The Johns Hopkins University's Sheridan Libraries, in partnership with University College London's Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, or CELL, and the Princeton University Library, have been awarded a $488,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to implement The Archaeology of Reading in Early Modern Europe. This digital humanities research initiative will explore historical reading practices through the lens of manuscript annotations preserved in early printed books.

The principal investigator for this project is Earle Havens, the William Kurrelmeyer Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Sheridan Libraries, who will be working closely with two of the world's leading scholars of the history of reading: co-principal investigators Lisa Jardine, a professor and director of CELL at University College London, and Anthony Grafton, a professor of history at Princeton.

"We are extremely grateful to the Mellon Foundation for its support of research into this fascinating but underexplored part of history," says Winston Tabb, Sheridan Dean of University Libraries and Museums at Johns Hopkins. "Renaissance readers left us a wealth of material to investigate. This kind of deep discovery work would not be possible without the combined expertise of an international team of humanists and technologists bringing a broad range of expertise together, and we look forward to sharing what they uncover with the world."

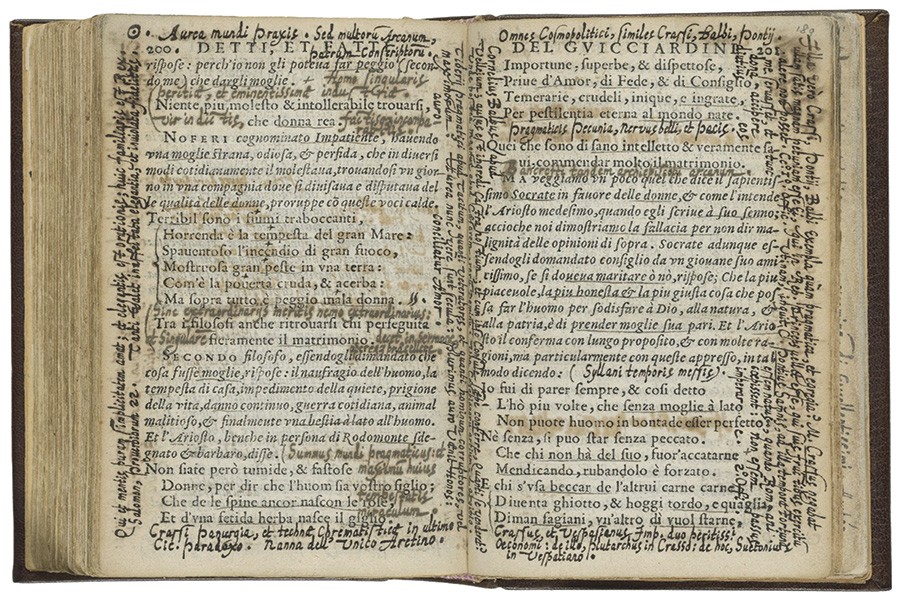

The project builds upon several decades of humanistic research that has focused on the printing revolution of the 16th century, and the widespread practice by active readers of leaving often dense, interpretive manuscript annotations in the margins, and between the lines, of the books they read. This diverse evidence of annotation provides a considerable range of unique and largely untapped research materials, which reveal that readers—much like users of the Internet today—adapted quickly to the technology of print: interacting intimately, dynamically, socially, and even virtually with texts.

The revealing intimacy of these research materials is palpable, Grafton says. "Reading these marginal notes gives us the chance to stand by the desks of Renaissance scholars and look over their shoulders while they work at their trade. We can watch them read and respond to a vast range of books, tracing their thoughts and glimpsing the ways in which they used their scholarship to advise kings, ambassadors, and archbishops."

This body of primary source material is among the largest, least accessible, and most underutilized of original manuscript sources from the early modern period, owing to the fact that they are almost entirely uncataloged, or undercataloged, by major research collections.

"There are so many parallels between our project and the digital world of information that we live in today," Havens says. "These notes reveal a largely unvarnished history of personal reading within the early modern historical moment. They also embody an active tradition of physically mapping and personalizing knowledge upon the printed page. The added practice of referencing and cross-referencing other works in these marginal annotations also allows us, like those early readers, to engage with the presence of 'virtual libraries' within the space of a single book."

The history of reading remains a rich area for research, as scholars seek to better understand these reading habits and strategies, though it has remained a particularly daunting task when conducted in a purely analog context, particularly with books that contain literally thousands of notes.

"This is an exciting moment," Jardine says. "We have been aware for some time of the unique importance of the copious annotations to be found in early modern books—marginal notes in ancient and modern languages tagged to printed passages, and cross-referenced to other notes and other books—but documenting and sharing them has largely defeated scholars. Only now, with resources being developed within the digital humanities, will we at last be able to do so."

By treating marginal annotations as large sets of data that can be mined and analyzed systematically in an electronic environment, the project team will create a corpus of important and representative annotated texts with searchable transcriptions and translations in order to begin to compare and fully analyze early modern reading by a number of dedicated Renaissance readers and annotators.

Over the next several years, the Archaeology of Reading team will integrate the digital humanities expertise of both CELL and the Sheridan Libraries' Digital Research and Curation Center, as well as the collections of the Princeton University Library and other major repositories in the United States and Europe. The initial phase of the project will focus on the transcription and translation of a select number of heavily annotated books, and the allied adaptation of the open-access Shared Canvas viewer to maximize user interaction with these complex, composite early modern texts through a publicly available website.