We are set to meet on Monday morning, Daniel Menaker and I, and he suggests that I come to his apartment, because the coffee is better there than at the place down the street. But Menaker, A&S '65 (MA), disclaims any pretensions of connoisseurship soon after I arrive. "I'm not a foodie—I'm waging a nano-war against kale," he says, marveling at the obsessiveness given to ingredients these days. About coffee: "I always said, give me whatever nasty potion was available. But now it's like all Upper West Side things—slightly gourmet. To me, it seems like a strange life."

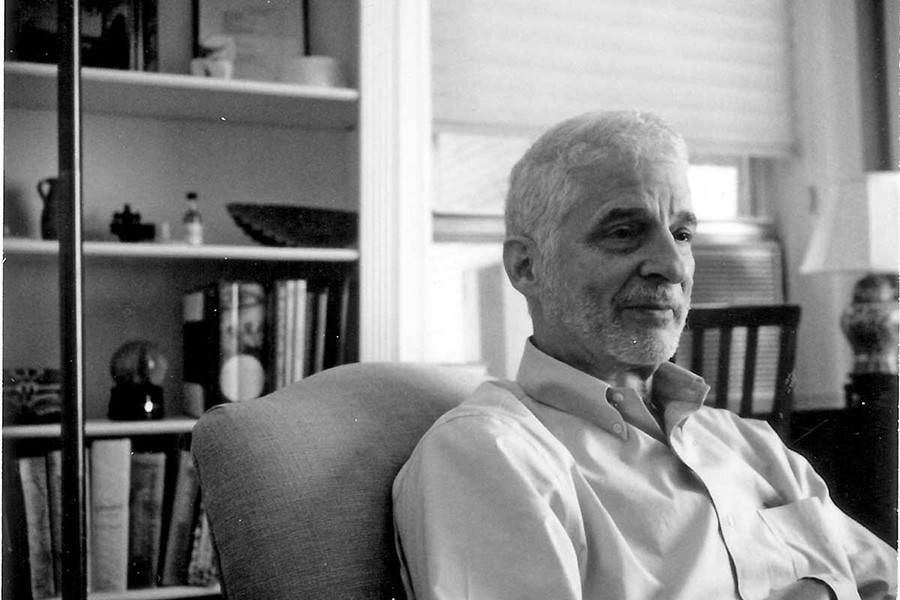

A strange life, maybe, but also a pretty good one, even with a few tragic moments, and it's recounted in My Mistake (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013). Menaker's memoir captures a pair of lost worlds: the old lefty Greenwich Village, where he grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, and the byzantine kingdom of The New Yorker, where he worked for 26 years, mostly during the peculiar editorship of William Shawn. Although the book paints its author as a slightly aloof figure, armoring himself with ironic detachment, Menaker is friendly and easy to talk to. One of his five earlier books is about the art of conversation, so I guess I shouldn't be surprised.

Between those two stretches of Menaker's life, downtown and uptown, there was his time as a graduate student at Johns Hopkins, which he recalls with respect if not exactly pleasure. He'd learned to read poetry, he says, in his undergraduate years at Swarthmore. "But Earl Wasserman"—who taught at Hopkins from 1948 to 1973—"was fabulous, and mean, and impatient . . . and taught me again. That's made a difference in my life." There was also the less impressive American literature specialist Charles Anderson, who was "a wonderful teacher but required you to buy the books he'd written, which was so venal!"

More coffee? More coffee, please. It really is pretty good.

So it was back to New York, where, in 1969, he landed at The New Yorker, working first as a fact checker, then a copy editor. William Shawn was never exactly a fan: When Menaker had been at the magazine perhaps five years, a top editor pulled him aside to say, "We're not going to make you leave, but we do want you to find another job." He tried to do so, but nothing panned out, and Menaker soon found a mentor in William Maxwell, the magazine's fiction editor, who helped ease him out of purgatory, publishing his short stories and helping with the interoffice politics. Throughout the book, "my mistake" is a recurring meme, almost a punctuation mark, as he recounts various moments of iffy judgment, ill-conceived social interactions, and bad career moves. Those mistakes gradually became less frequent, and Menaker ultimately stayed at the magazine for 26 years, editing the likes of Alice Munro (very happily) and Pauline Kael (less so). In 1995, he moved on to the book world as executive editor-in-chief at Random House, and, apart from a brief interregnum during which he went over to HarperCollins, he stayed till 2007.

More coffee? Sure. Plus some off-the-record publishing gossip.

The book recounts what a lot of publishing people would consider a golden career, but Menaker's was not a life led effortlessly. Along the way there were panic attacks and episodes of despair. Underneath it all lay pernicious guilt over the death of his brother, which occurred after an injury that Menaker had, indirectly and inadvertently, helped cause. (Psychoanalysis helped a lot, he says, though he stopped therapy many years ago, once self-examination became "a habit of mind.") And then, a few years ago, came an especially nasty surprise: A lung cancer diagnosis led to surgery and chemotherapy and, eventually and fortunately, remission. "Everything is different," he says, about what the experience changed in him.

Yet some of that old stuff from the academy did actually linger as he managed his illness. "I wish everyone had to concentrate on poetry as much as I did," he says, adding that it was "against my will at first. I was a semi-athlete, and I was always eschewing academic pride. It doesn't save lives, but it does give your life a richer context. And I wouldn't be talking about this if it weren't for the cancer diagnosis, which is of course in some ways awful and frightening, but also renewed my interest in bigger answers, questions of faith. Poetry is a real solace." Much more than kale. Or coffee. We finish, and I head to the office to write, buzzing.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged daniel menaker, the new yorker, my mistake