In the New Testament's Gospel of John, chapter 20, verse 17, when Christ comes upon Mary Magdalene after he rises from his tomb, he says, "Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended/ to my Father" (King James Version). The Latin translation is noli me tangere, a phrase that became a trope in religious artworks that celebrate the life of Christ: the robed Jesus standing with a hand raised in beatific denial of Mary's longing as she stands close by, hands reaching toward him but never coming into contact with his flesh.

Image credit: PHotograPH courtesy of DOM UND DiözesaNMUseUM

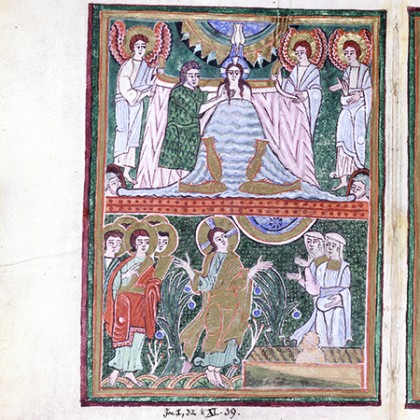

And yet in an illustrated manuscript dating from the early 11th century that was commissioned by the Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim in the Holy Roman Empire, Mar y touches Christ's foot in the noli me tangere scene. It's an utter violation of the gospel's command. "This image is one of the few that has been studied [and it is] extremely unusual because this scene by definition is about not touching," says Jennifer P. Kingsley, A&S '07 (PhD), the assistant director of Johns Hopkins' interdisciplinary Program in Museums and Society. "And in fact, she is touching him. So why is that?"

Kingsley explores that question in her debut book, The Bernward Gospels: Art, Memory, and the Episcopate in Medieval Germany (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014). The book is a considerable expansion of the research she conducted for her dissertation, which focused on Bernward as an arts patron. He was the 13th bishop of Hildesheim, which today is a city of nearly 100,000 people in central Germany. He came from a noble family, was educated at cathedral schools (the prototypes of medieval universities), tutored the future Emperor Otto III, and traveled. When Bernward became bishop in 993, Hildesheim was a powerful hub in the Holy Roman Empire, and he wanted to honor that stature. He founded the Benedictine Monks of Saint Michael's Abbey and started construction on the Church of Saint Michael's, today a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site. The church, which wasn't completed until after his death in 1022, has a column sculpture depicting 28 scenes from Christ's life and bronze doors that are considered medieval masterpieces and frequently included in art history surveys.

Less studied are the images in this codex, which Bernward presented to the monastery in 1015 as a commemorative object. Kingsley says the illuminations are "quite extraordinary," their gold still sparkling and their colors vivid. Previous research was chiefly historical, identifying Anglo-Saxon English and Roman influences in their iconography and imagery. The images themselves had never been interpreted as a visual set. "That is really what drew my interest," Kingsley says. "The deeper I looked into the images, the more I noticed. And after looking for seven years, I noticed how many paintings in the work showed figures touching Christ." She points to another illumination, of John baptizing Jesus. "He's basically manhandling Christ," she says, pointing out that John has hands on each of Christ's shoulders. In typical medieval baptism scenes the two are close, perhaps with a hand held above Christ's head, but not so intimate. Kingsley explains that there is no parallel for this iconography in medieval art. "All of these little details increasingly drew my attention. I wanted to understand what they might have meant for their patron and audiences." She turned to encyclopedic sources and scientific treatises about touch and philosophical discussions of the senses that may have influenced Bernward's ideas.

Sacred art typically appealed to vision to inspire worship: Christ as a ray of light illuminating man, the divine spirit. In Bernward, Kingsley argues that the bishop presents both sight and touch as a way to consider the self in relation to the divine. Both could be avenues through which to seek spiritual enlightenment. In the Middle Ages, "if you think about a world in which when you go to the church—and you're not going all that often if you're a layperson—it's a very impressive experience," Kingsley says. Medieval art served theologians' arguments about how images could appropriately direct the mind to God. "I argue that in this case the bishop is trying to create a dual sensory approach, one through sight, which has been quite well studied, and one through touch, which has not really been studied well by art historians."

But still, seven years of looking? Kingsley laughs. "I remember that being one of the things people told me when I started my dissertation work: Make sure you choose a topic that can sustain your interest over time because you will be living with it for a while." She found that in the Bernward Gospels. "It's so dense and so complex, not only visually because of the densely layered ornament but also in terms of its subject matter. That was the most gratifying aspect of the project because that is to me what distinguishes art history as a discipline: the process of looking in a sustained way and over a long time, at something, each time noticing new things."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged program in museums and society, religion, medieval germany, christianity, theology