While typical school community events may be centered around a bake sale or potluck, at a recent open house at the Digital Harbor Foundation afterschool program, store-bought cookies sat mostly untouched. Families and their children were gathered at the foundation's Tech Center in South Baltimore to build lighted snowflake ornaments using working circuits. Many of the program's teenage participants lined the outside of the room showing visitors—including, on this night, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake—their dexterity with 3-D printers, computer programming, and various gadgets.

On first glance, the kind of hands-on learning environment favored by the Digital Harbor Foundation may look like a modern shop class. But behind the tools and technology is an emerging approach to how and what students learn that is bubbling up inside and outside the nation's classrooms.

As technology makes information abundantly available and disrupts long-established industries, educators are rethinking what is necessary for kids to learn and how that relates to what students "know." What do we teach students when information is ubiquitous and ever changing? What happens when students can learn as much on their own as they can in the school building? The answer to those questions has a profound impact on the role of the future teacher.

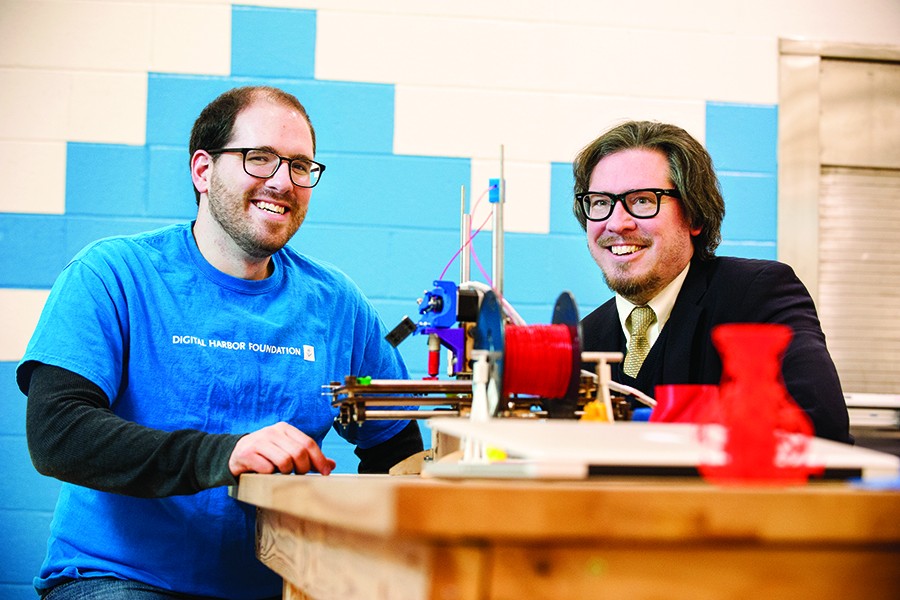

Both Shelly Blake-Plock, Ed '05 (MS), who trains the teachers of tomorrow as a faculty associate at the School of Education, and his former student Andrew Coy, Ed '11 (MAT), the executive director of the Digital Harbor Foundation, believe great teachers are more important than ever. But, they say, the most successful teachers will not be those with the most subject expertise, but rather those who are continuously learning on their own. Before Coy welcomed his amateur engineers for the night, he and Blake-Plock sat down to discuss the future of education.

Shelly We hear a lot about how the teacher is no longer the content knowledge manager. To a certain extent, that's always been true, especially in K-12. For example, it's relatively rare for a K-12 English teacher to be an active working poet or author. One of the things I'm interested in is how that separation can break down. There's an opportunity now, especially through social media, for teachers to be active participants in fields that they previously were only in a position to talk about. Teachers now can become, with their students, much more active and engaged participants in a culture that spreads far beyond the classroom walls.

Andrew And this is where the history of education comes in. One hundred years ago, in many ways the classroom was meant to be isolated from the real world. Factories were dangerous, exploitative places—the idea was to keep kids away from the world of work, as a civic responsibility. In today's world, however, if you're disconnected from that real world, you are borderline obsolete. And that's the problem that teachers and students alike are facing: how to be connected with what's going on around you in a more real-time way.

S It's something you see in the very best art teachers, for instance. Artists practice their craft, they experiment with their technique on their own, and they bring new things into the class. Just bringing that awareness, that sense of not being afraid to try new things, to make decisions about what works and what doesn't work—I think we've seen that from the best creative teachers for a long time. With the technology paradigm shifting where it is, we are going to increasingly see the influence of a creative, interactive approach across the board.

One of the most interesting things I've seen is the development of EdCamp, an informal professional network founded by a few teachers in Philadelphia and now operating globally, online and in-person. I think the next step is educators actually creating the new technologies, the new systems. I look to things like EduClipper, an online platform for teachers to share lessons; the training resources for connected educators that Will Richardson and Sheryl Nussbaum-Beach have put together through the Powerful Learning Practice network; or to the organizers of #EdChat, a Twitter chat that connects teachers from around the world. I think that is a hint of where things are going—to a place where the profession is more open and transparent and where things are actually being built by practitioners.

A One of the key traits for a teacher now is a lack of fear of the unknown. Teachers for so long have been told, "You are the expert." And if they don't feel like they are the expert on something, they don't want to talk about it. We want to break down that fear and say, "No, you are an expert— in learning. If a student sees you actively learning, you are communicating to them a valuable lesson."

The kids are working on their own projects; they don't need someone standing nearby with a special action for them. They take ownership of the project. For teachers, it takes a willingness to be uncomfortable or have a degree of uncertainty at the beginning.

S People actually expect creativity in learning now. They expect commentary in real-time. They expect a conversation as opposed to a speech.

A I remember back when people were talking about computers and the Internet, they were afraid it was going to isolate people from each other; they were going to not be tuned into their world around them. Now, through social media, finding like-minded and similarly passionate educators out there is really empowering. It says, "Go out there and don't be afraid of learning."

Posted in Science+Technology