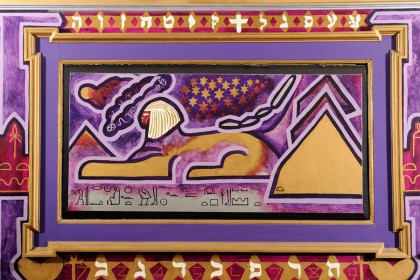

"I can't go to The Apocalypse and feel good now," says artist and author Bob Hieronimus, who painted the room-filling mural on the second floor of Homewood campus's Levering Hall. Almost 45 years later, he is hoping to restore the painting, which, he says, does not depict the end of the world as told in the Bible. "The mural is about how history is cyclical and how what determines the cycles is the key." The detail above depicts the separation of the sexes into male and female.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

In 1968 then Johns Hopkins Chaplain Chester Wickwire asked Hieronimus, a Baltimore artist, if he would paint a mural on a second-floor wall of Levering Hall, a room known as Chester's Place that served as a coffee-shop gathering spot and music venue for students. Hieronimus' work brought together visual art and the science of symbols. Flowers, hearts, serpents, five-pointed stars—these had ancient meanings for him, and he used them to talk about what he observed happening in the world around him. His artwork earned him a number of fans in the rising anti-war and rock 'n' roll countercultures, and he ended up chatting with a few nascent stars of the era, including Jimi Hendrix. That summer, Hieronimus basically moved into Levering, staying there while he painted the mural, called The Apocalypse. He was paid $1,000.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"I warned [Wickwire], 'You're going to catch holy hell for this,'" says Hieronimus, now a noted historian, author, and radio host of 21st Century Radio. "And he said, 'Bob, I know what you're doing and I know why you're doing it. I will not interfere with anything you do. Don't worry. This is Johns Hopkins, and we're open to anyone's ideas.'"

Hieronimus worked in Levering for six months, finishing in February 1969. It wasn't that he worked slowly. What was going on in his head just wasn't going to fit on one wall. "I kept getting all of these ideas and there wasn't enough space, and after about the second or so month I'm looking around and there's all these empty walls," Hieronimus says. He asked Wickwire if he could make the one-wall mural bigger. "He said, 'Do what you want. Paint the whole thing.'" Hieronimus filled the entire second floor and its stairwell with his symbol-dense vision.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Symbols are the forms humans have used to communicate meaning since before written language, says Hieronimus. And cultures have throughout history used them to interpret and represent both the rational and the mystical. Hieronimus, who earned his PhD from Saybrook University, studied everything from mythologist Joseph Campbell to Carl Jung, Rollo May, Abraham Maslow, and British philosopher Herbert Read. And he was in touch with various Johns Hopkins faculty, including esteemed archaeologist William Albright. So Hieronimus was serious about his studies—he just gave equal weight to the rational and the mystical.

"That at first was a bone of contention with the Egyptologists at Hopkins," Hieronimus says, describing his use of Ra and Om (at right) on one part of the mural. Several Egyptologists commented on his representations of certain headpieces. "They'd say, 'I've never seen loops on these.' I said, 'I know to you this looks to be Egyptian, but that part of it is not Egyptian. That is taken from research dealing with Atlantis.' And no archaeologist at Hopkins was going to say, 'Oh, Atlantis? OK.' It was more, 'You've got to be crazy.'"

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Hieronimus' use of Ra and Om comes from an organizational idea that runs throughout the mural. "On the stairway as you go up [to the second floor], there's a big wall that's always puzzled a lot of people because when they look at it they see what was referred to in esotericism as a bisexual being," he says. "At a certain time in our development we were both male and female. And that separation of the sexes was important because at that point the intellect, which is associated with the masculine, started to be developed with regard to intuition and the feminine side. So those two, the Ra and Om, the sun and the moon, were all related to the male-female, which is followed throughout the entire mural. On every one of the painted pillars, you will always see silver on one side, gold on the other, purple on one side, red on the other, because they were related to color symbolism and the male-femaleness of things."

In the lower left corner of the Ra and Om wall is a female face wearing a gold headpiece with what appears to be pink flames shooting from her eyes. "The fire coming out of the eyes, that was about Jesus," Hieronimus says. "Not Jesus Christ as a person but the cosmic christ, or Christos, which is a higher form of consciousness, which is totally lost today with fundamentalism, because to them Jesus Christ is god. He's not a higher consciousness, he's god. I don't want to hurt your feelings, but I don't believe that. I don't think he was god. Like us, he had an element within him that he had to raise over the decades in his life to become a higher cosmic consciousness, as [occult scholar] Raymond Buckland and the others would refer to it. So that fire in the eye has to do with psychic and spiritual vision rather than just physical vision."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Hieronimus refers to such higher consciousness in one corner of the mural, where he paints "He is coming" in blue letters beneath red flames. "That I would like to change some time," Hieronimus says of the graffito. "It shouldn't have been he. It can't be she. How I corrected that on the Woodstock bus was having SheHe. It's the being he and she—higher consciousness. It's not male, it's not female, it's a balance. And I put it around fire and a lion coming up, and the leonine, again, puts too much emphasis on the male aspect of it. There wasn't enough of the feminine."

Hieronimus says students would often swing by and check out what he was up to, and one became a great mentor. "My first spiritual leader was a student who was doing his doctorate at Johns Hopkins, Narayan Joshi," Hieronimus says. "He actually was the best man at my wedding. He was Hindu, and he taught me all about the philosophy of the Hindu tradition. They have some of the oldest traditions on the planet, older than Egypt's and more profound. The Sanskrit language has always fascinated me, and there's a language called Senzar—that was my greatest fascination because this supposedly was the first symbolic language of humans on this planet, but there's very little information on it. It's a very ancient language upon which Sanskrit was based.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"What I learned from him also was, you've got to diminish the ego," he continues. "The ego is a problem. When he came up, he said, 'You're working on your inner self, right?' I said, 'Yeah.' And he said, 'Let me teach you about certain meditations.' We had a wonderful relationship."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

These days, the second floor of Levering Hall houses the Tutorial Project, and the space has seen some wear and tear. Hieronimus would like one day to raise money or obtain a grant to restore it to better conditions. "It hurts—not because of all the posters and things like that they put up on the wall," he says. "I understand that this is a place for them to do what they need to get done. I'd love to see it in pristine condition again and to be able to interpret it in a way so that people understand this is not the end of the world, this is not from the Bible. This is about how history is cyclical. It comes and goes, and what determines the cycles is the key."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged visual art, painting