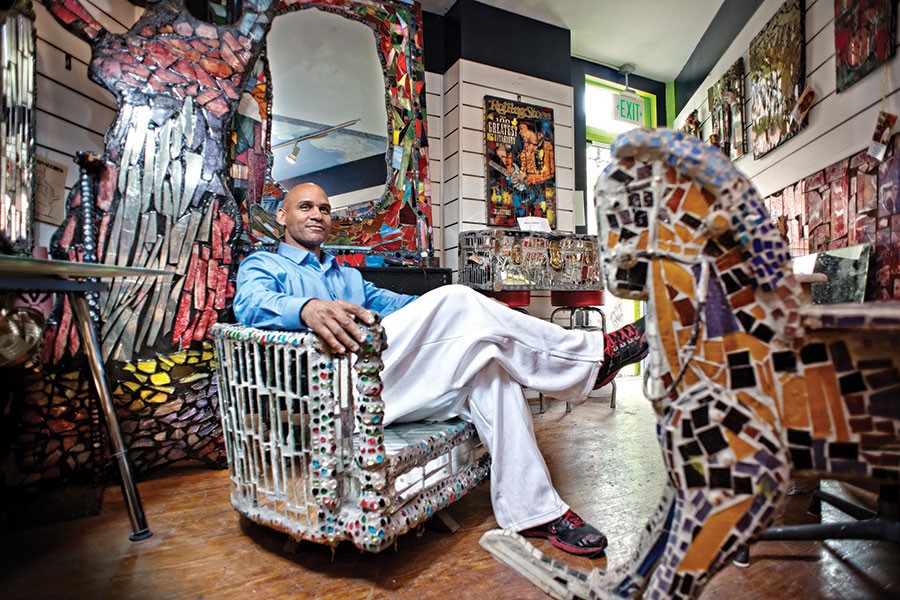

Artist Loring Cornish called a few days after an initial interview because he forgot to mention something. Over an afternoon conversation at his Fell's Point gallery and studio, the Baltimore artist had talked about his work process, his approach to materials, and how he first started the panels currently installed on the grounds of Johns Hopkins' Evergreen Museum & Library. These panels began as his exploration of the struggles of blacks and debuted in a 2009 exhibition at Morgan State University titled Pre-Inaugural America: Blacks and Jews Ascending and was expanded into the 2011 exhibition In Each Other's Shoes at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. Now 10 of these panels occupy the Evergreen grounds. One of them is a breathtaking collage of shoe soles. They're piled onto a flat panel and create an uneven surface, like a bas relief of people's walking feet.

Image caption: 'No Cell Phones Beyond This Point,' bathroom in Loring Cornish's gallery, 2013.

Image credit: Christopher Myers

"When I first saw [Cornish's] work, I immediately connected with it. I felt as if I knew it," says James Archer Abbott, director and curator of Evergreen, remembering his initial encounter with these pieces. "I grew up in the Midwest, a product of the Great Society and the New Frontier eras. I also knew that I wanted a selection of [Cornish's] work to honor Martin Luther King's [August 1963] March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. That was always the intention."

Abbott had the panels, which also allude to the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the civil rights era, installed on the expanse of lawn that runs from Charles Street to the mansion's front entrance; taking them in becomes a casual, aspirational stroll toward the shining house on the hill—a visually subtle way to connect Cornish's work to the former home of John Work Garrett, who served in the U.S. diplomatic corps from 1901 to 1922. "[Garrett] was an ambassador during that era of Wilsonian idealism, dedicated to the idea of a society free from segregation and alienation," Abbott says.

And Cornish had called to say how much he appreciated this interpretation of the work. "He took [the panels] to another level that I never imagined," Cornish says by phone of Abbott's Evergreen installation. "The way they're hung outside, like they're floating in air—they're freer, and it gave them a whole new life."

This praise might sound odd given that Evergreen's In Each Other's Shoes: The Art of Loring Cornish almost didn't happen. Costs limited the number of panels that could be included, and Cornish shared with local media his concerns about how that might impact the work's overall integrity. Now that the show is up, he sounds positively elated.

Sure, that could be smart politics in a community as small as Baltimore, but change is Cornish's constant. His materials—glass, shoes, old pianos, whatever he scrounges from around the city—are repurposed. He constantly works on and reworks his art, and pieces evolve over time. In fact, that shoe piece didn't even start out as a way to address the African-American experience. It became that when Cornish saw something in it that needed to come out. And what comes out of Cornish is an expression of his faith.

Loring Cornish has risen from unknown artist to local art star in the past decade. In 2003 he had returned to Baltimore after working as an actor in Los Angeles, settling in the Druid Hill Park area near where he grew up. While in California, a friend had taught him how to do mosaics with tile, and Cornish enthusiastically took to it. He covered his rental house in the Silver Lake neighborhood with mosaics, filling holes in the floor with Bible verses, covering walls with coins, and making crosses in the wall.

Devoting himself to making art was an act of faith. "When I get to heaven, I just want to say, God, I wanted to see where you would take me instead of where I know I can go on my own merits," Cornish says of his decision to quit acting and do art full time. "So I went home and started worshiping God and doing art and starved for a couple of years."

Finances forced him to leave Los Angeles, but the house caught the eyes of a neighbor who recognized the outpouring of a self-trained artist. A 2001 Los Angeles Times article wondered who the unknown artist behind it was, notoriety that Cornish didn't know about until he called a friend in L.A. just to catch up.

Cornish, however, hadn't stopped working after returning to Baltimore. He bought a house and covered it in glass, and then bought another and covered it, too. (Recently, one of his mirror-lined bathrooms was featured on the cable network TLC's Insane Bathrooms program.) Rebecca Hoffberger, founding director of the American Visionary Art Museum, took notice of his work and included pieces in AVAM's 2006 show Home & Beast. Other inquiries soon followed.

One was from Urban Outfitters, whose former store in the Inner Harbor had a large window for which it was seeking artwork. Cornish had something in mind. When he first got back to Baltimore, he had collected discarded shoes in a shopping cart. He wasn't sure what he was going to do with them, and one day he started cutting up all the blue shoes and gluing them to a panel. The resulting piece was a colorful collage of blue shoes and soles, like a Robert Rauschenberg combine, that hung in the store's window.

The piece eventually came back to his studio, and he decided he needed something simple, "because I had nothing in my gallery black and white," he says. "So I took that piece, and I covered it with mosaic glass—white squares. First I painted the shoes all black. Then put white squares on it. And then grouted it black."

Around the same time, Cornish was approached by Morgan State to mount a solo exhibition, and he felt it was time to do something thematic with his work. The struggle of black Americans came to mind, "as if that hadn't been done before," he says, laughing at his own presumptuousness. "And then I argued with myself, Well, you haven't done it before, so don't let that stop you."

Cornish says that immediacy guides his art-making process. Whatever's at hand is what gets used, and while he's gained certain skills over the years, he likes to remain open to chance. When he started working on the Morgan show, he found a collection of images of Martin Luther King Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, and John F. Kennedy in his basement, so he decided he'd use some of those.

"And things just started appearing before my eyes," he says. "I looked around at the work that I had done, and I looked at the piece that's black and white that's all shoes, and thought, 'Oh my gosh, that's the March on Washington.' All those shoes crumpled up together, a black and white issue, so to speak, and it was perfect. Everything just began to gel."

He's offering a cursory glance at his creative process. He amasses materials, an idea comes to him, he starts working—and then people come into his life that present opportunities to add richness, clarity, and depth to the work.

Cornish assumed he understood what the Morgan show was going to be about until he met local art collectors Ellen and Paul Saval, after which he decided he needed to tell the story of Jewish struggle alongside that of African-Americans—even though he knew nothing about Jewish history. He learned through the work, and he wants the work, and himself, to remain open to what he doesn't know and what he can't expect.

"I don't ever want to get to the point where I have a preconceived notion of what the end result is going to look like because then I'm not open to where the art really wants to go," Cornish says. "That's manufacturing. I'm not a manufacturer."

Instead, he allows the art to take him wherever it needs to. Cornish recently started what he calls his next museum show—although he doesn't know if a museum will want it, or what the work will look like, or what it's going to be about. He knows it will be an all-glass show with lights. Everything else, he'll figure out along the way.

"I have no idea how it's going to be lit, how it's going to hang, how it's going to look," Cornish says. "All I know right now is that I have the glass to do it. I'm right at the beginning stages—just as I was right at the beginning stages of the struggles for blacks. I had no idea where it was going to go, but I'm believing [in the work]. It'll go where it needs to go without any word from me. It doesn't need my input; all it needs is the energy from my body."

In Each Other's Shoes: The Art of Loring Cornish runs through Sept. 29 at Evergreen Museum & Library.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged visual art, evergreen museum