The September 2012 conference of the International Congress of Coptic Studies in Rome threw a wrench into 2,000 years of Christian thinking about women's role in the early church. There, Harvard University divinity Professor Karen L. King announced the existence of a piece of papyrus, made available to her by an anonymous collector, that she estimated to date from about the fourth century A.D. It is a 1.6-by-3.2-inch rectangle and contains eight fragments of text written in Coptic. One line in particular translates to "Jesus said to them, 'My wife.'" The line beneath that reads, "She will be able to be my disciple."

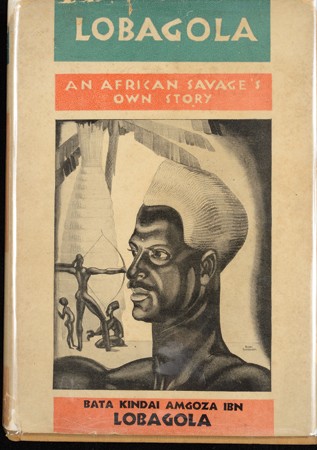

Image caption: ‘LoBagola: An African Savage’s Own Story’ (A. A. Knopf, 1930) was written by Baltimore forger and imposter Joseph Howard Lee, who claimed to be born in the African wilderness, and to be a direct descendant of the Jewish diaspora following the destruction of the ancient Temple of Jerusalem. The book is part of the ‘Bibliotheca Fictiva’ collection of the Sheridan Libraries.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

This revelation appeared just as Johns Hopkins' Walter Stephens, the Charles S. Singleton Professor of Italian Studies in the Krieger School's Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures, and Earle Havens, the William Kurrelmeyer Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts in the Sheridan Libraries, were teaching a graduate seminar titled Literature and Truth: Forgery and Theory from the Renaissance to the Present. In addition to addressing King's Jesus revelation, the students were able to conduct primary research in the Arthur and Janet Freeman Biblioteca Fictiva collection of literary and historical forgeries—comprising complete or partial texts that make fictitious historical claims, or were otherwise created and falsely attributed to famous figures—that the Sheridan Libraries had recently acquired.

With more than 1,500 rare books and manuscripts, it is the premier collection of its kind, containing well-maintained examples of forgeries dating from antiquity to the 20th century and their surrounding scholarship. The students were learning the skills necessary to properly interrogate fraudulent or questionable documents, including the "Gospel of Jesus' Wife," as the aforementioned Coptic fragment has come to be known.

"We immediately found 10 things that make us very doubtful that it is authentic," Havens says. For one, the fragment is almost perfectly polygonal, not the irregular shape of something surviving many centuries, as papyrological fragments often are. "I've never seen a fragment of papyrus this uniform in size," he says, adding that "the paleography appears atypical for this period, using a brush instead of a stylus or reed pen."

Stephens points out that the text on the fragment conveniently contains Jesus addressing his wife. "This is pure Da Vinci Code stuff," he says, alluding to Dan Brown's best-selling historical fantasy.

"A significant proportion of literary and historical forgeries tell us things that sound attractive," Havens says, "filling in gaps that leave much of the past obscured by time."

Havens and Stephens are sitting in one of the Special Collections' seminar rooms in the Brody Learning Commons, along with Neil Weijer, a doctoral candidate in the Department of History who took their seminar. Weijer's research explores a time in English history, beginning in the 1400s, when England's historians believed the country was founded by a great-grandson of Aeneas, a hero from the Trojan War. Weijer recognizes the aspirational misinformation that forgers exploit when writing fake histories, offering some tidbit of ancient "fact" to conform to what people want to believe in their present moment. The more ancient a document, the more authoritative and credible it seemed to be.

"Give them what they want but nothing more," he says.

The three scholars have gathered to discuss the exhibition Fakes, Lies, and Forgeries: Rare Books and Manuscripts from the Arthur and Janet Freeman Bibliotheca Fictiva Collection, which opens Oct. 5 at the university's George Peabody Library in Mount Vernon. The exhibition was curated by Havens, Stephens, and three students from the seminar: Weijer; Janet Gomez, of German and Romance Languages and Literatures; and John Hoffmann, of the Department of English. Each was responsible for a section of the exhibition and contributed an essay to its catalog, the first treatment of the collection since its arrival at Hopkins.

It's tricky getting them to discuss the exhibition in broad terms, however: They're like baseball fans who can turn an obscure statistic into a riveting digression. In their case, it's history's frauds that get the story rolling, and these histories can put any sports tale to shame.

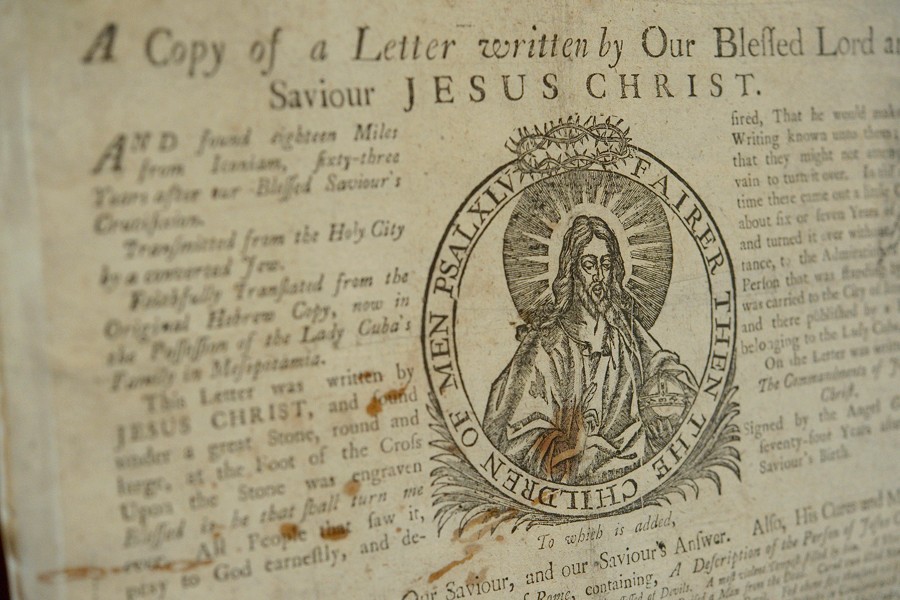

The notion of Jesus as a man with long hair and lightly colored eyes? That derives from a forged medieval letter ostensibly written by a nonexistent Publius Luntulus to the Roman Senate providing an eyewitness account of Jesus' appearance.

"The Bible never tells you what Jesus looked like in life," Havens says. "But if he's the savior in a highly iconophilic religious tradition like Roman Catholicism, you want to know what he looked like. Hence this 'eyewitness account' indicating that Jesus had brown curly hair down his head with gray eyes—that's where we get the image of Jesus that we know today, largely from a forgery."

This is how forgeries work: There's a gap in knowledge that gets filled by an opportunist armed with enough information to make an invented story plausible. "Forgeries nearly always tell someone what they want to hear," Stephens says, adding that when people want to believe that an assumption is a fact, "they often need a document saying so."

The Stephens-curated portion of Fakes examines the 15th-century forger Annius of Viterbo, a figure Stephens has researched since first coming across him in the mid-1970s. Annius upended European history for more than 200 years by inventing a history in which the Etruscans emerge, as Stephens says, as "the fountain of all knowledge, wisdom, and cultural achievement of antiquity in the world."

"Annius creates this completely fictitious ancient history and turns the whole of ancient history on its head," he says. Annius' work was dismantled in the late 16th century, but in the intervening years his fraudulent ideas were frequently cited and repeated, and informed other histories.

It's those ripples that cascade out from forgeries that make the study of them today so rewarding. They offer a glimpse into how stories become history and how the past shapes the present, and reveal recognizably fallible human motivations behind forgers' intent. People forged for both material and political gain, out of a sense of the need to "document" that a country or people descended from heroic forebears, or to justify a sense of patriotism through "proof" that such is how it has always been.

After all, it's hard to argue with the past. "One of the reasons historical writing is very successful is because there are things professed in the past that transcend human understanding, but people still want to understand them," Weijer says. "And as long as there are incomplete explanations, people are going to try to fill in what they don't know. A lot of the reasons these forgeries work, and why some were so successful for so long, is that they gave people—not just one person, but a lot of people—what they were looking to believe anyway."

It's important to recognize that throughout history, forgeries were not collected and kept together in a special collection such as the Bibiotheca Fictiva at Johns Hopkins. They have long appeared rather randomly on the shelves of libraries in universities, monasteries, and private homes. And over the centuries, the forgeries in the Biblioteca Fictiva were proved false, not by academics interested in any one specialized research collection but by scholars doing their jobs at various points throughout history.

Studying forgeries "requires a kind of forensic imagination that we should probably be engaging in when we look at any text," Havens says. "People can be so uncritical of texts, particularly in the age of the Internet, that perhaps they need to be reminded, now more than ever, that they're in danger of being duped. At the end of our graduate seminar, one student seemed really crestfallen, complaining, 'I can't believe anything anymore.'" Havens' response was automatic: "Well, now you know what it's like to be a scholar."

That's what's so engrossing about falling down rabbit holes with Havens, Stephens, and Weijer when they talk about the exhibition. In 2014 it's easy to laugh at the claims proposed by some of the forgeries, which sound as ludicrous as stories in the tabloids, but the closer disputed ideas are to the present moment, the more contested the discussion of known "facts" can become. What the Founding Fathers of this country actually meant in their documents, for example, is a source of continual and heated legal and political debate for everyone, from broadcast pundits to the Supreme Court.

Even the authenticity of the "Gospel of Jesus' Wife" remains in dispute, and Harvard maintains a website devoted to its study. And Fakes, Lies, and Forgeries offers a scholarly exploration of how the past is not fixed so much as it is suspended in a perpetual state of flux by people with the power to shape it. "We haven't found everything that there is to know, and forgers really exploit those gaps to their advantage," Weijer observes. "So now, more than ever, history's not just open for debate; it's open for renewal."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged rare books, sheridan libraries