100 years ago, most psychiatric patients were sent to asylums, more for isolation than treatment and often in deplorable conditions. The field of psychiatry was young and naive.

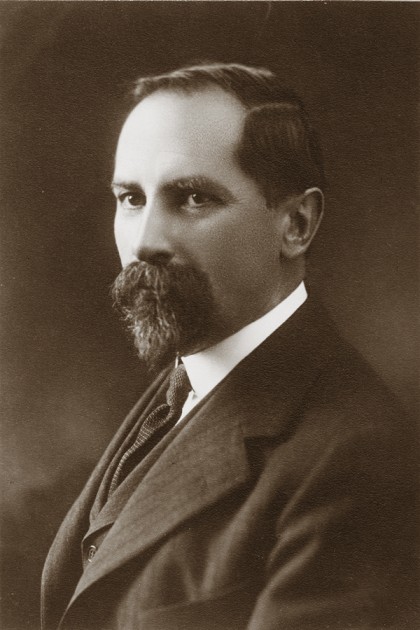

Image caption: Adolf Meyer, first director of the Phipps Clinic

Image credit: THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

It was against this backdrop that the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins was completed in 1913, helping usher in a new era of psychiatric care in a setting of teaching and scientific research. It was a prestigious institution from the outset, and its reputation endures a century later.

What made this academic psychiatry department exceptional? And how, after 100 years, does the department maintain its status in an ever-evolving world of medicine?

Perhaps the best place to start is with Adolf Meyer, the first director of the Phipps Clinic and the man who is credited by his successors for elevating psychiatry to a standing alongside general medicine.

"He produced a new, optimistic view about what the future held for psychiatry," says University Distinguished Service Professor Paul McHugh, who served as director of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the School of Medicine from 1975 to 2001. "It became more like medicine," he says, adding that Meyer understood that the discipline needed to move to the university setting to create a more rigorous and scientific environment.

Psychiatry wasn't academic at the time. Instead, McHugh says, "Patients were being removed from medicine and put into farms and left to vegetate. No one was learning anything more, or preventing more, or understanding."

Meyer, a neuropathologist, took a different approach, pioneering psychobiology, a term that sounds complicated but is quite simple, McHugh says. What Meyer meant was that we should be studying patients and their lives, not just their symptoms. Just as we are studying life at the molecular level, the study of life at the psychobiological level was a useful and necessary part of psychiatry.

Susan Lamb, who received her doctorate from the Institute of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins in 2010 and is writing a book on Meyer and the early years of the Phipps Clinic, says, "It boiled down to the mind and body and the relationship between the two. [Meyer] said there wasn't one. Mind was body and body was mind, and you couldn't separate them. You could take the heart out and study it, but it's not really a heart in any real sense of functioning after it's removed. He felt the same way about the mind and mental activity."

For Meyer, Lamb says, the dysfunction of the whole person had to become the focus of psychiatry. He called on clinicians to examine not only the bodies of patients but the circumstances in which mental disorder developed. He wanted detailed medical and life histories for every patient, applying the same scientific rigor happening in general medicine to the field of psychiatry.

Raymond DePaulo Jr., the Henry Phipps Professor of Psychiatry and current director of the department, says that Meyer wanted "a comprehensive psychiatry."

"He took an extensive and systematic history, and it had many elements," DePaulo says. "This holistic approach to psychiatry earned Meyer some criticism for being "profoundly vague," he notes, but Meyer felt strongly that when it came to psychiatric models for diagnosis and treatment, one size didn't fit all.

That comprehensive and systematic approach—one that endures today—allowed the department to resist falling prey to varying popular movements in psychiatry. Because it's a discipline with a strong emphasis on therapy, there's a risk of being vulnerable to these movements, McHugh says, such as diagnosing multiple personalities.

"We were very worried, and have been forever worried, that the tendency for a disciplined focus on therapy would get into fads," McHugh says. What set the Phipps Clinic apart, he says, is "across its history, we have been anti-fad."

Meyer's pragmatic point of view laid a foundation picked up by his successors, including behavioral psychologist Curt Richter and Ivan Pavlov-trained W. Horsley Gantt. John Whitehorn, Meyer's successor as director of the department, from 1941 to 1960, also continued that pragmatic thread with his elevation of social work as a therapeutic intervention, and through scientific work done under his leadership by Jerome Frank to identify the mechanisms that make psychotherapy work, explains Dean MacKinnon, an associate professor of psychiatry, who compiled and authored articles for the department's anniversary website.

In the early 1980s, the Johns Hopkins approach was further defined by four perspectives outlined in The Perspectives of Psychiatry by McHugh and Phillip Slavney. These four perspectives—disease, dimension, behavior, and life story—became a model of pragmatism for practicing psychiatry and the comprehensive approach that allows all Johns Hopkins clinicians to speak the same language, MacKinnon says.

Similarly, this comprehensive view of the whole patient has translated into a dedication to patient care, another enduring priority of the Phipps Clinic.

"In today's specialty-driven world of medicine, it might be seen as an anachronism," says DePaulo. "But our faculty, like Meyer, are committed to patient care as a strong and guiding mission imperative, including patients from near and far who have the most difficult-to-treat conditions." The clinic started with 88 beds—an unusually large number for an academic program, DePaulo says—and still has that number.

Today, clinicians at the Johns Hopkins department divide their time between research and patient care, both in a teaching setting. "Our students see patient care taking place in an academic setting, where successes, mistakes, and tricks of the trade are all on display," DePaulo notes. "It all comes together in one place, and that is on the ward where we are seeing the patients, we are doing research, and we are teaching medical students and residents and fellows. That's a commitment as much to students as to patients, to guide the next generation."

It's this next generation of leaders who will carry on the legacy of Meyer and the priorities set when the Phipps Clinic opened.

"The key is to pass it on, and the test is in passing it on. Do those people flourish themselves as great contributors to the discipline of the patient we are caring for?" McHugh says. "We are still producing the go-to psychiatrists."

But maintaining integrity can be difficult when the department also must just survive, MacKinnon notes. Other notable academic departments have struggled because of the changing financial landscape in medicine and academia. MacKinnon credits DePaulo with helping manage that shift, honoring the legacy and foundation on which the department was built while keeping a keen focus on the future.

For his part, DePaulo says he strives to set a tone for the department that values the mission of patient care. He recalls wondering, when he was younger and less experienced, what made the Phipps faculty so stable. "It's because we really feel like we are on a mission," he says. "The students sense that, and our residents sense that. We don't belong to any school [of thought]; it is the patient who is real."

Posted in Health, University News

Tagged psychology, psychiatry, adolf meyer