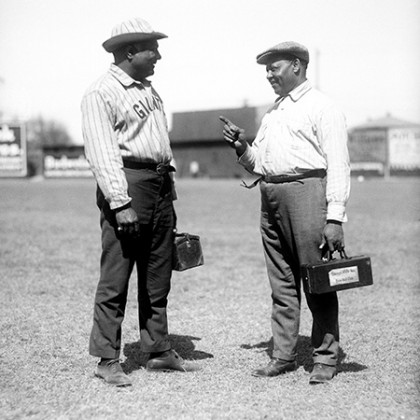

Third baseman John Joseph McGraw was 5 feet and maybe 7 inches of never-back-down. He was 17 when he became a Baltimore Oriole in 1892, joining a team of pugnacious gents that dominated the 1890s. When he became player-manager of the New York Giants in 1902, he had a reputation for winning at all costs and, soon, a nickname: Little Napoleon. Giants player-coach Arlie Latham once said McGraw "eats gunpowder every morning and washes it down with warm blood." Touchy-feely just wasn't in McGraw's playbook. And yet, in June 1922, when McGraw stood at a podium inside a funeral parlor on Manhattan's East 72nd Street to eulogize the Giants' African-American trainer Ed Mackall, the national edition of the Chicago Defender reported that the Little Napoleon "brought tears to the eyes of his players" and finally "broke down from emotion and cried like a child at the end of his talk."

Image credit: Bettmann/Corbis

Baseball's collective memory is long, but Mackall's story remains unfamiliar. Most of what's known about him fits into a 166-word anecdote about a trophy bearing his name that appears in Inside the Baseball Hall of Fame, a book published in April by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. "I don't think prior to this book coming out that many people knew either that we had that trophy or who Ed Mackall was," says Tim Wiles, the director of research at the Hall of Fame who researched Mackall and wrote the short piece in the book. Wiles says he hadn't known about Mackall prior to looking into him for the book. "What I found was a pretty compelling story about an African-American person being involved with major league baseball at a time when we don't think of African-American people being involved and when social equality in the United States was still a pretty distant dream, both within baseball and society in general."

Born in Baltimore in 1876, Mackall became the trainer—at the time, "rub-down man" or "rubber"—for McGraw in 1899, when McGraw was player-manager of the Orioles. McGraw later brought him to the Giants, where Mackall spent the rest of his career before his untimely passing at 46 or 47 in 1922. Prior to major league baseball, Mackall was a trainer at Johns Hopkins University from 1890 to 1899. At least, that appears to be the situation. University employment records don't go back that far. But a few newspaper articles from the time refer to his duties as a trainer at Hopkins.

Searching newspaper archives turns up about two dozen stories mentioning Mackall; some are reprints of appreciation obituaries, most mere mentions that simply identify him as the Giants trainer. These fill in his biographical plot points: At the time of his death, he lived with his wife, Nellie, at 64 Kosciuszko Street in Brooklyn. He had a son, name unknown. He was a member of the Hiram Lodge No. 4 F. & A.M. masonic lodge. His favorite hymn was "Abide With Me," which was sung at his funeral. His body was returned to Baltimore and buried next to his mother. Attending his services were several past and present members of the Giants organization and the entire Bacharach Giants team, the Negro National League club based in Atlantic City. He was once a boxing trainer. He was known as "Eddie" and "was one of the most popular attachés of the club and was well liked by every one," according to a story in the New York Age.

Mackall was so associated with the big-league Giants that in the April 2, 1938, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, Chester L. Washington dedicated his column to sports trainers, the "men behind the stars," and noted that Mackall "made the New York Giants one of the best physically conditioned clubs in the diamond world." Indeed: With the Giants, he maintained the arms of famed pitchers Christy Mathewson and "Iron Man" Joe McGinnity, and the club won National League pennants in 1904, 1905, 1911, 1912, 1913, 1917, and 1921 and the World Series in 1921.

Washington went on to say that Mackall was one of a cadre of esteemed black trainers in the league: Kirby Samuels of the St. Louis Cardinals, George Asten and Ed LaForce with the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the legendary William "Bill" Buckner of the Chicago White Sox. What's left unstated is that African-Americans were accepted in the clubhouse but not on the fields. One newspaper story notes that in the summer of 1919, Mackall hid under a passenger train's seats when the Giants passed through Springfield, Illinois, the site of a race riot earlier in the year; another reports that McGraw felt it prudent to send Mackall back to New York rather than have him accompany the team to Chicago, where race riots had broken out as well. And a short piece in the October 2, 1908, Salt Lake Telegram points out that one member of the Giants isn't entitled to a share of postseason money should the club make the series: "The unfortunate person is Ed Mackall, colored trainer of the club."

Which is simply to acknowledge that while Mackall seemed respected and liked by the Giants organization, he was still subject to the racism that came with being a black man in America. The New York Sun sports writer Frank Graham wrote that the Giants considered Mackall not only a trainer "but guide, philosopher and friend" in the same paragraph that he calls Mackall a "wizard at handling the club's baggage" and praises him via Rudyard Kipling: "Like Gunga Din, he was 'white, clean white, inside.'"

Mackall is never quoted in the articles in which he's featured, forever in the margins of his own life's story. One person, at least, saw what he brought to the team. When the Giants won the pennant in 1911, every member of the team got a trophy—save Mackall. So McGraw took his and had it engraved with Mackall's name and presented it to his trainer. At least, so suspect researchers at the Hall of Fame, where the trophy resides. "We know that the trophy was awarded to every player and to the manager on the team," Wiles says, who notes Mackall's trophy was donated to the museum in 1965. "Our theory is that McGraw took his own trophy and had it reinscribed and presented it to Ed Mackall. We don't have any evidence of that, but it's an educated guess on our part."

Posted in Athletics

Tagged history, baseball, ed mackall