paid for it himself in 2011. Few of his pieces receive more than one performance, and many have never been heard by anyone but friends who have listened to them played by his computer. His String Quartet #1: The Blues has been performed in Baltimore, Washington, San Antonio, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Sweden, but that is unusual for him. Asked how much money his compositions have earned, Hoffman thinks for a moment and then says, "I got a $17 royalty check for Music for Six Percussionists back in the 1980s." He receives the occasional commission—his Three Songs for Bluesman and Orchestra was commissioned and performed by the Chicago Sinfonietta—and some earnings from his CD, but that does not amount to much. Taped over his desk in his apartment is a quotation attributed to Hunter S. Thompson: "The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There's also a negative side." (That quote is all over the Internet, but Thompson never said it. He wrote something similar to the first sentence in a San Francisco Examiner column in 1985, but he was talking about television.)

The first string quartet has been performed the most, probably because it is an accessible, clever, artfully structured alchemy of sexy blues and atonal writing for strings. It is composed in arch form: The piece progresses through its opening sections to a midpoint, after which the first sections repeat in reverse order. It opens with four choruses of original 12-bar blues music that make you want to dance. Next comes a section of call-and-response interplay between cello and violins based on an African-American prison song called "18 Hammers," sung by Johnny Lee Moore on one of folklorist Alan Lomax's field recordings. On the first and third beats, there is a percussive thwik of plucked strings to suggest a chain gang's hammers striking rock. After a short bridge composed as a fugato—the rhythmic structure came to Hoffman when he was out having drinks with friends; he sketched it out on paper in a corner of the restaurant—the prison song reappears, followed by a centerpiece that is the most atonal music in the composition but still has a bluesy lope to it at the beginning. From that keystone section, everything reappears, with some compositional variation, in reverse order, ending with the appealing shuffling blues that opened the piece.

Hoffman does not know of anyone else working with original blues composed for classical ensembles. "It's been OK to do that with jazz," he says. "But that hasn't been the case with blues, because blues has always been despised as low-caste music. Jazz has a certain panache, a substance and sheen of intellectuality and hipness." William Ferris, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities and current associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, uses the piece when he teaches courses on Southern music. "I point out how this music, from ballads to work songs to blues and country, inspires classical music, that there is a very clear connection," he says. "We play fiddle tunes that Aaron Copland used in his work and we play work chants that Larry uses in his work, so you get to see a very clear line of movement from one to the other. And students, once they hear that, never look at classical music in quite the same way again."

Ferris has known Hoffman for 20 years and says, "He has produced an amazing body of work. I've tried to find him support over the years to underwrite compositions and their performance. I wish I could have done more for him. I think he's a great composer and what he's doing for American music is unique and critical to how we understand our heritage."

The blues and classical music are inextricably skeined in Hoffman's life. He came upon the former as a college freshman, but the first music that entranced him was in Hebrew. On Saturdays in the 1950s, Elmer and Mildred Pearl Hoffman would walk Larry and his older brother, Bennett, from their house in the Reservoir Hill section of Baltimore to Chizuk Amuno synagogue (now Beth Am), where Larry hummed along with the choir. When he was 5, the producers of a local Baltimore television show called Candy Corner put him on the air singing "All I Want for Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth." They asked him to cover his own front teeth with Black Jack chewing gum as a sight gag. "I thought that song was stupid, even at age 5," Hoffman recalls, "and then I had to chew this licorice gum, which I quickly spat on the floor. Talk about a wiseguy."

The Hoffman brothers remember little encouragement of music in their household. Bennett points out that their maternal grandfather was an immigrant tailor from Latvia who lost his clothing business in the Great Depression, an experience that marked their mother. Bennett says, "In the world our parents were coming from, music was a hobby, not what you would pursue as a career." There was a piano in the house that nobody played except for a black maid who showed young Larry how to tap out "St. Louis Blues." When Hoffman was 7, his parents did hire a piano teacher, but the boy preferred improvisation to learning to read music, and after a few lessons the teacher declared him unteachable and did not come back.

When Hoffman was 10, Elmer and Mildred sent him to summer camp in Maine. There was a counselor at the camp who had brought a ukulele with him, and when the other kids went off to swim, Hoffman would slip away and find the instrument and play it. When he returned to Baltimore, he saved his allowance for the $8.50 needed to purchase his own ukulele, and soon he was strumming and arranging vocal parts for a third-grade Everly Brothers cover band. People who knew him then recall his fine voice.

Except for the grandfather's tailoring, the Hoffman family trade was dentistry. Hoffman's father, paternal grandfather, uncle, and cousin all were dentists, and one of his grandfather's patients was Ted Martini, founder of Ted's Musicians Shop, which still exists in Baltimore. When he was 12, Hoffman started renting a different instrument from Ted's every week—strings, reeds, a tenor sax on which he found the melody for "April in Paris," anything just to try them all out. (This would suggest more parental encouragement than the Hoffman brothers remember.) "Larry is one of the few people I know who never really wanted to do anything else," Bennett says. "He was always all about music."

In middle school, Hoffman took up banjo, passing on guitar for the time being because guitar seemed too cowboyish, too Gene Autry, and he wanted to learn songs by Earl Scruggs and other banjo pickers. He might not have cared to read music, but he enjoyed reading about music, and soon began perusing issues of Sing Out! and The Little Sandy Review to learn the lyrics of folk songs. His life as a music scholar had begun and he started digging deep into the history of whatever interested him. In those days, McMechen Street in Baltimore had a record store called the HiFi Shop, and the adolescent Hoffman would dig through the bins looking for rarities. He bought obscure 45s by mail order and pored over the liner notes of new releases on the Folkways label. Years later, he discovered the great collections of folk musicologist Harry Smith and began to realize that the popular folk singers and pickers who he thought had created this music actually had cadged tunes and lyrics from progenitors like the Skillet Lickers, Doc Boggs, and Blind Lemon Jefferson. Music had a history and Hoffman discovered that he loved delving into it.

By 14 he was playing a guitar, Gene Autry be damned. He kept it at the foot of his bed. He recalls it as the first thing he saw upon opening his eyes in the morning and the last thing he saw at night. He would go into his father's downstairs workshop and play at 4:30 in the morning, which his father did not always appreciate. By high school at Baltimore City College, he was playing guitar, banjo, and autoharp in a folk group, and singing harmony. He says the first Bob Dylan album haunted him. When he was 17, he formed a short-lived trio called Larry, Larry, and Chuck with a pair of college students, Larry Miller and Chuck Aaron. "We argued a lot," Aaron says. "We used to fight over arrangements and stuff like that. He was the youngest one, so he got outvoted. In retrospect, we probably should have listened to him a little more." A group of girls, including Aaron's future wife, would listen to the band rehearse. They giggled so much the musicians called them the High Frequencies. There was a club in town called The Flambeau and it offered the band a Wednesday night gig. Not on a school night, his mother ruled.

After high school, Hoffman wanted to go to college at the University of Chicago or New York University. No, said his father, all you'll do there is play music and chase girls. The University of Virginia was all male in 1963 and that's where his father sent him. Hoffman hated it. "What was there to like?" he recalls, all frat boys in blue blazers and neckties. He pledged at two fraternities just to eat as much free food as he could before they caught on that he did not actually intend to join. He came across pianos on campus that carried warnings—NO BLUES OR JAZZ ARE TO BE PLAYED ON THESE PIANOS AT ANY TIME. "Oh yeah," he recalls of his time there, "it was great."

Then he ran into Paul Clayton. Clayton was a musician and musicologist who had roamed the hills of Virginia and North Carolina collecting traditional songs and making field recordings. He had made albums of his own for Folkways and Elektra and was a mentor of Bob Dylan. Clayton hosted music parties at his house outside Charlottesville, and Hoffman began to attend and build a local reputation as a player. Ron Becker was two years older than Hoffman and had known him a little in high school. Now they were both at UVA and became close friends. "Lots of other people had guitars, but he was actually really good," Becker recalls. "He was a serious guy; it wasn't just fooling around." Touring musicians would pass through Charlottesville and make stops at Clayton's house, folkies and bluesmen, and Hoffman soaked up their music. Around this time, he began listening to old blues from the 1920s and 1930s—rough, spooky music by people like Mississippi John Hurt and Robert Johnson.

He spent the summer of 1965 in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where a club called the Blues Bag hired him to open for touring acts like John Hammond, Tom Rush, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and the great Delta blues player Skip James. This led to an encounter that would reverberate in Hoffman's later life. He was backstage at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island at the invitation of James, who invited Hoffman to join him onstage for a duet and a set of his own. This was a tremendous compliment and an extraordinary opportunity, but another tough old Delta player, Bukka White, was standing nearby and overheard the conversation. He shot Hoffman a look. "That look meant, 'Yeah, where'd you come from, you privileged motherfucker,'" Hoffman recalls. Chastened by White's glance, he declined James' invitation and recalls this as the moment when he realized that no matter how well he sang or played, he would never be an authentic bluesman.

The blues can be a touchy subject for Hoffman. In 1990, he wrote a guest editorial for Guitar Player magazine titled "At the Crossroads." Alongside an absurd photograph of him in mustache, jacket, and tie and holding a piece of sheet music—he says he looks like an Iranian sportscaster—Hoffman wrote, "Blues is the profound and glorious musical expression of the triumphant survival of the black race in America. ... How then does the white man come to possess the qualifications to express this unique, ethno-musical identity? In fact, he must pretend." He went on to write, "It is absurd to think that the lifeblood of blues could be extended by anyone who, in essence, could never be anything more than a convincing, expressive copyist. ... We have true living bluesmen trying desperately to compete with the white Xerox machines who have usurped the market."

The editor of Guitar Player, Jas Obrecht, told him that no piece in the magazine's history ever generated so much mail, most of it negative. But the screed brought Hoffman to the attention of the blues community. He began writing for publications like Living Blues and King Biscuit Time. The Smithsonian hired him to write the liner notes— actually an 89-page booklet—for its comprehensive CD collection Mean Old World: The Blues from 1940 to 1994, which earned him a Grammy nomination. He wrote the exhaustive notes to accompany the recordings for Martin Scorsese's documentary series Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues. In the 1990s, Hoffman began producing records, first for Arkansas bluesman John Weston, then for Corey Harris. Hoffman had discovered Harris playing on the street outside the King Biscuit Festival in Helena, Arkansas, and tried to convince the festival organizers to put him on the stage, to no avail. Months later, they encountered each other again in New York and Hoffman offered to produce a recording of his acoustic blues. The result was Between Midnight and Day, which Hoffman brought to Alligator Records, where it won the 1995 Living Blues Critics' Poll Award for best traditional blues album. Two years later, Hoffman produced Harris' second recording, Fish Ain't Bitin', named the best acoustic blues album of 1997 by the Blues Foundation.

Hoffman dismisses almost every white blues musician of the last 50 years. "There have been talented white musicians who have played the blues," he says. "But that doesn't make them bluesmen. That makes them talented white musicians who played the blues." It is a matter of social justice, he says, and authenticity that no white player will ever possess. Recalling his decision to not appear on the Newport Folk Festival stage with Skip James, he says, "I could play the blues. But I could not be the blues." To continue making music, he would have to find his own authentic form. Not just some kind of music he enjoyed making, but music he could be.

He persevered at the University of Virginia for more than three years as an English major. "I loved writing," he remembers. "But I thought I'd probably end up being a lawyer." And then one day he just took off. Becker says, "It's not like he flunked out. He simply left." Hoffman's brother, Bennett, had moved to San Francisco, and he went out to see him during Christmas vacation. A club in North Beach hosted an open mic night, and Hoffman played. Afterward, the club's owner tapped him on the shoulder and said, "If you want a gig here, you got it." So Hoffman quit college and moved to San Francisco. His father had sent him to UVA so he would not play music and chase girls. Now he was a UVA dropout in San Francisco at the height of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture and creative explosion, playing music and chasing girls.

He stayed for a few years, then returned to Baltimore. By this point, Hoffman had decided to study jazz, the other great African-American musical form, and was driving to Philadelphia once a week for lessons with Dennis Sandole, who had taught, among others, John Coltrane. In typical fashion, Hoffman began learning everything he could about jazz, but once again came to feel like the white guy trespassing on black cultural turf. He was 26 years old, making a few bucks teaching and playing guitar in strip joints on the Block, Baltimore's famous adult entertainment district, determined to make music his life but without direction.

Then, he says, he heard Johannes Brahms' Fourth Symphony. "That changed my life. I realized that what I needed to be was a composer. It just hit me—that's it; that's the whole solution. That's the way I can be genuine in music. I went to the library and took out every music theory book that I could carry and taught myself as much as I could. Then I got with Spencer."

Spencer was W. Spencer Huffman, who had taught composition at Peabody Conservatory for many years and by that time had private students. Hoffman recalls lessons where the teacher would bang his pipe on the piano when he heard something wrong and growl, "Do you want to be a dumb bastard all your life?" After a few years of working with Huffman, he began private study with Ray Sprenkle, who was on the Peabody faculty. "I thought he was a very talented guy," Sprenkle says. "What impressed me was the way he sees life. Everything gets translated for him through music. You don't meet many people like that."

Sprenkle urged Hoffman to apply to the conservatory. Hoffman remembers, "At my audition, one of the faculty members said, 'You're 29. What have you been doing for 10 years?' I said, 'I've been a musician. What have you been doing?'" Robert Hall Lewis of the composition faculty said he'd take him on, so Peabody admitted him. "I was intimidated. Then they gave me a theory test, and after that they said, '[You already know so much] we can start you in your fourth year and put you through here in a year.'" But he did not want to race through the conservatory. "I said, 'I'm here to study music, not to get out of school.' They didn't know what to make of me."

As a composition student, he wrote a theme and variations for cello and piano that was performed at the Baltimore Museum of Art. He wrote Music for Six Percussionists, and it placed third in a national competition sponsored by the Percussive Arts Society. His master's thesis composition was performed by the Peabody Orchestra. Robert Hall Lewis later said Hoffman was the most talented student he'd ever had, and people at the conservatory urged him to continue his study and earn a doctorate, but he declined. He did not see how that would help him become a better composer.

For all his stated determination to write classical music, he was diverted for most of the next 15 years by writing about and producing blues music, and by teaching. He started a jazz program at Peabody Prep and taught theory, music history, and other courses, and founded an inner-city jazz program with Lynn Taylor Hebden, who was director of the Prep. Finally, friends of his, including Hebden and John Locke, a Peabody classmate who is now a percussionist with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, prevailed upon him to resume writing music. "I said, 'All you're doing is avoiding composing,'" Locke recalls. "You're doing everything else than what you should be doing. No one else has taken this American art form, the blues, and developed it for a classical form, and I think it needs to be done. Later he called me and said, 'Locke! I hope you're happy! I'm in composer hell! I'm suffering here! You've ruined my life!'"

He wrote String Quartet #1: The Blues, and admits now that he secretly hoped it would be a failure. "Perhaps I really didn't hope that, but I just realized how much aggravation lay ahead of me as a composer," he says. "If it failed, I could leave my compositional dreams behind and continue as a blues producer, historian, and lecturer." But the piece was not a failure, so he wrote another blues piece, this one for wind quintet. He composed Blues Suite for Violoncello Solo, which was recorded by Baltimore Symphony cellist Kristin Ostling. Getting up on stage to play the blues with Skip James had felt wrong, but this felt right, because now, he says, he was not a white man trying to be a blues musician. He was being what he truly was—a blues-besotted classical composer writing the music he felt called to write. "As much as any white guy I know, I've shared experiences with the authentic black players, as a player, as a producer, as a writer, as a friend, as a supporter," he says. "I am not trying to be a bluesman. I am composing American music that brings the blues into the concert arena."

Not everything he writes now incorporates the blues. On a Saturday morning at Baltimore's Second Presbyterian Church, Hoffman attends the last rehearsal of his Piano Trio #1, which will premiere the next night. At 10:15 in the morning, pianist Choo Choo Hu glides through the opening run of notes. Hoffman follows his score, jotting on a piece of yellow foolscap as Hu and the string players, Ostling and violinist Kenneth Goldstein, who is also from the Baltimore Symphony, work through the piece. There is one brief stretch in which the cello part hints at a walking bass line, but that is about it for bluesiness. After the first run-through, Hoffman applauds and Ostling notes that she made a mistake in one section. The musicians play the piece two more times, and everyone agrees that's satisfactory. Ostling says, "I figured that one part out. Now I'm gonna screw something else up." "You're hard on yourself," Hoffman tells her.

The next evening, a couple of hundred people ignore falling snow and slick roads and attend the concert, part of a chamber music series hosted by the church every year. Hoffman is wearing the same jeans and untucked plaid shirt he wore to the rehearsal the day before, augmented for the premiere by a sports jacket. The audience is attentive, the players do a good job with the piece, and after the performance Hoffman is happy for the rare occasion of hearing someone play his music.

He concedes he has done little to advance himself in the business part of the music business. "Some people are very good at that," he says. "But that's not anything I want to do." He likes to tell the story of the time he turned down an offer to compose the score for the movie Violets Are Blue, which was filming in Baltimore and starred Sissy Spacek and Kevin Kline. That would have provided a substantial payday, but Hoffman does not compose film music, he says, and fears that if he had done it even once, he would never have been able to come back to serious composing. He tells the story with no apparent regret. Meanwhile, he keeps turning out new compositions. He likes a just-completed solo guitar piece, and is working on a string trio. "The middle may be the most beautiful thing I've ever written. But the outer movements are like watchdogs keeping people away from the middle. People will probably get so turned off they'll never get to the middle movement."

He ekes out a living teaching private guitar lessons two days a week in his apartment. In a rare move to improve his finances, he recently applied for two grants. He knows he did not get one and says he does not expect to get the other. No matter. His friend John Locke observes, with what he calls "reserved concern" tinged with admiration, "Larry will work for eight cents an hour. He doesn't care about that."

All he cares about is the daily work of composing. "I'm doing now what I've always wanted to do," Hoffman says. "This is my last stop. I am a composer."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged classical music, peabody, blues, contemporary composers